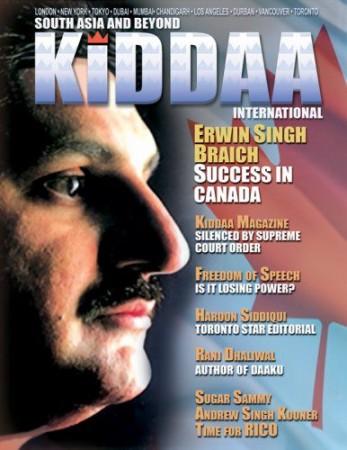

Erwin Singh Braich, the mysterious tycoon behind a $1.2-billion bid to rescue Yes Bank, says he is buying the bank for its name. He wouldn't have been interested had the name been 'No Bank'. Though he claims he is Canada's richest man but lives in a three-star motel in the prairies and has no headquarters. Not even a banker to manage his supposedly huge fortune, media reports suggest. His past is chequered with a history of lawsuits including a bankruptcy proceeding as well as soured international business deals.

Fourth largest lender

Braich has reportedly said that his rationale for investing in Yes Bank was simple: "I loved the logo and I had my people do the due diligence very deeply." He added: "If it was called 'No Bank,' I wouldn't have been interested."

Yes Bank desperately needs the cash injection to replenish its core equity capital

Braich, 63, the son of a lumber baron who had migrated from India's Punjab and set up a flourishing business in Canada, has sought a $2-billion preferential share sale, 60 per cent of which would be taken up by Braich and his partner, Hong Kong-based SPGP Holdings, a report on the Economic Times website said. A Bloomberg News reported on Monday that India's fourth-largest private lender is likely to reject the offer from Braich and SPGP, opting instead for institutional investors, according to a person familiar with the matter, the report said.

The Mumbai-based Yes Bank has been tottering from bad loans, including to some of the non-bank lenders caught up in India's shadow banking crisis. Yes Bank desperately needs the cash injection to replenish its core equity capital, which is about to dip below the 8 per cent regulatory minimum. The bank's stock has fallen 69 per cent this year, eroding its market value to Rs 14,300 crore ($2 billion). The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been closely monitoring the developments as it does not want a collapse and resultant crisis.

Braich has said he has the money for the investment and has provided enough documentation to Yes Bank's Chief Executive Officer Ravneet Gill. "I've been under the radar," the report quotes Braich as saying in a phone interview. "We have a lot of different holdings and assets that people don't know about." He said the funds would be in escrow by the time Yes Bank shareholders met to approve the offer.

However, there are plenty of signs from Braich's past raising scepticism. Official records available in Canada and the US show he had been mired in dozens of lawsuits with family members, creditors and business associates.

Two investors in the Democratic Republic of Congo sued him in 2008 after he proposed a plan to buy scrap metal claiming that he had a multimillion-dollar commodity trading business. The investors, Roger and Punit Menda, sued him and four others for defrauding them of $340,000, saying Braich lied about the metal contracts and "did not possess the personal wealth he claimed to and was, in fact, without any personal assets." Braich failed to respond to the complaint or appear in court, according to a default judgment ordering the money be repaid with interest.

The report cites Robin Phinney, former president of Canadian potash developer Karnalyte Resources Inc., who said he met Braich several times in 2015 when Braich said he was ready to fund a roughly $1.5-billion mining facility. The deal fell through after Braich allegedly jumped the gun with a news release that said his group was set to take control of Karnalyte. Braich says he had a binding bid with Karnalyte but "they screwed me" and allowed another investor from Gujarat, India to push him out.

Built a fortune

Braich grew up in Mission, British Columbia, 70km southeast of Vancouver, as the eldest of six children in a Sikh family. His father Herman was respected in the local Indo-Canadian community after he had left India at the age of 14. He built a fortune in British Columbia's forestry industry before he died in 1976.

"The reason I've had so much litigation was because I was a trustee for my father's estate," the report quotes Braich as saying. Those headaches include a 1999 involuntary bankruptcy he said was orchestrated by opponents, including his brother.