The letter "G" has two lowercase versions and most people do not know this. The written form of the letter is wildly different from the print version and in spite of seeing it everywhere, few can recall it from memory, or accurately reproduce it by hand.

This was the basis of a research conducted by the Johns Hopkins University where scientists are studying the importance that writing plays in learning letters. Print version of the letter g is ubiquitous; most digital medium (including this one) use g differently from how people write it, or how they were taught to write it in school, according to a report put out by the University.

While most people do not seem to know that there are, in fact, two versions of the letter, fewer still can accurately pick it out in a lineup, the study found.

"We think that if we look at something enough, especially if we have to pay attention to its shape as we do during reading, then we would know what it looks like. But our results suggest that's not always the case," said Johns Hopkins cognitive scientist Michael McCloskey, the study's senior author.

"What we think may be happening here is that we learn the shapes of most letters in part because we have to write them in school. 'Looptail g' is something we're never taught to write, so we may not learn its shape as well."

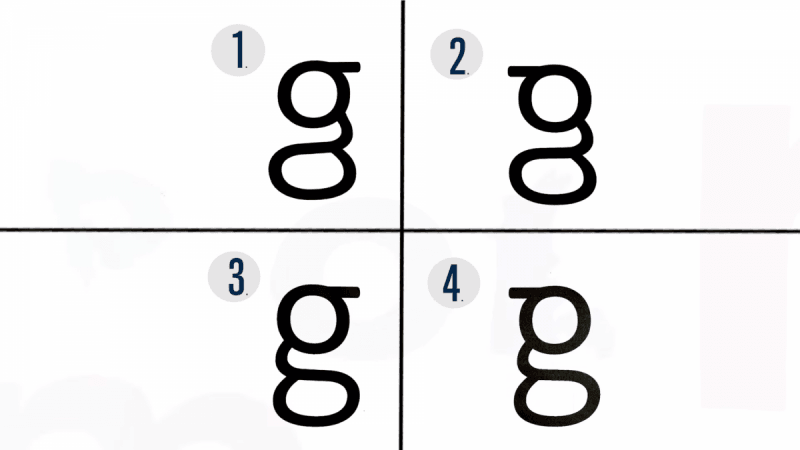

Like the letter "A" the letter "G" also has two lowercase versions, one is the –g the looptail– which is the version that is used by Calibri and Times New Roman, so it is this version that is seen everywhere. The other is the handwritten one that looks like a circle with a hook below it.

Researchers conducted three tests to see the level of awareness that people had about their Gs and if they knew the difference between the written and type letters.

The first test involved asking people if they knew the different letter that had more than one version of its lowercase. Of the 38 adults questioned, only two mentioned G and only one was able to write both forms correctly.

"We would say: 'There're two forms of g. Can you write them?' And people would look at us and just stare for a moment, because they had no idea," said first author Kimberly Wong, a junior undergraduate at Johns Hopkins. "Once you really nudged them on, insisting there are two types of g, some would still insist there is no second g."

The second test involved asking 16 different participants to read a paragraph that was printed out with looptail gs silently, but only words with g were supposed to be read out loud. Surprisingly, when asked to write out the gs that they had just only seconds read out loud and paid particular attention to, half of them wrote it wrong. They simply wrote the cursive, opentail g. While the other half wrote the correct type, only one wrote it correctly.

The final test involved 25 new participants to identify the right g in a lineup. Only seven were able to. "They don't entirely know what this letter looks like, even though they can read it," said co-author Gali Ellenblum, a graduate student in cognitive science. "This is not true of letters in general. What's going on here?"

When it is not written down, knowledge of letters really do seem to suffer, especially considering the fact that people are writing less and less.