Before the abrogation of Article 370, several Political leaders for years ran concerted campaigns demanding the revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir. They argued that Article 370 was hindering progressive central legislations from being extended to the erstwhile state. The reality is that central legislations were being applied to Jammu and Kashmir long before Art. 370 was repealed and the region bifurcated into Union Territories.

Central laws such as the National Food Security Act (NFSA) also called Right to Food, the MG-NREGA, and many other laws were extended to Jammu and Kashmir even when Article 370 was untouched and intact. Even controversial laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA), the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, 1958 (AFSPA), the Disturbed Areas Act, 1976 (DAA), and other laws were in effect in Jammu and Kashmir. The PDP-BJP alliance government, whose term lasted from April 2016 to June 2018, had even extended the new Goods and Services Tax [implemented in 2017] to Jammu and Kashmir.

It is the BJP that had held the charge of the state forest department in that coalition government, and yet it never extended the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, to Jammu and Kashmir.

Nor did the previous state governments enact state legislation on the pattern of this law, which is popularly known as the FRA.

Along with dozens of other central laws, the FRA was extended to Jammu and Kashmir only on 31 October 2019. This was done by the first order issued in connection with the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019.

Were the government of India really sincere about giving people of the former state their entitlements under the FRA, it would have rolled out this law long ago. In fact, even months after the reorganisation act was passed in 2019, there is still no sign that the FRA will be properly implemented in Jammu and Kashmir.

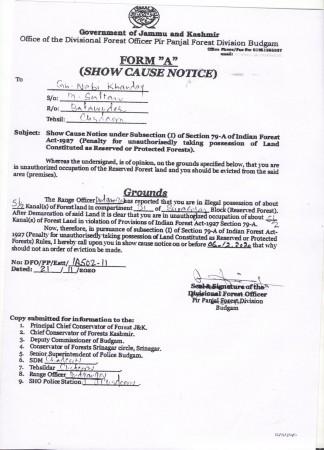

Notices issued to Tribals

Until November 2020, neither the Centre nor the Union Territory administration said a word about the Forest Rights Act (FRA). Then, starting in mid-November, the government invoked the 94-year-old obsolete and outdated Indian Forest Act, 1927, and began issuing eviction notices to Gujjar tribals and other traditional forest-dwellers. Some Gujjar huts (Kothas) in villages that are close to forests were also demolished.

The 1927 law contradicts the FRA, and people also resisted being evicted in some places. After a hue and cry, the evictions became a political issue and former chief minister Mehbooba Mufti visited some affected villages.

Still, rather shockingly, notices were issued in mid-November to tribals and traditional forest dwellers residing in the upper reaches of Budgam, where I live. The families being evicted have lived here for generations. Forest officials, on the orders of the local Divisional Forest Officer (DFO), even axed a huge number of apple and other non-fruit-bearing trees in a few villages allege locals. On 18 November, more than 10,000 apple trees were felled in Kanidajan village, and orchardists were issued notices only after the vandalism.

The forest department has asked tribal Gujjars and other traditional forest-dwellers to surrender the forest land they have been living on for centuries. We held public demonstrations outside the offices of the District Magistrate and DFO, Budgam. I wrote articles and shared many videos as well. The national and international press highlighted peoples' concerns too.

Finally, the Chief Secretary asked the authorities to start rolling out the FRA in Jammu and Kashmir. This process began mid-December 2020, but the way it is being implemented is making residents feel humiliated. Government officials such as panchayat secretaries and members of panchayat committees are resorting to undemocratic methods—also because there are vested interests involved—which is defeating the very purpose of the crucial FRA.

Awareness by Forest Officers?

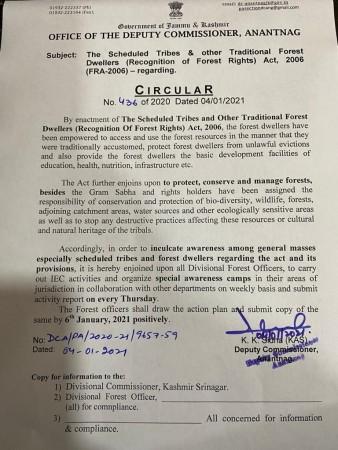

One mistake that many states committed when they implemented the FRA is now being repeated in Jammu and Kashmir. On 4 January, the Deputy Commissioner, Anantnag, issued a circular asking forest officers to create awareness of the FRA. However, the forest department is a "respondent agency" in the implementation of the FRA. In other words, can a body that holds the title to this land be expected to give, to tribals or traditional forest dwellers, the rights to this land?

To ensure that the FRA is implemented fairly and there is no injustice, nationally, it is the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs that has been made nodal agency. Similarly, in states and Union Territories, it is the departments of tribal affairs that are nodal departments to implement this law.

But in Jammu and Kashmir, the government seems to be ignoring the tribal affairs department and instead of giving forest officials charge of implementing this law. If this is a deliberate step, it needs to be questioned. If it is a result of their ignorance, it needs to be rectified.

It is unwise to call upon DFOs to carry out information, education and communication programmes among forest-dwelling communities. Will DFOs, range officers, foresters or even forest guards in Anantnag dare tell forest-dwellers living in remote Kokernag, Pahalgam, Breng, Shangus, Gadole or other forest areas that the tribal communities would have to surrender their rights and titles to land which is under their possession as tribals?

Instead, the Deputy Commissioner could have directed sub-divisional magistrates, district panchayat officers (DPOs), tehsildars or block development officers (BDOs) to do the work of spreading information, or it could have involved reputed NGOs.

Even at the top levels of government, the responsibility of implementing the FRA is being given to the forest department, while the tribal affairs department or even the panchayati raj department have been sidelined.

FRA in India?

The preamble of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) recognizes the rights of tribals and traditional forest dwellers and vests those rights in them. It reads:

"[This is] An Act to recognise and vest the forest rights and occupation in forest land in forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest-dwellers who have been residing in such forests for generations but whose rights could not be recorded; to provide for a framework for recording the forest rights so vested and the nature of evidence required for such recognition and vesting in respect of forest land."

The preamble explains the background of this law and its aims and objectives as follows:

"Whereas the forest rights on ancestral lands and their habitat were not adequately recognised in the consolidation of State forests during the colonial period as well as in independent India resulting in historical injustice to the forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest-dwellers who are integral to the very survival and sustainability of the forest ecosystem and whereas it has become necessary to address the long-standing insecurity of tenurial and access rights of forest-dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest-dwellers including those who were forced to relocate their dwelling due to State development interventions...."

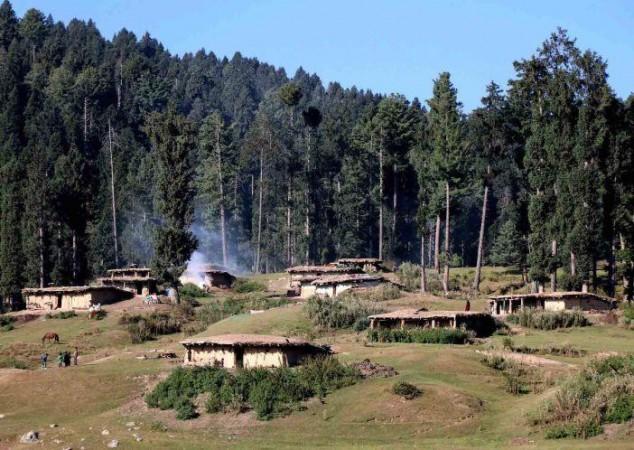

A large population lives in and around forests in Jammu and Kashmir, especially the Scheduled Tribes such as Gujjars, Bakerwals. There are also other traditional forest dwellers such as Kashmiris, Pahadis or even Dogri-speaking people of Jammu and Kashmir, who have lived in and around forest areas for very long and in a symbiotic relationship with each other and the forests.

This symbiosis has fostered formal and informal customary rules of use and extraction from forests, which are often governed by ethical beliefs and practices that ensure forests are not denuded.

During colonial rule, the British shifted the focus away from forests as a resource that sustains local communities to one that is owned by the State and exploited for commercial interests such as in dams, railways, mining, and to clear land for agriculture.

Several legislations and policies, such as the Indian Forest Acts of 1865, 1894 and 1927, were introduced by [central] governments. Some state forest acts also curtailed centuries‐old customary rights of local communities.

This continued even after Independence until the FRA was enacted in 2006 and rolled out across India in 2008 (except Jammu and Kashmir). Still, it took another 14 years to extend this law to Jammu-Kashmir.

Gram Sabha or closed-door meetings

Now the government is taking hasty decisions to enforce the FRA. The gram sabhas, which have been empowered to implement this law, have hardly assembled in the tribal belt due to the harsh cold weather. Villages near forests are covered in four or five feet of snow. It is therefore impossible to make people assemble to discuss their forest rights.

Taking advantage of the weather, fake gram sabhas have been held behind closed doors in Jammu and Kashmir. Before holding gram sabha meetings, the government is supposed to issue a gazette notification through the Jammu and Kashmir tribal affairs department. The government is supposed to provide details of the villages where people can claim their rights under the FRA and so on. Yet in Jammu and Kashmir, everybody is still unaware of whether the tribal affairs department has been made the nodal body to implement this law, or not.

Most FRA meetings have been organised by the forest department, and this also goes against the principles of this legislation. Is it that the government first patronised meetings behind closed doors, then labelled them as meetings of "gram sabhas"?

There is resistance from people as well: ten or 15-member Forest Rights Committee (FRC) members have been elected in these meetings, but people, including government officials, are confused about whether the FRA has to be implemented by 31 March. This is not at all true: the FRA is a continuous process with no time period for its implementation.

There are more than 5,000 village panchayats in Jammu and Kashmir. The average population of villages is more than 2,500, and not even one percent of them have participated in the FRA gram sabha meetings. This is killing the spirit of the law.

Reality on ground

When not even 14% tribal and other traditional forest-dwellers have benefited from the FRA nationally, how can the government of Jammu and Kashmir hastily decide to implement it in just a few months? Prime Minister Narendra Modi talks about giving more powers to panchayats in the state—then why is this not actually happening on the ground?

The gram sabhas were not even held in a majority of the villages where the 15-member village FRCs have been constituted. Sarpanches and panches and other influential persons have been made members of FRCs.

Can the government produce even a single video clip wherein one dozen women can be seen participating in these gram sabhas? In fact, there is chaos in each forest village. Further, there was negligible participation of women, in just a handful of gram sabhas where actual [valid] meetings were held.

Let the people and officials of the forest, rural development, panchayati raj, land revenue and tribal affairs departments be trained and sensitised on the FRA. If the tribal affairs department does not have enough manpower for this at the district or block levels, then government teachers, ICDS employees, and other officials can be asked to join this department on deputation (for two years or longer), so that the FRA can be properly rolled out.

The gram sabhas must elect FRCs again once the weather improves. Until then, the focus should be only on building awareness and educating people on their rights under this act. The closed-door gram sabhas should be declared null and void.

[Dr Raja Muzaffar Bhat is Chairman of Jammu & Kashmir RTI Movement. He is also an Acumen India fellow from 2017 cohort. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect those of International Business Times, India]

!['Had denied Housefull franchise as they wanted me to wear a bikini': Tia Bajpai on turning down bold scripts [Exclusive]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806605/had-denied-housefull-franchise-they-wanted-me-wear-bikini-tia-bajpai-turning-down-bold.png?w=220&h=138)