It ultimately comes down to ideology versus votes -- there are parties that aim for the transformation of the country and there are parties that are simply concerned with winning elections.

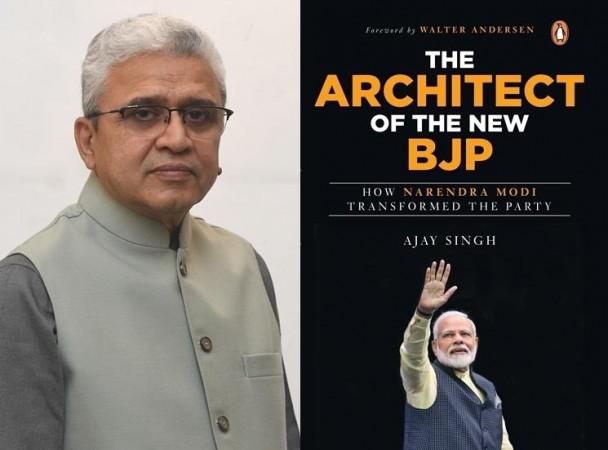

"A party with a strong ideological foundation is likely to depend more on cadres, for the sake of ideological purity. A party with only vaguely defined ideologies, if at all, and more attuned to a set of broad-based values would prefer to interact with the masses keeping only a relatively small bunch of core workers. Another way of putting it is that there are parties that aim for the transformation of the country, and there are parties that are concerned simply with winning elections," veteran journalist Ajay Singh, currently the Press Secretary to the President of India, writes in 'The Architect Of The New BJP -- How Narendra Modi Transformed The Party' (Penguin).

"When the Bharatiya Jan Sangh (BJS), the BJP's forerunner, was founded in 1951, with the help and support from the RSS, right from the outset it adopted a sharply different party-building strategy, one that fore-grounded the ideology and the indoctrinated cadre, and hence an organisation," Singh adds as he traces the rise of Modi from the time the BJP came into existence in April 1980, when it came out "intact without much attrition in its organisational network and membership" from the Janata Party that had been formed ahead of the 1977 General Elections that dumped Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in its anger against the Emergency that she had imposed from 1975 to 1977.

A decade earlier, the BJS had gained substantially in the 1967 Assembly election in terms of political experience by participating in the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal (SVD) coalition governments in several states but had still not acquired a significant footprint across the country, Singh writes.

"Its area of influence was largely confined to the Hindi heartland, and the eastern and southern parts of the country remained beyond its reach. The party's social outreach was also limited to urban sections and upper castes, though it drew large sections of cadres from rural areas and OBCs."

Apart from the singular focus on "idealistic" popular support, there was also the popularity of the Congress under Jawaharlal Nehru to contend with. The masses continued to support the party that was at the vanguard of the freedom movement. With the advent of Indira Gandhi, there was a massive overhaul of the Congress in terms of its vision and leadership as well as in its ways of winning power, the author states.

"In the early 1970s, however, her mis-governance and rising inflation were making her unpopular. A students' revolt in Gujarat in 1974 against Indira Gandhi spread across India and metamorphosed into a widespread agitation. Veteran socialist-Gandhian Jayaprakash Narayan assumed the leadership of this movement. The BJS then found a unique opportunity to expand its influence by aligning itself with this campaign. Indira Gandhi, in reaction, overplayed her hand and imposed the Emergency, giving the opposition parties the first chance to gain popular support," Singh writes.

The resultant political scenario brought anti-Congress forces together under the banner of the Janata Party, into which the BJS merged itself. For the first time, the BJS gained experience in leading a mass movement across the country by aligning with ideologically disparate political forces, he adds.

The Janata Party experiment was short-lived and in its disintegration, the BJP began its political journey on quite a moderate note, under the leadership of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, with 'Gandhian socialism' as its guiding philosophy. However, the party was jolted on its electoral debut in 1984 with its worst performance in the Lok Sabha polls held in the wake of Indira Gandhi's assassination. The BJP won only two seats as all its leading lights, including Vajpayee, were defeated.

"That was the worst phase for the party and the cadres that formed the backbone of its organisational structure. Since 1984, however, the country has witnessed only the rise and rise of the BJP, and this trend rarely faltered. Though the Hindu nationalist ideology remained its unique identity, the party sought to connect with the masses on a host of other issues too," Singh writes.

The Hindutva view also started gaining traction among the masses, thanks to myopic and power-centric policies of the Rajiv Gandhi government, as exemplified by its 1986 reversal of the Supreme Court judgment in the Shah Bano case on the one hand, and the opening of the locks of the Babri Masjid in the same year on the other.

Rajiv Gandhi's successor, V.P. Singh, also inadvertently helped the BJP's cause by implementing the Mandal Commission recommendations for reservations for OBCs in education and government jobs in 1990.

Also, the two party presidents after Vajpayee (1980-86) -- L.K. Advani (1986-91, 1993-98) and Murli Manohar Joshi (1991-93) -- campaigned aggressively on Hindutva, conducting a series of agitations and yatras, the chief among them being the Ram Janmabhoomi movement for building a Ram temple at the site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, Singh writes.

Modi was not only a keen observer of these developments but also a key organizer of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, he adds.

"He was an active RSS worker during the Emergency, when Indira Gandhi banned the organisation. (He was active in the underground and overground campaigns against the undemocratic and authoritarian moves of the government.) He assessed at close quarters the ups and downs of politics, which were often driven by personal ambitions rather than national and social interests.

"In understanding the course of politics, he acutely sharpened his social understanding and significance of the organisation in sustaining a political movement. He was aware of the fact that the dissonance and discord between the organisation and the government had been taking its toll on the Congress, which was gradually reduced into a motley group of family retainers and rent-seekers led by the Nehru-Gandhi family scions," Singh maintains.

Post the "phenomenal success" of the BJP in the 1989 and 1991 elections, Modi shifted from the RSS to the BJP "and, in close coordination with the top party leadership, he began shaping the organization in Gujarat through his innovative methods of expansion... If he was innovating techniques, he also remained committed to the core values as a long-time RSS pracharak," Singh writes.

"Unlike traditionalists within the BJP, Modi has always been acutely conscious of the reasons that prove to be the undoing of political parties that fail to adapt to the changing times. Till the '90s, the BJP's organisational expansion was seen as the party's outreach among people through its trained cadres. Modi singularly changed the definition of expansion by including infrastructure as a basic necessity for the growth of the party," the author adds.

Modi's innovations in the states where he held the charge "laid a solid foundation for the future growth of the party and attracted attention. In his role as party builder, he did not remain ideologically rigid and was seldom guided by prejudices or political dogmas...Though he faced criticism, he stayed the course against all odds and won the day eventually," Singh maintains.

As the Gujarat Chief Minister, "he honed the skill of seamlessly aligning the organization with the government's social programmes. He remains consistent even as prime minister to focus on the growth of the BJP, which has become the world's biggest political party".

Unlike Vajpayee's National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government that faced dissonance from the Sangh Parivar's constituents, Modi's NDA government "remains in perfect alignment with the Sangh Parivar. He fits into the role of a 'classical sangthanist' (organising secretary) whose tactical moves would eventually benefit the ideology in the long run".

"At this stage, Indian politics has almost returned to single party dominance, with the BJP looming large like a colossus and Modi as an indomitable giant among today's leaders from all parties. This scenario was inconceivable to even the most perceptive political observers barely a decade ago," Singh points out.

As Modi's stature grew and he achieved exceptional popularity, he went beyond the prevailing political idioms and lexicons in his dialogue with the masses. "Modi's eloquence, though much praised and a key aspect of his image, was no match to Vajpayee's oratorical prowess. But for an impatient young India tired of old political platitudes, Modi's style, dramatic touches, punch lines and engaging tone found instant traction in the post-Vajpayee era."

"His attraction was as much visible in the south as in the Hindi heartland. Across the country, he managed to evoke hope among people who were looking for a political alternative. (He insists) that he does not believe charisma alone can sustain people's trust for long. There are a number of political personalities endowed with exceptional charm, yet it can do little for them," the author writes.

That is why Modi consistently refers to Mahatma Gandhi to contextualize his politics.

"He believes in taking his ideas to the masses and getting their acceptance as an index of approval. Arguably, the secret of Modi's success in groundbreaking methodological innovations is remarkable flexibility. The underlying pragmatism of the RSS encourages and welcomes creative and radical departures from the playbook.

"Ever since his induction in the party, Modi has deployed unorthodox techniques, caring little for the old-fashioned dogmatic ways of expanding the organization. Yet, he met with no censure. Indeed, his ways were accommodated within the Sangh's scheme of things" as it "readily embraces the ideas that may not be ideologically compatible but get social traction," Singh points out.

The Congress dominance, with the Nehru-Gandhi family at the top, is understood by Modi as a "civilizational disruption" in the absence of personalities like Mahatma Gandhi. "Modi seems to be making no such mistakes. That he would not stand on prestige despite his image of a strong leader was evident when he withdrew the three bills on agriculture reforms in late 2021," realising that they were being taken as a pretext to foment a subversive movement not only within India but also by external forces, Singh writes.

He also apologised, underlining that his intent was benevolent but he might have erred in judgement, the author adds.

"Modi perhaps stands alone in contemporary politics for having taken decisions that entailed hardships for people. Demonetization and the lockdown amid the pandemic are good examples. But he always owns up his responsibility for each of them and never indulges in passing the buck. None of those difficult decisions have caused any erosion in people's trust in Modi or in the credibility of his government, because people do not find any fault with his intentions," Singh maintains.

"As a result, the BJP has achieved a scale of dominance attained by the Congress immediately after Independence that continued for decades," he adds.

Looking ahead, Singh poses a pertinent question and provides the answer: What will the BJP's future be under Modi and beyond him; will the dominance achieved by the BJP be transient or will it last long?

"In the course of its political journey, the BJS/BJP not only gained experience in mass movements but also expanded its organisational network to get real feedback from the ground. This helped the party leadership in getting a feel of the pulse of the people...When Modi started campaigning for the 2014 Lok Sabha election, cadres galvanized into action as they could see that he was gaining exceptional popularity," Singh maintains, and points to the grooming of a large number of next-gen leaders, at both national and regional levels, who have also been learning expansion methods from the top leadership.

"As of now, the BJP has successfully filled the vacuum caused by the exit of the Congress as a national party. Unlike the Congress, which degraded its vast organizational network and rendered it effete, Modi ensures that the organization is not a political expedient for the government. He has created a unique harmony between the government and the organisation, which never existed before.

"This predominant political position is unlikely to be unsettled in a post-Modi phase, as he will be leaving behind a robust political structure that will keep on creating its own icons of the time," Singh concludes.