![Women working at a site under MGNREGA [Representational image] MGNREGA workers](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/650080/mgnrega-workers.jpg?h=450&l=50&t=40)

The wage parity of millions of workers under MGNREGA seems to have gone for a toss with the Union Finance Ministry objecting to the proposal. Media reports quote the ministry as saying that such parity is not possible as it would involve an additional burden of Rs 3,000 crore to the central government.

It was not a surprise when the government did not accept the indexation method suggested by the Mahendra Dev Committee, which could have led to higher wages for labourers working under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Media outlets reported rural development secretary Amarjeet Sinha as saying that a committee set up under economist Mahendra Dev in 2013 had recommended one-time parity between MGNREGA wages and the consumer price index for agricultural labour (CPI-AL). The increase in wage rate has been meagre, as low as a rupee or two in some states.

Under this scheme, members from rural areas work in nearby villages as manual labourers at construction sites. The wages calculated in such areas are based on piece rate, which cannot be called a daily wage. This piece rate depends on the wage rate specified by the Centre and is revised every year.

This scheme has brought into discussion plenty of unanswered questions when it comes to fixing wage rate. Being a government employment scheme, can the government shy away from paying the minimum fixed wage? How will the wage rate affect the labour market? This again brings us back to factors affecting the local labour market that includes the number of days of employment in a year and when is it being made available.

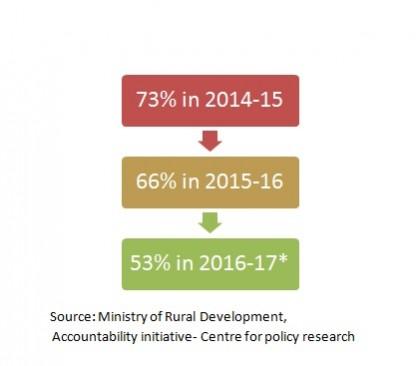

With the drought canvassing most parts of the country for the past three years, the status has remained grim. The agrarian crisis, due to varied factors, has slowed down farm incomes. The average number of employment days per household, which ideally promises full 100 days employment in a year, has been just between 40 and 50 days. With the decrease in the number of days of employment, the total number of households or labourers who have worked in a year has decreased in the past four years.

Even though the government claims "highest ever" budget allocation for the scheme, it has failed to appease the workers rights groups who still feel that the government has "hardly increased" the outlay in the past one year. The government expenditure was way ahead of its outlay. Payments which are pending from the previous financial year continue to carry the status of "being under consideration". Also, reports say that some other programmes under rural development are being funded through MGNREGA which include toilet and housing schemes. To sum up, the outlay continues to remain inadequate to meet real needs.

Can MGNREGA still qualify to be called a poverty alleviation initiative of the government? For the voiceless farmers who continue to earn a living from their farms and depend on this scheme during the non-monsoon periods, this scheme has done little good. Though wage rates might tend to increase the budget outlay, the government must at least provide a real hike in wages to fight increasing rural distress.

!['Had denied Housefull franchise as they wanted me to wear a bikini': Tia Bajpai on turning down bold scripts [Exclusive]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806605/had-denied-housefull-franchise-they-wanted-me-wear-bikini-tia-bajpai-turning-down-bold.png?w=220&h=138)