The Sun has spewed a gigantic plasma wave into Mercury.

The plasma wave that stormed Mercury on April 12 is likely to trigger a geomagnetic storm and scouring material from the planet's surface, Live Science reported.

The sun's activity has been increasing far faster than scientists forecasted.

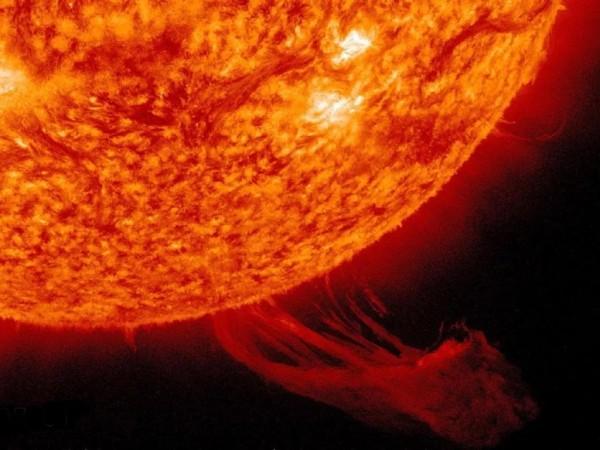

The powerful eruption, known as a coronal mass ejection (CME), was seen emanating from the sun's far side on the evening of April 11 and took less than a day to strike Mercury which is the closest planet to our star, according to spaceweather.com.

The storm may have created a temporary atmosphere and even added material to Mercury's comet-like tail, the report said.

The plasma wave came from a sunspot - areas on the outside of the sun where powerful magnetic fields, created by the flow of electric charges, get knotted up before suddenly snapping.

The energy from this snapping process is released in the form of radiation bursts called solar flares or as waves of plasma (CMEs).

On planets that have strong magnetic fields, like Earth, CMEs are absorbed and trigger powerful geomagnetic storms.

But unlike Earth, Mercury doesn't have a very strong magnetic field.

The atoms that are on Mercury are constantly being lost to space, forming a comet-like tail of ejected material behind the planet.

But the solar wind -- the constant stream of charged particles, nuclei of elements such as helium, carbon, nitrogen, neon and magnesium from the sun -- and tidal waves of particles from CMEs constantly replenish Mercury's tiny quantities of atoms, giving it a fluctuating, thin layer of atmosphere, Live Science reported.

Previously, scientists were unsure if Mercury's magnetic field was strong enough to induce geomagnetic storms.

However, two recent studies published in the journals Nature Communications and Science China Technological Sciences in February have proved that the magnetic field is, indeed, strong enough.

The first paper showed that Mercury has a ring current, a doughnut-shaped stream of charged particles flowing around a field line between the planet's poles, and the second paper pointed to this ring current being capable of triggering geomagnetic storms, the report said.

"The processes are quite similar to here on Earth," Hui Zhang, a co-author of both studies and a space physics professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute, said in a statement. "The main differences are the size of the planet and Mercury has a weak magnetic field and virtually no atmosphere."

Meanwhile, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center, the Sun's activity has also been increasing far faster than past official forecasts predicted.

The Sun moves between highs and lows of activity across a rough 11-year cycle, but because the mechanism that drives this solar cycle isn't well understood, it's challenging for scientists to predict its exact length and strength.