The real estate market has been moving rapidly towards a high inventory-low growth scenario following the brief demand uptick in late 2015 and mid-2016. Apparently, finding a real estate agent is easier than throwing back two shots of your favourite Scotch in an urban bar, though a prospective residential buyer would likely root for the second option. And, it's not all about demonetisation alone crippling demand.

The RBI had long believed that the American model of rate cuts spurring credit growth would work in India. But successive interest rate cuts since June 2016 have not led to the kind of consumer spending spurt which real estate companies would find appealing.

Housing loan uptake has fallen, and real estate companies have reported surplus inventories which might take years to clear off. Many who invested their unaccounted wealth in real estate are chomping on their losses as their projects languish half-complete, while prices of many finished projects have fallen an average 25-30 percent across the country.

That could partly explain the BSE Sensex breaching 32,000 levels, and the Nifty approaching the 10,000 mark on Monday, as high net worth individuals are getting comfortable with investing in "safer" assets like the stock market, either directly or through the mutual fund route.

The unmaking of policy

Much of the black money which demonetisation targeted is understood to be safely stashed away within bank lockers or invested in real estate since 2011, as well as high-yielding money market instruments post the 2008 worldwide economic crash. This conclusion is inevitable. What were they demonetising, really?

The RBI Weekly Statistical Supplement of June 9, 2017, reports that currency notes declined from Rs 17.9 lakh crore on November 8, 2016, to Rs 14.7 lakh crore on June 2, 2017.

During the same period, total deposits of scheduled commercial banks with the RBI and under the market stabilisation scheme increased by Rs 2.31 lakh crore and Rs 0.947 lakh crore, a total of Rs 3.25 lakh crore on account of deposits of demonetised bank notes. If these two figures are added: Rs 14.7 lakh crore and Rs 3.25 lakh crore, this would total Rs 17.95 lakh crore as against Rs 17.9 lakh crore on November 8, 2016. That's why it looks like all the demonetised currency has come back into the system.

This simple reading of currency circulation dynamics appears to have rattled the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). Call it sheer coincidence or plain logistical issues that RBI, for the first time, has not disclosed figures of notes in circulation for the week and fortnight ended June 30, 2017, the day it closes its annual accounts.

Where does that leave real estate, specifically the star residential housing segment, with all that "black money" roiling its veins down the years? Untraceable? Or, did the unaccounted wealth powering India's property prices skyward find safer havens in stocks, equity funds and the low-yielding bond market?

In fact, real returns from property, especially investments in housing projects, have been negative since June 2013, if we take other expenses like property tax, maintenance charges, interest paid on home loans -- after adjusting for tax benefit and inflation, among others -- into account.

Real estate data and analytics platform PropEquity's stats are diverting, though altogether not unforeseen. Housing sales fell by 41 per cent during the January-May period of 2017 at 1.10 lakh units across 42 major cities as property demand continued to be sluggish post demonetisation, according to PropEquity.

Housing sales stood at 1.87 lakh units during the year-ago period, as the market continues to be slow post-demonetisation.

Private equity (PE) players may still not buy into the realty gloom story. PE funds have put in $2.5 billion across 29 deals in real estate in the first half (H1) of 2017, which is 61 per cent higher than the corresponding period of 2016, according to data collated by Venture Intelligence. That points to robust optimism ruling the residential market. But there is a catch. Only half of the deals closed in H1 are residential and the rest are commercial, unlike two years ago, when 100 per cent of the deals were residential.

About 90 per cent of the PE money is being used to buy ready commercial properties and the rest for development of properties. Do we smell another bubble in the making if rentals fail to accurately measure up to asset prices? It's too early to take a call on that just yet; for as of now, the commercial property market has recovered and vacancy levels are at an all-time low.

The real worry is that demand in the residential market continues to sputter in the face of a barrage of new project launches.

Boomtown redux

Stymied by a multi-year slowdown, new home launches fell 62 per cent to 70,450 units during the first five months of this year as against 1,85,820 units in the corresponding period of the previous year, according to PropEquity.

The slowdown has led to significant delays in projects execution forcing buyers to protest and file cases against developers in courts. The housing sector has been further affected post-demonetisation. The implementation of the Real Estate (Regulation and Development Act), is expected to reduce delays in project deliveries as developers rush to complete previously launched projects to avoid penalties. But there are still few incentives for the genuine home buyer.

The tax benefit angle does not work anymore if buying a home for the sole purpose of tax gains is an objective. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley had in his Budget speech, limited all such deductions to Rs 2 lakh. That effectively kills a market created solely for the purpose of hyperventilating the benefits of tax deductions on self-owned or loan-backed homes and undermines an entire loan marketing universe and banker spiel underpinning such a market.

Jaitley's curtailment of incentives on home loans could have had a sobering effect on housing demand, though not as much in helping the market scale down prices. And, they do no favour to residential projects currently in the act of being launched.

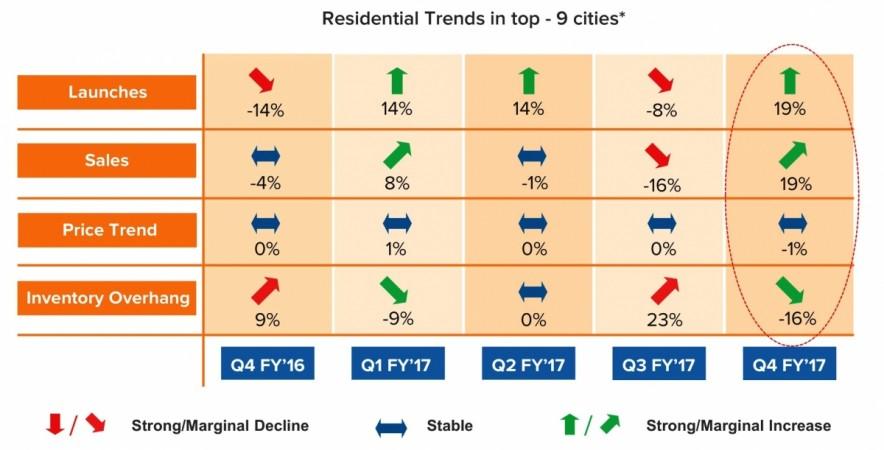

As pointed out earlier, the supply of homes has increased with new project launches happening across the top 9 cities, but prices haven't really dropped enough to match supply.

Market rumours indicate that banks could be playing some role in prices staying put at high levels or not falling enough to make new homes affordable in the top 9 cities. High default rates among the real estate, construction and supplier firms, who finance and implement their projects on bank loans, are not uncommon. Falling customer investments are not helping sustain the real estate sector, while banks are keen to recover their loans at the higher interest rates at which they lent them to real estate firms. Restructuring real estate corporate debt has always been a valuation nightmare for banks. Consequently, the idea of real estate companies reducing prices of new homes is anathema to the banks, and pressure from banks could be keeping prices steady.

So, what would it take to achieve a deviation from this normal? A price correction in the residential real estate sector would be dependent on a perfect storm of not just lower interest rates, but lower acquisition costs (read lower property prices), a degree of residential housing shortage, higher capital growth, higher rentals as an index of asset value, and higher credit growth as well. Impossibly difficult? Or simply, unreal estate? Perfect storms are called perfect storms for a reason.