When Jane Nolmongen's husband banished her from their family home in northern Kenya after discovering she had been raped by a British soldier, she went somewhere she knew she would be safe: a village entirely run by women, where men are not allowed.

For the past 30 years, Nolmongen has lived in Umoja village in Samburu County, supporting her eight children and working land she could soon own, in defiance of a culture in which women are considered the property of their fathers and husbands.

"The village has been a source of support for me, because we have worked together to make progress in our lives and teach each other the importance of women's rights," said Nolmongen, 52, as she lit a fire to make some tea.

"Among the Samburu, we, as women, are just like rubbish to our husbands," she said.

Nolmongen was among the first residents of Umoja, which was founded in 1990 as a refuge for Samburu women who have suffered sexual assault and been cast out and stripped of any claims to their property or children, as well as those fleeing child marriage or female genital mutilation (FGM).

Today, the women are on the brink of being granted the title deed to a tract of grazing land by the county government – a right they never would have had outside the village – and are motivating nearby communities to also start giving land rights to women.

"In (Samburu) community, that was not possible for a woman 30 years ago. She would not be allowed to own land and other property because the husband would not allow her," Nolmongen said.

Umoja was created by Rebecca Lolosoli, who was thrown out of her community and beaten by a group of men for speaking out against the practice of FGM.

While recovering in hospital, she came up with the idea to start a village where men were banned.

Umoja, which means 'unity' in Swahili, started with 15 women – at its peak, the population grew to about 50 families, explained Nolmongen.

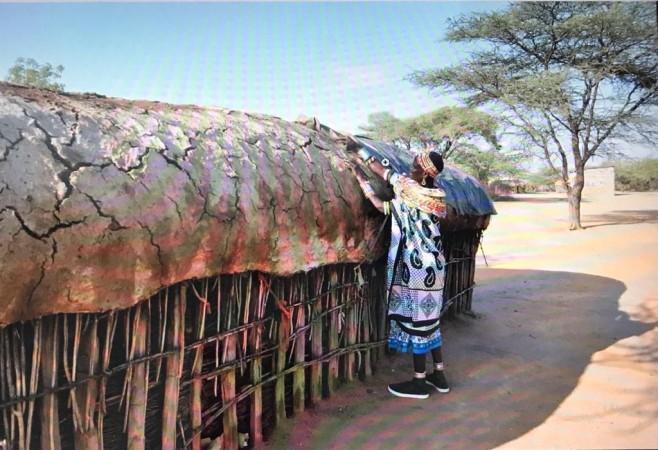

Now there are a total of 37 women and their children living in the village, which is made up of homes the women have constructed for each other and a school, all surrounded by a fence of thorny branches.

The women make money selling honey and handmade beads to tourists, although travel restrictions to curb the coronavirus pandemic mean they currently have no income, Nolmongen noted.

"After this disease came, (tourists) no longer come, and we have to think of other ways to survive," she said. "If someone has savings, that is what they use now until we can sell the beads again."

Henry Lenayasa, chief of the administrative region where Umoja village is located, said the women's move to register their land is an example of a growing recognition of equal property rights among the Samburu.

"We, as administrators, are guided by the constitution to ensure women get their fair share. I normally hold barazas (meetings) in various villages to ensure this message reaches them, and also emphasize the need to empower girls," he said.

COMMUNITY OWNERSHIP

Kenya's constitution states that all women have equal rights to own property, but in reality land is most often customarily passed from fathers to their sons, making it hard for women to own land.

Women own less than 2% of all titled land in Kenya, according to the Kenya Land Alliance, an advocacy network.

The Samburu practice communal tenure, with all decisions on how land is used and allocated made by men.

But soon the women of Umoja could have legal control over their own tract of grazing land, a few kilometres from the village, which they bought a few years ago with savings and donations.

The government is currently considering their application for a community title for the land, which is due to be partitioned.

If granted, the land title would help protect the women and their livelihoods from clashes over land and water that frequently break out between the Samburu and rival communities.

A spokesman for the Samburu County Lands Office could not be reached for comment.

SPREADING THE WORD

The women of Umoja also travel to nearby communities to teach people about the importance of including women in land and property ownership.

And whenever a woman leaves the village to return to her husband, the others make sure she does not revert to second-class status, Nolmongen said.

"We step in and teach her about (her rights) and even follow up to ensure that she actually gets to enjoy these rights, including seeing whether she is dressed well and has ownership of some property," she said.

In the neighbouring village of Nashami, Samuel Leyapem, 75, said over the past three decades the women of Umoja have inspired his community to grant women more of the rights they are entitled to.

"Nowadays, even us here in our village allow women to own property such as cattle and even buy land," he said, as he sat in the shade outside his home.

"But personally, I would like it more if, after the woman buys (land), she involves her husband, so that they are both happy."

Juliana Nnoko-Mewanu, a researcher on women and land for advocacy group Human Rights Watch, said women should not feel they have to cut men out of their lives to be able to make decisions on their property.

"Women must not resort to women-only spaces to experience the ability to access, use, control and benefit from land and perceive tenure security," she said over the phone.

"The government should institute safeguards to protect women's rights to property during marriage, divorce and in the case of the death of a spouse."

At Umoja village, Nolmongen is grateful that even though she never went back to her husband, she has been able to send all of her children to school and have agency over the land she lives and works on.

It is a right she has instilled in her grown children: one son who is in the police force and a daughter working as a journalist.

"They are now enlightened and can own property any way they want," she said.