While mankind aspires set to foot on Mars, the harsh conditions of space are likely to make the long journey to the red planet a difficult one for the human body. However, a new study states that understanding the tiny zebrafish's process of hibernation may provide potential insights into helping humans be protected from the elements of space, especially radiations, during space flight.

The study led by researchers from Queen's University Belfast demonstrated that when zebrafish are exposed to radiation, they are protected from it due to a hibernating process known as induced torpor. Deeper knowledge of the process, according to the authors, can help humans during space travel.

"We set out to determine if induced torpor is a viable countermeasure to the harmful effects of spaceflight. If humans could replicate a similar model of hibernation we have observed in the zebrafish, it could increase our chances of making humans a spacefaring species," said Prof. Gary Hardiman, senior author of the study, in a statement.

Lesser the Better

Hibernation is a commonly observed physiological process in nature. It is a state where an organism enters metabolic depression (reduced metabolism) and engages in very minimal or no physical activity. The mechanism enables several organisms to survive adverse conditions such as low environmental temperatures and scarcity of food.

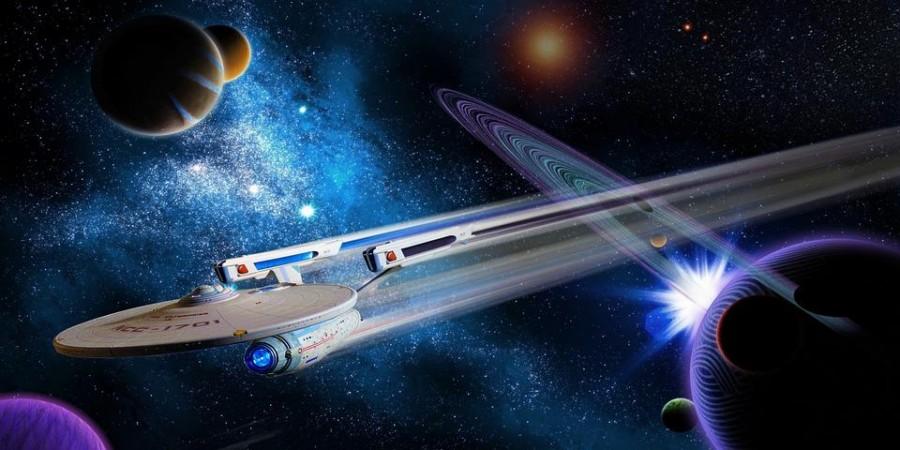

Most Hollywood sci-fi movies involving space travel often depict astronauts in a state of hibernation or stasis, and for good reason. Scientists believe that if humans can replicate the process of hibernation during space travel, it can help protect astronauts against the physical strains of space flight such as advanced aging and vascular problems, bone and muscle wastage, and radiation exposure.

Torpor, a form of hibernation, is a brief spell of suspended animation. It usually lasts less than a day. When in torpor, an animal's metabolism, heartbeat, breathing, and body temperature are greatly reduced. Studies in squirrels have proven that torpor extends the survival times of irradiated squirrels when compared to active controls. Through the current study, the authors aimed to prove that inducing torpor can benefit human beings while traveling in space.

Making Zebrafish Hibernate

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a freshwater fish that is native to South Asia. It is a popular choice in aquariums. Notably, it is also widely preferred as a vertebrate model organism for scientific research. They have been used by NASA researchers for a better part of this decade in similar experiments in space.

For the study, the authors exposed zebrafish to levels of radiation that an astronaut would potentially experience on a six-month journey to Mars. They observed that the radiation led to signatures of oxidative stress (imbalance between antioxidants and free radicals), signaling of stress hormones, and impeding of the cell cycle within the zebrafish.

Next, the team used melatonin treatment and reduced temperature to induce a torpor-like state in a second group of zebrafish and exposed them to the same levels of radiation. Following this, the fishes' patterns of gene expression were examined in order to analyze protective effects in this induced state of mental and physical inactivity.

Protection during Space Fight

Interestingly, the induced torpor was found to lower the metabolic rate within the zebrafish. It led to the creation of a radioprotective effect in the fishes and protected them against the lethal effects of the radiation they were exposed to. "Our results reveal that whilst in induced torpor, the zebrafish showed that a reduction in metabolism and oxygen concentration in cells promotes less oxidative stress and greater resistance to radiation," said Thomas Cahill, co-first author of the study.

According to Prof. Hardiman, if torpor could be induced in human beings, it would result in diminished brain function. This would lead to the reduction of psychological stress. A change in their metabolism would eliminate the requirement for food, water, or oxygen. Also, there may be a possibility of the process protecting muscles from wastage brought on by the effects of microgravity and radiation.

"These insights into how a reduction in metabolic rate can offer protection from radiation exposure and could help humans achieve a similar kind of hibernation, counter measuring the damage they currently face during spaceflight," concluded Cahill.