When it comes to respiratory infections, viruses and bacteria are often looked at as primary causes. However, fungi can give rise to such infections as well, and Cryptococcus neoformans is one such example. Its inadvertent inhalation can cause lung infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Now, scientists have discovered that the fungus shrinks in size in order to acquire the ability to infect the brain.

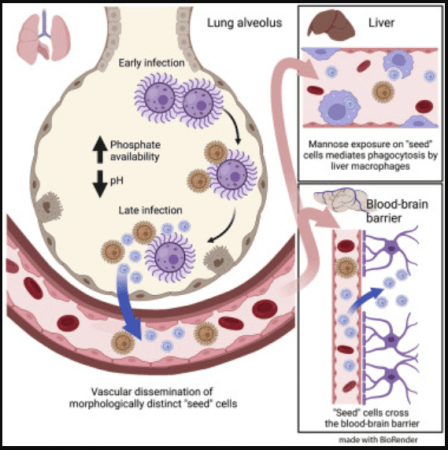

Through a new study, researchers from the University of Utah Health have found that C. neoformans cells transform into smaller "seed" cells that develop the capacity to travel to the brain and infect it. The animal study also suggests that a chemical compound—phosphate—could be the trigger behind this remarkable change in size and infectivity. These findings, which were published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, could aid in the development of new strategies to tackle infections caused by C. neoformans.

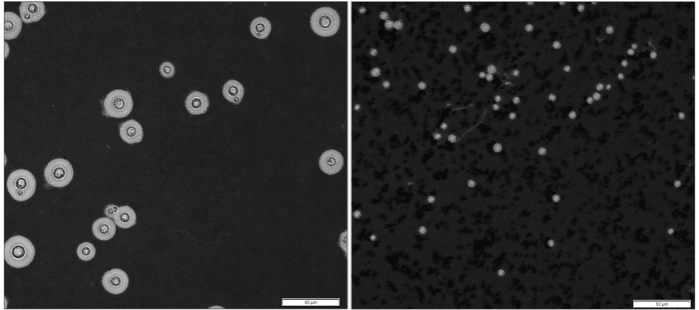

"Cryptococcus cells in the lungs are very diverse with different sizes and different appearances. So, when my graduate student showed me pictures of the uniformity of cells from the brain, I was shocked. It suggested that there was some very strong reason why only this population of cells were making it that far into the body," said Dr. Jessica Brown, senior author of the study, in a statement.

Adapting to Survive

C. neoformans is a yeast, a member of the fungi family, that is found naturally across habitats. From soil to animal droppings to rotting wood, it can survive in any environment. When the fungus is accidentally inhaled, it can enter and survive in the respiratory system: the site of most of the infections (such as pulmonary cryptococcosis) caused by it. However, C. neoformans can also cause other lethal infections such as encephalitis and fungal meningitis, particularly as a secondary infection in AIDS patients.

From the lungs, the fungus can travel to other vital organs of the body such as the brain—that have their own unique microenvironments—through the bloodstream and infect them. Previous studies have found that C. neoformans grows to 10 times its normal size in order to survive within the lungs. Researchers posit that this increase in the pathogen's size may render its destruction by the immune system difficult.

Surprisingly, the size of C. neoformans cells in other parts of the body has been found to be significantly smaller. It is this difference in size that intrigued Dr. Brown. She wanted to ascertain whether the diminished size of the fungal cells provided them with any advantages and if it assisted them in colonising organs such as the brain.

Transforming into 'Seed' Cells

For the study, the researchers used different sizes of C. neoformans to infect mice. It was learnt that in comparison to large and medium-sized fungal cells, the smallest preferred infecting the brain. Not only were these cells minuscule (compared to large and medium cells) but they were different as well. When compared to larger C. neoformans cells, their smaller counterparts possessed unique characteristics on their surface that were crucial in gaining access to the brain. In addition, the tinier cells also activated a separate set of genes.

Based on the findings, the team suggests that these small C. neoformans cells, dubbed "seed" cells, are more than just diminutive forms of bigger cells. Rather, they have transformed extensively. Following their investigation for triggers that give rise to these changes, the authors found that a particular chemical could induce the switch—phosphate.

It is known that when tissues are damaged during an infection, phosphate is released. Dr. Brown noted that this occurs in the lungs—the area that fungus inhibits first after entering the body—when there is an infection, leading to the accumulation of phosphate. This enables the C. neoformans cells to transform themselves into seed cells and grants them the ability to proliferate to other organs.

Bird Droppings: Source of Lethality?

According to the team, C. neoformans' ability to target the brain efficiently may have emerged from an unusual source: bird excrement (or bird guano). The fungus thrives in pigeon droppings. This excrement contains high levels of phosphate—the molecule that can trigger seed cells. Through further study, the researchers discovered that these droppings encourage the transformation of C. neoformans cells into their smaller and distinct forms.

Dr. Brown opined that this could illustrate how the pathogenicity of fungus may have originated. "We think that selective pressures from environmental niches like pigeon guano are somehow able to confer to C. neoformans the ability to infect mammals," she added.

While the tracing the potential origin of the fungus' pathogenic ability is fascinating, the team's immediate goal is to impede its capacity to infect through the use approved drugs in existence. The scientists are working towards discerning whether any of the existing FDA-approved compounds can prevent C. neoformans from turning into seed cells. This could serve as a potential option for treating or even preventing damaging diseases caused by the fungus.