Roy Grissom was lying in bed one morning in 2011 when his house in Oklahoma suddenly shook. Heavy concrete window sills ripped from the walls, pulling out chunks of brick as they fell. The older home's foundation split and the plaster ceiling began to crack. The house shuddered again, and then again.

Grissom never expected to feel an earthquake in Prague (pronounced "PRAY-geh"), a town of 2,500 people settled by Czech immigrants. "Fires or tornadoes, sure, but not an earthquake. Not in Oklahoma," the former school superintendent told International Business Times.

The 5.7-magnitude earthquake – the strongest in the state's history – and a series of related shocks destroyed 13 other homes and injured two people that November, racking up nearly $1 million in damage across the small town.

This spring, federal scientists confirmed the quake's likely cause: Wastewater from oil and gas operations -- created by both conventional oil drilling and modern techniques like fracking -- had been injected in the ground near a fault zone, triggering the seismic reaction. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) dubbed the eventthe "largest human-caused earthquake associated with wastewater injection."

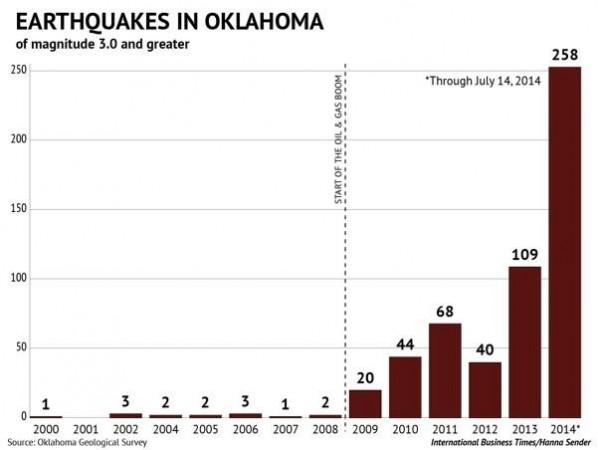

The Prague quake is only the most powerful of the hundreds of temblors that have rippled across Oklahoma since the boom in oil and gas production got underway in 2008. So far this year, Oklahoma has experienced about 260 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater, more than in California and up from an earlier state average of just two a year. (At magnitude 3.0, quakes are strong enough for people to feel but usually weak enough to cause only minor, if any, damage to homes and buildings. Hundreds of magnitude-2.0 tremors are also hitting Oklhoma but are often undetectable above ground.)

Other fossil fuel-rich states have also experienced more quakes than usual in recent years, including Arkansas, Colorado, Ohio and Texas. Not every state may be as vulnerable to seismic shifting as Oklahoma is, a state criss-crossed by major fault lines, particularly in its central region. But the Oklahoma earthquake swarm may still be a warning for states where fracking operations are on the rise, said Robert Williams, a geophysicist with the USGS Earthquake Hazards Program in Golden, Colo. "Regulatory agencies are looking at the results coming from Oklahoma ... and can take away some lessons."

He said that scientists are "not worried that we're going to replicate Oklahoma in every location, and we don't expect that to happen. The geology changes across the country, and so you have to be careful about extrapolating forecasts into other geologic settings." Even so, he said, "We're still fundamentally concerned about earthquake triggering in general" across the country.

Scientists are increasingly convinced that the spike in earthquakes in oil- and gas-producing states can be tied to wastewater injection wells, although some energy firms and industry officials dispute the link.

Oklahoma residents say they want answers. "It's very stressful," Nancy VanDeVeire, a retired schoolteacher in northern Oklahoma County, just west of Prague's Lincoln County, said about the frequent shaking and thunder-like roar of the earthquakes. "You walk around your property and think, 'I'm glad it's still here today, that it hasn't fallen into a hole.'"

VanDeVeire said the quakes regularly wake her and her husband in the middle of the night. Sometimes the rumbling lasts for hours; it can be hard to fall back asleep. Increasingly worried, she attended a town hall-style meeting hosted by state representatives in the nearby city of Edmond. The June 26 event, initially expected to draw 150 people, saw more than 700 Oklahomans cram into the pews of the Waterloo Baptist Church. "There are a lot of people that have been quite upset," VanDeVeire said.

At the town hall meeting, the first question posed to state regulators and geologists was why injection wells are still being used despite the swarm of earthquakes. When scientists explained that they need to keep the wells open to collect additional data, some of the crowd responded with boos and screams, KOKH-TV reported.

Dozens more residents lined up to ask questions -- a surprising number of themhostile toward the oil and gas industry, given that the sector directly or indirectly supports one in six jobs in the state, according to industry figures. Oklahoma is the fifth-largest oil producer and the fourth-largest gas producer in the United States.

Energy companies say that disposing of wastewater is central to their operations, and that a temporary ban on injection wells would bring their oil drilling and fracking -- formally called hydraulic fracturing -- to a halt. Both processes produce copious amounts of chemical-laden wastewater, and the cheapest and easiest way to get rid of it is by injecting it deep underground, energy firms say.

A spokesman for the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, the state's public utility regulator, explained at the town hall that it doesn't have the authority to issue a moratorium on injection wells, though it is taking steps to reduce the risk of seismic activity. For example, earlier this year regulators said they would no longer approve permits for disposal wells in earthquake-prone areas without additional information from applicants. And the commission will soon require operators to supply real-time data related to well pressure and volumes so that scientists can better study the link between seismic activity and wastewater injections.

In Prague, dealing with earthquakes has become a part of daily life. Andy Evans, the superintendent at Prague Public Schools, said he constantly searches for cracks and damage in the district's four school buildings. Many doors are out of plumb. A recent project to install doors connected to a security system ran $15,000 over budget because eight doors had to be reset in their frames, he said.

The school district has adopted a "duck and cover" earthquake safety drill for students, during which children must hide under their desks. The school's insurer, Oklahoma Schools Insurance Group, also requires that bookcases be attached to the walls to keep them from toppling over on students and teachers.

"It's really freaky around here, because you hear the earthquakes," Evans said, describing the quakes' sound like a "jet engine roar," though he said the tremors have quieted down in recent months.

According to the USGS, wastewater injection wells can cause earthquakes by prying fault lines apart. Normally, faults are pushed together by overlying rocks; the weight and stress applied by these rocks increases fault's frictional resistance. But injected wastewater, depending on its volume and location, can counteract these forces and cause the faults to "slip," which triggers earthquakes, the agency explained on its website.

About one-fifth of the earthquakes felt in Oklahoma in recent years can be tied to just four injection wells, scientists at Cornell University found in a July 3 study. The state has more than 4,000 active disposal wells overall.

The Oklahoma Independent Petroleum Association, however, argues that more research is needed to prove a correlation between wastewater injections and the Oklahoma earthquake swarm. Lewis Moore, a Republican state representative, disputed that the earthquakes could be man-made."It's just science. There are some things that human beings cannot stop," Moore said. "Just like if the Earth is going to warm, there's nothing we can do to stop it."

Glen Brown, vice president of geology at Continental Resources Inc. (NYSE:CLR), a major petroleum liquids producer, said his own research shows that the current Oklahoma phenomenon is likely related to the uptick in seismic activity worldwide. It also mirrors an earthquake swarm that shook Oklahoma some 60 years ago, he said. Brown is slated to present his findings to the Oklahoma Geological Survey (OGS) next week.

"I believe that what's going on in Oklahoma today is natural swarm of very small magnitude and very small impact," Brown said. "Quite frankly, the way that people are talking about it is overexaggerating what's going on."

The USGS and OGS are saying otherwise. In May, the agencies issued a joint statement alerting Oklahoma regulators, state government officials and building owners to the growing possibility of more-damaging earthquakes. Based on historic seismic data, a higher frequency of smaller earthquakes, ranging from magnitudes of 2.0 to 4.0, tends to raise the likelihood of more-powerful events in the future.

The damage could be especially high in historic town centers with brick buildings and in older homes with brick chimneys, which are already toppling from the seismic shaking, Austin Holland, a seismologist at OGS, said. This spring the state-run OGS brought on another analyst to evaluate earthquake locations and magnitudes and hired another seismologist to study the quakes' depths, orientations and potential links to oil and gas activities. "It's a real challenge for us as a state agency to keep up with the workload," he said.

Despite unease about the earthquakes, many Oklahomans are hesitant to cast off oil and gas companies, which provided the state nearly $2 billion in total direct tax payments in fiscal year 2012, according to an Oklahoma State Chamber report.

"We are all concerned about the potential effects that [wastewater] injection can have, but the oil companies have been extremely responsible when there has been an issue," said Evans, the Prague school superintendent. "Please remember that most of these people live here. It doesn't benefit them very much to have their wells shaken apart."

VanDeVeire, the retired schoolteacher, called the earthquake situation "a quandary."

"I truly believe that we need to be more energy independent, and it's hard to do that if you limit the companies that are addressing that issue for us," she said. "So how can you do this without putting everyone at risk? I just hope they figure out a way to deal with it that's less disturbing."