Politicians, policy apparatchiks and technocrats who went red in the face cheering the benefits of demonetisation could take a lesson from the ongoing competition between the states to announce loan waivers for farmers who have piled on crop loan burdens. The lesson is one of differentiating between politics and fact – the latter, a department where government flops repeatedly, cheered along by the bureaucracy and party rank and file.

Farm loan waivers, starting from the first one announced by the Janata Dal government of VP Singh in 1990 to the one stewarded by the UPA government in 2008, have been exercises in futility. In southern and central India, farmer stress has been guided by failing monsoons when it comes to the rabi and kharif crops; unseasonal rains, diseases and storms play their part in destroying contentious crops like cotton, which in recent years, has led to largescale farmer suicides.

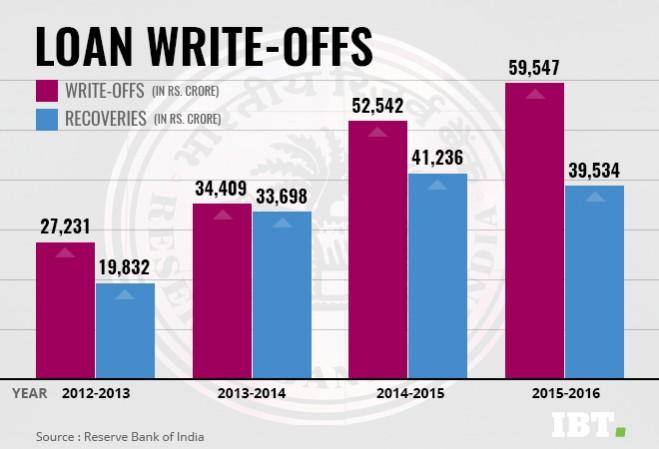

Loan waivers always play out their counter-productive effects on the economy, inflating non-performing assets (NPAs) and battering the bottomlines of India's public sector banks, which held Rs 6.4 lakh crore in bad assets as of March 2017. Besides adding to taxpayer outgo and widening the fiscal deficit, out-of-turn loan waivers have another set of outcomes – fresh rounds of farm stress, and the inevitable cycles of agitation and violence, appeased through future loan waivers.

Different parties, same tub

The political class may have realised that good politics is a house built on the foundation of bad fact and bad logic perpetrated with an eye on the rural votebanks. But the loan waivers will be far from ideal placebos for the folks at the farm. A substantial part of farm loans comprise non-crop loans like tractors, ploughing machines, and input costs largely untouched by the proposed waivers.

Top guns of the ruling BJP dispensation who had wasted no time in criticising the evils of a humongous loan waiver announced by then Congress Finance Minister P Chidambaram nine summers ago, -- saying that distressed banks would be weighed down by further pressures on their NPA positions, and that zero interest farmer loans were simply not the way ahead – have always thrown their weight behind incentivising farmer loan defaults. BJP leaders have been grandstanding on the benefits of loan waivers to farmers in a sector where genuine farmers are often not identified with a fair degree of accuracy or where temporary farm hands masquerade as farmers to avail of loans.

Without forgetting the huge potential for impersonation thrown up by a corrupt rural banking system, it is well known that high amounts of loan pilferage have been frequently reported in the farm sector. A Parliamentary Public Accounts Committee has noted serious implementation glitches in the Rs 52,000-crore debt waiver scheme announced by P Chidambaram in 2008. The Committee conducted a sample of 90,576 beneficiaries/farmers spread across 25 states out of the intended 3.69 crore base. Discrepancies were found in 22 percent of the cases.

Defaults vs low lending

An inverse parallel that can be drawn to irrecoverable loans is that India's farm policy often does not support on-ground sales requirements of its farmers. Rural lending growth collapsed to 2.5 percent in the second half of 2016-17 and even shrank in several states, including Punjab and Maharashtra, even though banks are flush with funds ferried in through demonetisation. This also explains the higher provisioning by banks in the second half of the year, after banks realised their inability to efficiently close their NPA books in the face of growing defaults by the farm sector.

Many a gaping hole in the loan recovery process are persistent painpoints. Take the case of public sector lender State Bank of India. As of April 1, 2015, the bank had Rs 56,725 crore of bad loans, or gross NPAs. During the course of the year, Rs 4,389 crore of bad loans was recovered. At the same time, the bank wrote off Rs 15,763 crore of bad loans, more than three times the loans it had recovered. By March 31, 2016, the total bad loans of the bank had segued to Rs 98,173 crore thanks to fresh bad loans tagged onto its rural portfolio.

During every period of farming sector stress the cycle of agitation and loan waivers could be repeated. The root causes of agrarian distress have not been addressed by repeated refinancing of farmers whose ability to repay is always in doubt, leading to distorted credit histories and banks refusing to lend them loans in future. The money goes on the government's books and would be recovered through the two most popular routes – higher indirect taxes through innovations like GST or add-on cesses in the Union Budgets or via higher public and overseas borrowing.

Official policy and the machinery implementing it are now on the same page, where the symptoms are treated, but not the malaise. Farm loan waivers present a glaring example where the malaise is being glossed over at the expense of larger economic and social goals. Such a non-strategy would not really add positive chapters into India's larger growth story. Rather, it would be an open invitation to disaster.

!['Had denied Housefull franchise as they wanted me to wear a bikini': Tia Bajpai on turning down bold scripts [Exclusive]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806605/had-denied-housefull-franchise-they-wanted-me-wear-bikini-tia-bajpai-turning-down-bold.png?w=220&h=138)