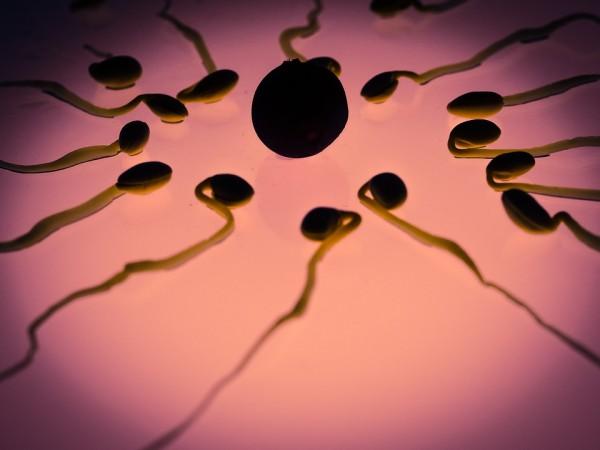

Eggs have always been portrayed as passive and sperm as active fighters, battling their way towards the egg. However, new research shows that the eggs aren't as passive as they are thought to be.

According to a study by researchers in Seattle, female's eggs can select sperm with the best genes and ensure the healthiest offspring possible. It also showed that semen does not appear to have the same ability as the eggs to detect good or bad genes.

Joe Nadeau, principal scientist at the Pacific Northwest Research Institute, believes eggs are an active player in reproduction. He has found examples that suggest fertilisation is not random, Quanta Magazine mentioned.

This research defies Mendel's Law that suggests fertilisation is random.

According to the Daily Mail, for the study, Professor Nadeau bred female mice carrying one normal and one mutant copy of a gene that increased the chance of getting testicular cancer.

On the other hand, male mice had normal genes. The offsprings produced followed Mendel's law -- there was a random dispersal of the mutated form among the offsprings.In the second experiment, Professor Nadeau reversed the breeding – the male mice had the mutant copy of the cancer gene and the females had normal ones.

It was found that only 27 percent of the offspring had a mutant variant as compared to 75 percent that they expected to see.

"Researchers found no evidence the mutated mice embryos were dying shortly after fertilisation, rather they were never fertilised," Daily Mail reported.

Though there's no evidence of how the eggs and sperm do this, Nadeau believes in two possibilities: 'The rate of metabolism of B vitamin, such folic acid - which is an important signalling molecule - is different in sperm and eggs.' And, these molecules play an important role in fertilisation.

Another hypothesis suggests that the sperm is in the female reproductive tracts before the egg is fully-formed.

"Female reproductive anatomy is more cryptic and difficult to study, but there's a growing recognition of the female role in fertilisation," said Mollie Manier, an evolutionary biologist at George Washington University.

"We've been blinded by our preconceptions. It's a different way to think about fertilisation with very different implications about the process of fertilisation," said Dr Nadeau.

Earlier this month, research was done using sea urchin populations off the Pacific coast of Canada. The paper published in the journal American Naturalist found that the eggs could choose their preferred mate from the crowd.

During the experiment, Dr Levitan 'induced male sea urchins to spawn' and then collected the seawater full of eggs in syringes. Then, tests were carried out on the eggs to find out how many different males' sperm were present.

Dr Levitan said: "While we expected to find that single eggs generally encounter sperm from a single male, we found that eggs are often simultaneously encountering sperm from more than one male in the brief interval between sperm contact and fertilisation."

He added: "This is the first evidence that sperm from different males compete for the same egg, which indicates an opportunity for eggs to have a choice."

Also, other research from the University of East Anglia in 2013 showed that female eggs choosing sperm is possible, as females coat their eggs with ovarian fluid that contains chemicals which attract a sperm with the right sort of genes.