In a groundbreaking research that raises questions about the irreversible nature of death, US scientists revived light-sensing neuron cells in dead people's eyes and restored communication between them.

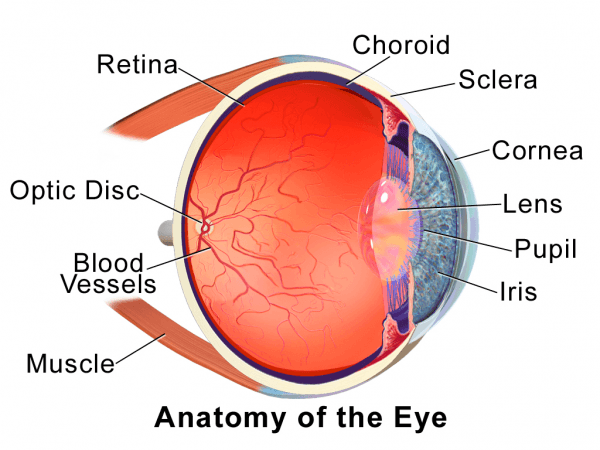

Billions of neurons in the central nervous system transmit sensory information as electrical signals. In the eye, the specialised neurons are known as photoreceptors that sense light.

According to the team from John A. Moran Eye Center at the University of Utah and Scripps Research, eyes from the donors responded to even dim light 'the way they do in the living eye'.

While initial experiments revived the photoreceptors, the cells appeared to have lost their ability to communicate with other cells in the retina. The team identified oxygen deprivation as the critical factor leading to this loss of communication.

In the paper published in the journal Nature, the team used the retina as a model of the central nervous system to investigate how neurons die - and new methods to revive them.

"We were able to wake up photoreceptor cells in the human macula, which is the part of the retina responsible for our central vision and our ability to see fine detail and colour," explains Moran Eye Center scientist Fatima Abbas, lead author.

"In eyes obtained up to five hours after an organ donor's death, these cells responded to bright light, coloured lights, and even very dim flashes of light."

In the study, the team procured organ donor eyes in under 20 minutes from the time of death, and then designed a special transportation unit to restore oxygenation and other nutrients to the organ donor eyes.

They also built a device to stimulate the retina and measure the electrical activity of its cells. With this approach, the team was able to restore a specific electrical signal seen in living eyes, the "b wave." It is the first b wave recording made from the central retina of postmortem human eyes.

The process demonstrated by the team could be used to study other neuronal tissues in the central nervous system. It is a transformative technical advance that can help researchers develop a better understanding of neurodegenerative diseases, including blinding retinal diseases such as age-related macular degeneration.

The study joins a body of science raising questions about the irreversible nature of death, partly defined by the irreversible loss of neuronal activity.

A study by Yale University researchers made headlines when they revived the disembodied brains of pigs four hours after death, but they did not restore global neuronal activity.

"We were able to make the retinal cells talk to each other, the way they do in the living eye, to mediate human vision," said Moran Eye Center scientist Frans Vinberg.

"Past studies have restored very limited electrical activity in organ donor eyes, but this has never been achieved in the macula, and never to the extent we have now demonstrated."