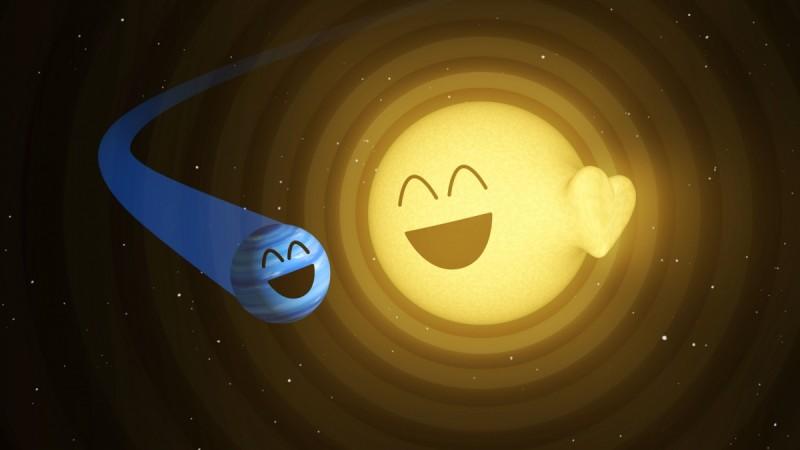

NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope caught a glimpse of an intergalactic romance 370 light years away.

Also Read: Violent beginnings of a supernova spotted by researchers for the first time!

Vibrations were detected from the outer shell of a star, dubbed HAT-P-2, by the Spitzer Space Telescope. Scientists think the pulsations are caused by a closely orbiting planet called HAT-P-2b.

"Just in time for Valentine's Day, we have discovered the first example of a planet that seems to be causing a heartbeat-like behaviour in its host star," said Julien de Wit, postdoctoral associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge. A study describing the findings was published today in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

NASA's Kepler space telescope had discovered a similar phenomenon between numerous binary star systems that orbited each other, termed "heartbeat stars".

Exoplanet, HAT-P-2b, is a hotter version of Jupiter, weighing around eight times the gas-giant and its star is comparatively 100 times more massive.

The pulsation effect is an outcome of the size difference between the star and the exoplanet.

"It's remarkable that this relatively small planet seems to affect the whole star in a way that we can see from far away," said Heather Knutson, assistant professor of geological and planetary sciences at Caltech in Pasadena, California, as per a NASA statement.

The exoplanet, HAT-P-2b, was fascinating for the astronomers because of its elliptical orbit. The planet close in on the star every 5.6 days and receives 10 times more luminosity when it's at the closest point compared to the farthest.

Gravitational energies of both the celestial bodies interact with each-other which results in making the star emit heartbeat-like pulsations.

"We had intended the observations to provide a detailed look at HAT-P-2b's atmospheric circulation," said Nikole Lewis, co-author and astronomer at Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, as per a NASA statement.

"The discovery of the oscillations was unexpected but adds another piece to the puzzle of how this system evolved," Lewis added.

This interaction between the planet and the star was captured by the Spitzer Space Telescope from our solar system's vantage point for 350 hours between July 2011 and November 2015.

"Our observations suggest that our understanding of planet-star interactions is incomplete," said de Wit. "There's more to learn from studying stars in systems like this one and listening for the stories they tell through their 'heartbeats.'"

Because of the system's alignment with respect to Earth, Spitzer was able to observe the planet cross directly in front of the star (in a process called a "transit") as well as behind it (called a "secondary eclipse"). These eclipses of the planet allowed scientists to determine that the pulsations originate from the star, not the planet. The point of closest approach occurs between the transit and secondary eclipse.

Calculations by co-author Jim Fuller, Caltech postdoctoral scholar, predicted that the pitter-patter of the star's vibrations should be quieter and at a lower frequency than what Spitzer found.

"Our observations suggest that our understanding of planet-star interactions is incomplete," said de Wit. "There's more to learn from studying stars in systems like this one and listening for the stories they tell through their 'heartbeats," as quoted by a NASA statement.