While the world has been dealing with the onslaught of the SARS-CoV-2 virus since 2019, another pandemic has plagued mankind for over 40 years: HIV/AIDS. Thanks to the advancements in medical science, individuals infected with HIV (human immunodeficiency viruses) can live reasonably normal lives. However, the virus cannot be completely eliminated from the body. Now, scientists have found that the lack of a crucial protein could be a reason behind the lingering of the pathogen despite treatment.

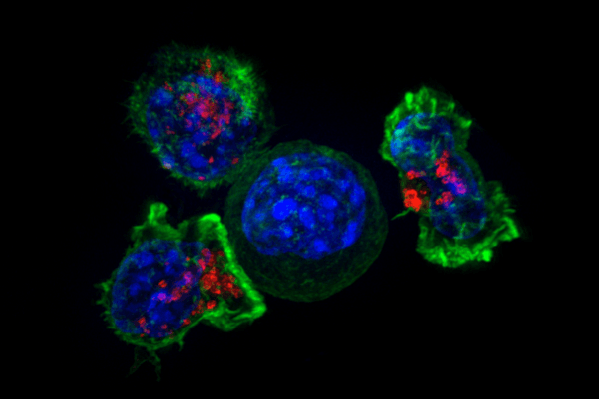

In a new study, researchers from the University of Alberta have discovered that the killer T-cells (CD8+ T cells)—a class of white blood cells—in the bodies of HIV patients have little or no presence of a key protein known as CD73. This could be the answer to the mystery of why the HIV virus cannot be fully eliminated from the bodies of infected individuals.

"This mechanism explains one potential reason for why HIV stays in human tissues forever. This provides us the opportunity to come up with potential new treatments that would help killer T-cells migrate better to gain access to the infected cells in different tissues," said Dr. Shokrollah Elahi, lead author of the study, in a statement. The findings were published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

A Four-Decade Pandemic

HIVs are retroviruses that target immune cells responsible for protecting the body from infections. Over time, the infection can result in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), where the immune system becomes weak. This leaves the body vulnerable to other infections and fatal diseases. According to the WHO, as of 2020, nearly 38 million people are living with HIV/AIDS worldwide, and 680,000 people died of HIV-related causes in 2020 alone.

Since the beginning of the pandemic in 1981, 36.3 million lave lost their lives. HIV can affect individuals of any age. It is transmitted through sexual contact, through contact with body fluids of an infected individual, or via other routes such as mother to fetus or blood transfusion. Unfortunately, a cure for the infection has remained elusive.

While antiretroviral therapy (ART) has enabled millions of HIV patients to live better lives and has increased their life spans, the virus cannot be eliminated from the body entirely. The pathogen survives in certain cells deep within several human tissues; staying hidden from the immune system.

Impairing Ability of Killer T-cells

CD8+ T cells are white blood cells that target and destroy virus-infected cells, cancer cells, and foreign cells.CD73 protein plays a crucial role in the migration and movement of cells into tissue. Through their analysis, the authors gleaned that in the absence of the protein, the ability of killer T cells to locate and neutralize HIV-infected cells is compromised.

After the role of CD73 was identified, the team shifted its focus to comprehending the likely reasons that lead to the drastic decrease in the protein's levels. It was learnt that chronic inflammation—which is common among HIV patients—was partly responsible for the reduction of CD73.

The authors discovered that this chronic inflammation leads to the increase in the levels of microRNAs, a category of non-coding RNAs that play a key role in the regulation of gene expression. "These are very small types of RNA that can bind to messenger RNAs to block them from making CD73 protein. We found this was causing the CD73 gene to be suppressed," illustrated Dr. Elahi.

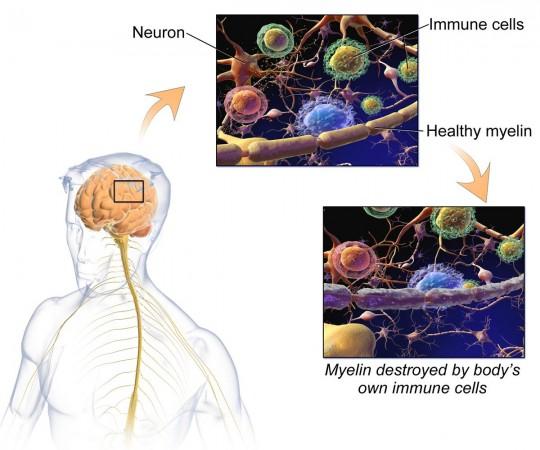

Potential Treatment for MS

In addition to potentially benefitting patients with HIV, the research could open new avenues into the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS). Older studies have found that HIV patients have a lower risk of developing MS. The findings of the current study help explain the reason behind this lowered threat.

"Our findings suggest that reduced or eliminated CD73 can be beneficial in HIV-infected individuals to protect them against MS. Therefore, targeting CD73 could be a novel potential therapeutic marker for MS patients," noted Dr. Elahi. He stated that the next step in the research is to identify ways in which the CD73 gene can be turned 'on' in HIV patients and 'off ' in those living with MS.