Using NASA's Mars Perseverance rover, a team of scientists including University of Florida astrobiologist Amy Williams has collected the first Martian rock samples that could be returned to Earth – the first step toward answering if the red planet ever hosted life.

The rock samples come from the floor of Jezero crater, which was chosen as the study site because it sports a large river delta that once flowed into an ancient lake. Scientists believe that a watery Mars could have supported life billions of years ago.

"These kinds of environments on Earth are places where life thrives. The goal of exploring the Jezero delta and crater is to look in these once-habitable environments for rocks that might contain evidence of ancient life," said Williams, a professor of geology at UF. Williams is one of the long-term planners for the Perseverance mission and helps decide where to send the rover and what tests and samples to prioritize.

The mission science team presented its findings from its exploration of the Jezero crater floor, including a description of the rock samples collected there, in Science on Aug. 25. The rover is now surveying the river delta to collect additional rock samples for the Mars Sample Return mission.

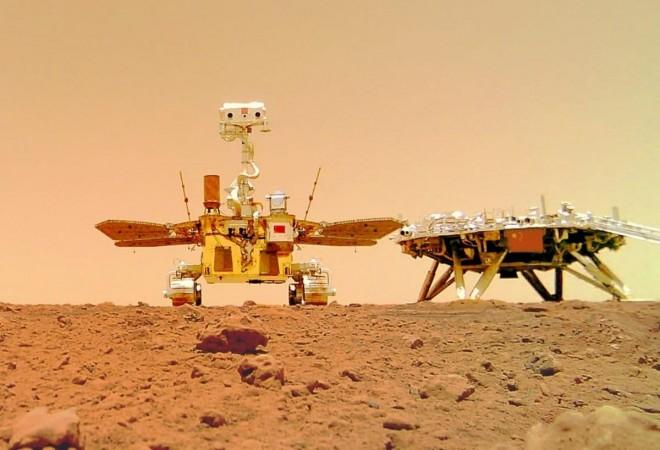

Led by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Perseverance landed at the bottom of the Jezero crater in February 2021. Since then, scientists have explored the geological makeup of the crater floor using a suite of tools on board the rover that can take pictures of and analyze the chemical composition of rocks, as well as see their structure in the subsurface.

The scientific team discovered that the crater floor had eroded more than they expected. The erosion exposed a crater made up of rocks formed from lava and magma, known as igneous rocks. The scientists originally expected that sedimentary lake or delta rocks would lay on top of these igneous rocks. It's likely that the softer sedimentary rocks wore away over eons, leaving the tougher igneous rocks behind.

The rocks the scientists analyzed and stored for return to earth have been altered by water, further evidence of a watery past on Mars.

"We have organisms on Earth that live in very similar kinds of rocks," Williams said. "And the aqueous alteration of the minerals has the potential to record biosignatures."

NASA and the European Space Agency are planning to return the rock samples to Earth around 2033. The ambitious plan requires building the first vehicle that can launch from the surface of Mars and rendezvous with an orbiter that ferries the samples back to Earth.

The payoff for that herculean task will be highly detailed studies of the rock samples that cannot be performed on the rover. These studies include measuring the age of the rocks and looking for signs of ancient life. Because the rock samples taken at the bottom of the crater likely predate the river delta, dating these rocks will provide important information about the age of the lake.

"I'm excited about what's coming next," said Williams.