Most people would go cold with fright at the sight of a snake. Armed with venom or bone-crushing strength, and being at the center of scores of myths, these slithering reptiles have a separate phobia associated with them— ophidiophobia. However, snake venom, which can often stop hearts or eat into flesh, may actually save lives. Scientists have reported that a 'super glue' derived from the venom of an extremely poisonous snake can be used to stop bleeding.

According to an international study, a bioadhesive gel or tissue sealant synthesized from the venom of lancehead snakes (Bothrops atrox)—one of the most poisonous snakes found in South America—can instantly stop severe bleeding. All that has to be done is apply the glue to the wound and shine a light on it to seal the area. The findings were published in the journal Science Advances.

"During trauma, injury and emergency bleeding, this 'super glue' can be applied by simply squeezing the tube and shining a visible light, such as a laser pointer, over it for few seconds. Even a smartphone flashlight will do the job," said Dr. Kibret Mequanint, co-author of the study, in a statement.

Limitations of Existing Bioadhesives

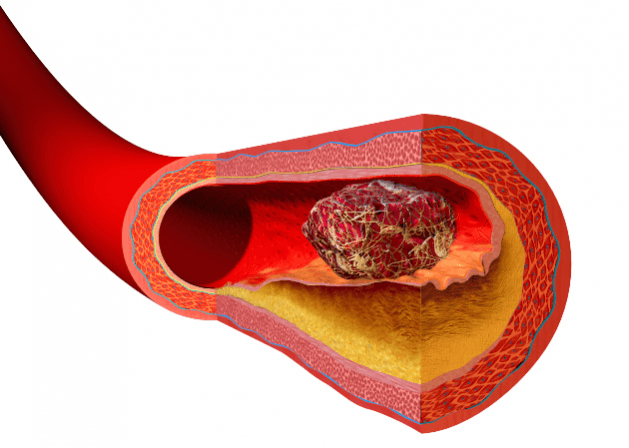

During the natural process of bleeding or hemostasis, platelets aggregate at the site of blood loss. Fibrin, a protein, forms as mesh over the accumulated platelets and results in the formation of a hemostatic plug or clot over at the site of the wound. This creates a temporary sealant aimed at controlling the bleeding. While existing bioadhesives—synthetic and naturally derived adhesives—aid in sealing wounds such as during surgery, they are bound by limitations.

Synthetic adhesives are derived from substances such as polyethylene glycol and cyanoacrylates. Their use is limited by their toxicity as their degradation can often result in inflammatory responses. Natural adhesives are obtained from albumin, fibrin, gelatin, and polysaccharides. However, their adhesive ability and mechanical integrity can often be low. In presence of large amounts of blood, the binding ability of both classes of bioadhesives can be impaired.

Creating A Snake Venom 'Super Glue'

Through their collaboration, the team looked into a blood-clotting enzyme called batroxobin, which is also known as reptilase, that is present in the venom of lancehead snakes. The venom is said to possess procoagulant (promotion of clotting) activity where fibrinogen, liver-produced protein, is rapidly converted to fibrin.

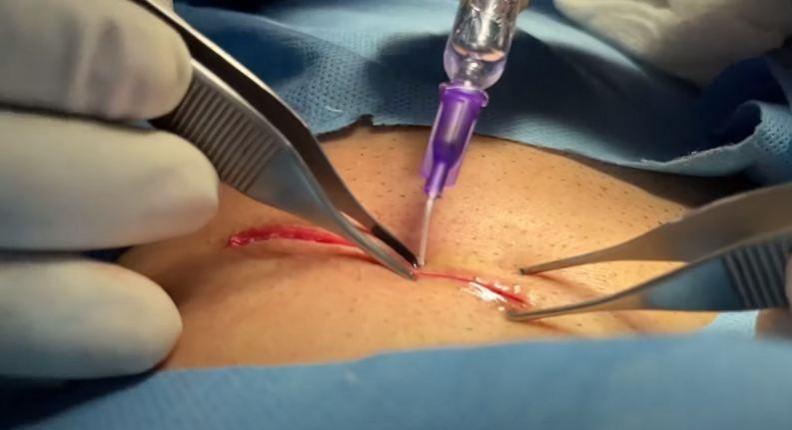

Therefore, the authors developed a new hemostatic bioadhesive (HAD) by integrating the enzyme from the venom with a modified form of gelatin (methacrylated gelatin). Visible light was used to promote the quick polymerization of the gel, which resulted in the cross-linking of the HAD.

Exceptional Binding Strength

It was found that in comparison to clinical fibrin glue—which is accepted as the gold standard for field and clinical surgeons—the new bioadhesive had 10 times the binding strength to withstand loosening or being washed away by bleeding. In addition to stronger adhesiveness, the clotting time was significantly shorter. While fibrin glue requires 90 seconds, the new tissue required only 45 seconds.

The snake venom 'super glue' was tested in models for ruptured aortae, deep skin cuts, and acutely injured lives, all of which are regarded as critical bleeding scenarios. "We envision that this tissue 'super glue' will be used in saving lives on the battlefield, or other accidental traumas like car crashes. The applicator easily fits in first aid kits too," expressed Dr. Mequanint.

Along with practical on-field applications, the 'super glue' can be utilized for the closure of surgical wounds, potentially eliminating the need for sutures. "The next phase of study which is underway is to translate the tissue 'super glue' discovery to the clinic," concluded Dr. Mequanint.

!['Had denied Housefull franchise as they wanted me to wear a bikini': Tia Bajpai on turning down bold scripts [Exclusive]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806605/had-denied-housefull-franchise-they-wanted-me-wear-bikini-tia-bajpai-turning-down-bold.png?w=220&h=138)

![Nayanthara and Dhanush ignore each other as they attend wedding amid feud over Nayanthara's Netflix documentary row [Watch]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806599/nayanthara-dhanush-ignore-each-other-they-attend-wedding-amid-feud-over-nayantharas-netflix.jpg?w=220&h=138)