A research team studying tiny particles found in Antarctica have uncovered evidence of an asteroid impact in Antarctica 430,000 years ago, using chemical clues locked in the particles to piece together what happened then.

The findings reiterate the need for the identification of these events in deep sea sediment cores and, if plume expansion reaches landmasses, the sedimentary record, said the team of scientists.

"We know asteroids are dangerous, and recent studies have suggested that airbursts are more dangerous than large asteroids, because larger asteroids are very rare," says Matthias van Ginneken, a planetary scientist at the University of Kent and lead author of the study.

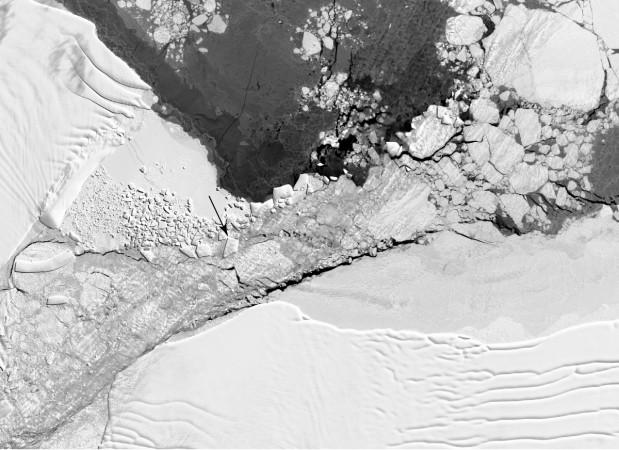

Published in journal Science advances, the new study described the ancient explosion in extra-terrestrial particles recovered on the summit of Walnumfjellet (WN) within the Sor Rondane Mountains, Queen Maud Land, East Antarctica.

They indicate an unusual touchdown event where a jet of melted and vaporised meteoritic material resulting from the atmospheric entry of an asteroid at least 100 metres in size reached the surface at high velocity, said the study.

Single-asteroid impact

This type of explosion caused by a single-asteroid impact is described as intermediate, as it is larger than an airburst, but smaller than an impact cratering event. The chondritic bulk major, trace element chemistry and high nickel content of the debris demonstrate the extra-terrestrial nature of the recovered particles, said the study.

Their unique oxygen isotopic signatures indicate that they interacted with oxygen derived from the Antarctic ice sheet during their formation in the impact plume. The findings indicate an impact much more hazardous that the Tunguska and Chelyabinsk events over Russia in 1908 and 2013, respectively.

This research guides an important discovery for the geological record where evidence of such events in scarce. This is primarily due to the difficult in identifying and characterising impact particles.

Medium-sized asteroids

The study highlights the importance of reassessing the threat of medium-sized asteroids, as it likely that similar touchdown events will produce similar particles. Such an event would be entirely destructive over a large area, corresponding to the area of interaction between the hot jet and the ground.

"To complete Earth's asteroid impact record, we recommend that future studies should focus on the identification of similar events on different targets, such as rocky or shallow oceanic basements, as the Antarctic ice sheet only covers nine per cent of Earth's land surface," said Matthias van Ginneken from the University of Kent in Britain.