When it comes to mosquito-borne diseases, malaria is among the worst. It claims thousands of lives annually worldwide and is widely considered an infection of the blood and liver. Also, the antibodies produced in response to the disease are well documented. However, scientists have reported the detection of an unexpected antibody produced against malaria in infected individuals: one that is made primarily in response to infections of the mucous membranes of different organs.

Through a multi-institutional study, researchers discovered the production of IgA (Immunoglobulin A) antibodies—that are produced when the mucous membranes of organs such as the lungs are infected—in individuals infected with malaria. The study also found that the levels of IgA produced in children and adults in response to parasitic infection varied significantly.

"Not much had been done to study IgA antibodies in malaria infections, because people had not thought that they were important. Yet, because we were not looking for them, we may have missed a whole avenue of research that we can now explore," said Dr. Andrea Berry, corresponding author of the study, in a statement. The findings were published in the journal NPJ Vaccines.

A Deadly Disease

Malaria is caused in human beings by five parasitic protozoa from the Plasmodium family. They are transmitted through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes that serve as the primary vectors. Two of these protozoans—Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax—pose the biggest threats.

Several complications arise due to malaria. This includes damage to organs such as the kidneys and the liver, and can also result in the rupturing of the spleen. According to the World Malaria Report released by the WHO in 2020, there were 229 million cases of malaria in 2019. The estimated number of deaths due to malaria was approximately 409,000 in 2019. Children below the age of five accounted for 67 percent (274,000) of all malaria deaths.

Immune Response against Malaria

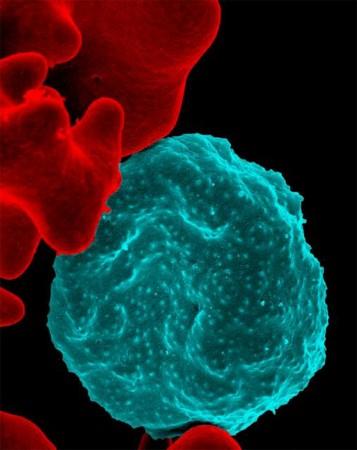

Different types of antibodies are produced by the immune system to help fight infections, and also to prevent reinfection. In older research, the authors had studied other antibody responses in patients with malaria. As expected, antibodies IgG (Immunoglobulin G), which is the most abundant antibody, and IgM (Immunoglobulin M), an antibody that appears during the initial phases of several infections, were detected.

However, they also chanced upon an unexpected antibody—IgA (Immunoglobulin A). This was uncharacteristic as these antibodies are mostly produced in response to infections in the mucous membranes in areas such as the intestines, lungs, and vagina, among others. Therefore, the researchers chose to conduct a follow-up study to investigate additional samples for confirming their discovery and to scrutinize more groups of participants.

Scrutinizing Antibody Responses

For the current study, the team examined antibody responses—both IgG and IgA—against P. falciparum in blood samples obtained from participants constituting three cohorts. The first group was composed of 32 individuals who had been infected through mosquito bites. Blood samples were collected on 1, 15, and 29 days post-infection.

The second group consisted of 22 volunteers who were challenged with the infection through direct intravenous (IV) introduction of P. falciparum. Blood samples were collected on 1, 29, and 57 days post-infection.

In addition to the two volunteer groups, the authors also collected samples from 47 children—between the ages of one to six—living in Mali, West Africa. These children were part of a malaria vaccine trial and their infections were naturally acquired during the course of the study.

Varied Levels of IgA

Through their analysis, the researchers learnt that adult participants infected with malaria had high levels of IgA antibodies. The vaccine trial group consisting of Malian children exhibited a reduced prevalence of IgA antibodies. They also showed variability in the antigen specificity. However, ten children from the cohort had IgA antibody levels that were similar to those observed in adult participants.

The team also noted that patterns of IgG response were different between the three groups. Nevertheless, despite these variations, IgG antibodies were found to increase among all three cohorts. One question, however, remains to be answered: What leads to the development of IgA antibodies in malaria patients?

"We do not know what triggers the IgA antibodies to develop, but we think it happens early in a malaria infection. Some people think that the response might happen when the mosquito injects the parasite into the skin. Interestingly, some of our participants were not bitten by mosquitoes because their malaria infection was delivered intravenously, so there are probably additional triggers for IgA development," stated Dr. Berry.

Understanding Cause of Variability

It is not certain why the levels of IgA in children were not universally high. Dr. Berry averred that several reasons could be responsible for the differing levels of IgA. "Perhaps, children's immune systems respond differently to the parasite than adults do, or it is possible that IgA antibodies are only created during the first malaria infection," she posited.

Deliberating on other potential reasons, Dr. Berry explained that the team was aware that the adult participants had received their first infection. However, it was not known whether the children in the vaccination trial had been infected previously.

While the timing of the infections and collection of samples among the adult volunteers was uniform, it was not the case among the child cohort. This was because their malaria infections occurred coincidentally during the course of the study.

Dr. Berry added that tests can now be carried out to ascertain whether IgA antibodies prevent malaria parasites from entering red blood cells or the liver. She also said that the proteins which are targeted by IgA antibodies can be investigated and it can be gleaned whether they can be used in vaccines.