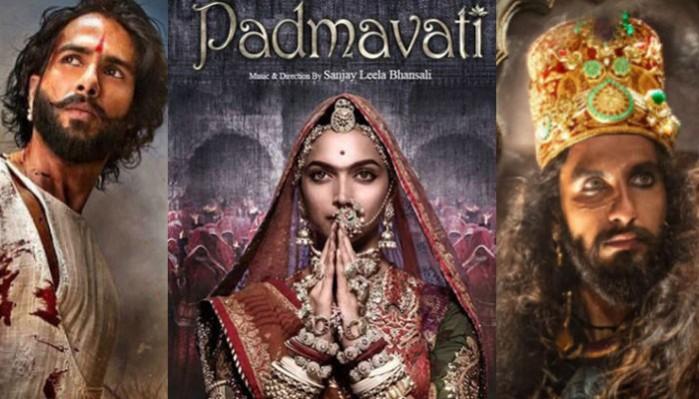

As state after state bans Sanjay Leela Bhansali-directed Padmavati in protest against the movie's contents purportedly hurting sentiments of its people, the film still awaits clearance from the Central Board of Film Certification.

In what is being called an intentional delay in sending the film to the board prior to the release of the film — scheduled for December 1 — board head Prasoon Joshi has minced no words. The paperwork is incomplete and the disclaimer stating whether the film is work of fiction or historical has not been stated, he has noted.

Meanwhile, the price on director Sanjay Leela Bhansali and actor Deepika Padukone's heads have gone up from the Rs 10 crore offered by a senior Haryana BJP leader.

Surprisingly, the clean chit for the movie has come from none but the liberals' much-disliked news anchor-turned-head of channel Republic. Arnab emphasises that the movie is nothing but an ode to Rajput valour with nary a derogatory scene.

So why did Bhansali allow the ruckus to snowball into a country-wide controversy? Why has he maintained silence all along? Surely he could have screened the film to the Karni Sena, which has been at it since the shooting of the film began.

All it required was for the director to call all the protesting parties and screen the movie. Why did he choose instead to pick a few journalists alone?

It makes one suspect that either Bhansali was counting on the controversy to raise public curiosity and viewership, or he has, since winding up shooting, done some quick and smart editing.

Knowing the famed chemistry between Deepika Padukone and Ranveer Singh, it is a little difficult to believe that the duo does not share screen space even in a single shot.

To begin with, those in support of Bhansali said the film was fictional and was based on a poem by 16th century Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi. But Khilji is no fictional guy, nor is Padmini.

As parallels were drawn showing evidence of the story being borrowed from history, the tone changed and started to say that history is not rigid and that multiple versions should be accepted.

Multiple versions suit the polarised society of today, where according to one's political alignment, one not only interprets history but emphasises that version as THE truth. For instance, one writer in Firstpost sees the present "hungama" as further proof of the Rajput complex from failing to protect its subjects in the past! And hence a need to fall back on practices like Sati and "the legend of Padmini" to retain a sense of glory!

Another writing in Daily Pioneer traces it to the deep distrust among the Hindu majority about the history of India written by "pseudo-secular, Nehruvian and Marxist historians".

To the claim that nowhere in history is the story of Padmini written, Rama Lakshmi counters in her article in The Print that a lot of Rajput history was preserved through oral retellings, as in ballads. "Not all of them had the luxury of Darbari chroniclers like the ruling Mughals did," she says.

Different viewpoints are fine but why is only a certain community expected to take it all lying down, ask the opponents. There is a point there. Take for instance the still-banned movie "Mohalla Assi" and its crude depiction of Lord Shiva mouthing inanities.

Showing the madness and badness behind present-day Varanasi is one thing, but packing a film with irreverent language guaranteed to hurt public sentiments is another. The CBFC cannot be blamed for banning that film.

In the case of Aligarh, depicting homosexuality, again the certification caused a problem as the board denied a UA rating saying it was not suitable for children. That too made sense. In the name of freedom, do we want to thrust confusing images and ideas into the minds of the young, however ubiquitous such information is today?

Padmavati brings to the centre stage the question: How much licence can one take with history? And what role does cinema play in using or abusing history? Is it meant to inspire, reflect, entertain or act as an agent provocateur?

We have many filmmakers who thrive on taking a story from history or mythology and turning it upside down. When drawing mileage from the script by claiming it to be based on real-life events, is it ethical to distort facts?

How far can one take freedom of expression? Can one be excused for playing with the sentiments of the masses, however narrow-minded or regressive one sees them as?

This freedom, while conferred on every Indian in the Constitution, is not an absolute right. Article 19 of the Indian Constitution says: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression, this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers."

Clause (2) of Article 19 imposes restrictions on the right by cautioning on public order and defamation (injuring reputation). In this case it is seen as defaming a lineage of Rajputs and queens.

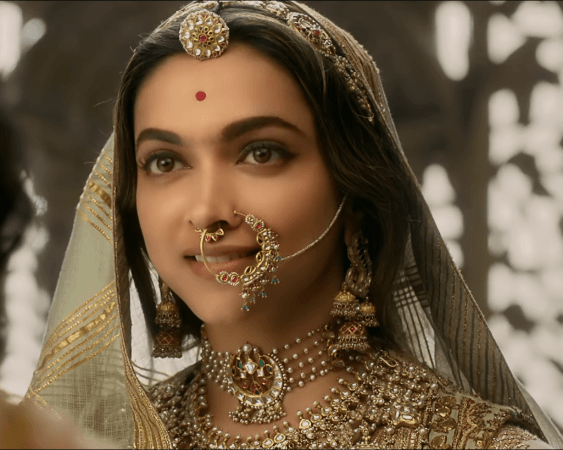

Rajput queens were revered for their fidelity and in the imminence of capture by the enemy would throw themselves into a fire. Given such a legend, it would seem a sacrilege to even suggest that one queen agreed to meet the invader, let alone dance with him!

Of course, the latest versions deny any such attempt. And yet, the critics were not invited for a screening...

It is true that history is more than a set of facts, and renders itself for many versions based on many interpretations. But, while claiming a story to be historical in origin, should not the artiste retain the main premise or the larger accepted version?

Above all, to put it in the words of Bollywood superstar Aamir Khan, shouldn't one exercise social responsibility in the use of the freedom of expression?