Eta Carinae, one of the brightest known stars in the Milky Way galaxy went through some tumultuous times over the last two centuries, colliding with neighbours, eating other stars and so on. During this time, about 170 years ago, Eta Carinae erupted, unleashing almost as much energy as a standard supernova explosion.

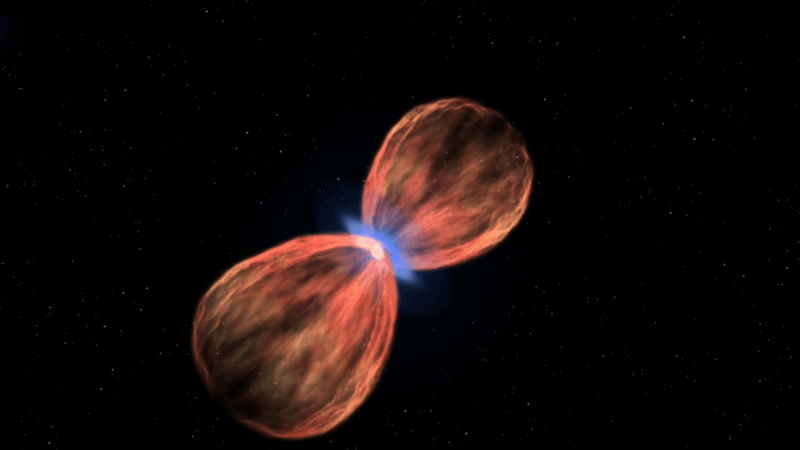

That powerful explosion, however, wasn't really enough to obliterate Eta Carinae, it is still there, visible as a dumbbell-shaped binary star and astronomers are yet to fully explain, or even understand and explain the explosion.

NASA's Hubble site explains that though it is not possible to travel back to the 1800s to once again see and record the actual eruption, a "rebroadcast" of sorts was captured by scientists, about 170 years later, now. This was made possible by light reflecting off interstellar dust clouds and reaching Earth only now. The same light from the original explosion. This effect is called a light echo, notes Hubble site.

New measurements from the 19th-century eruption, were reportedly made by ground-based telescopes, and they have revealed that material from the explosion has been expanding with record-breaking speeds of up to 20 times faster than astronomers first believed. These velocities, notes the report, are similar to what is seen as the fastest materials ejected by a supernova, rather than soft winds that usually come from massive stars as they die.

Astronomers studying this new data found that the eruption recorded in the 1840s might have been triggered by a long-standing stellar feud among three sibling stars. This battle ended up completely obliterating one of the stars and left one massive star and one small star orbiting it.

As for the explosion itself, it spewed material more than 10 times the mass of the Sun into space. This ejected mass left two gigantic polar lobes that resemble the iconic dumbbell shape seen in today.

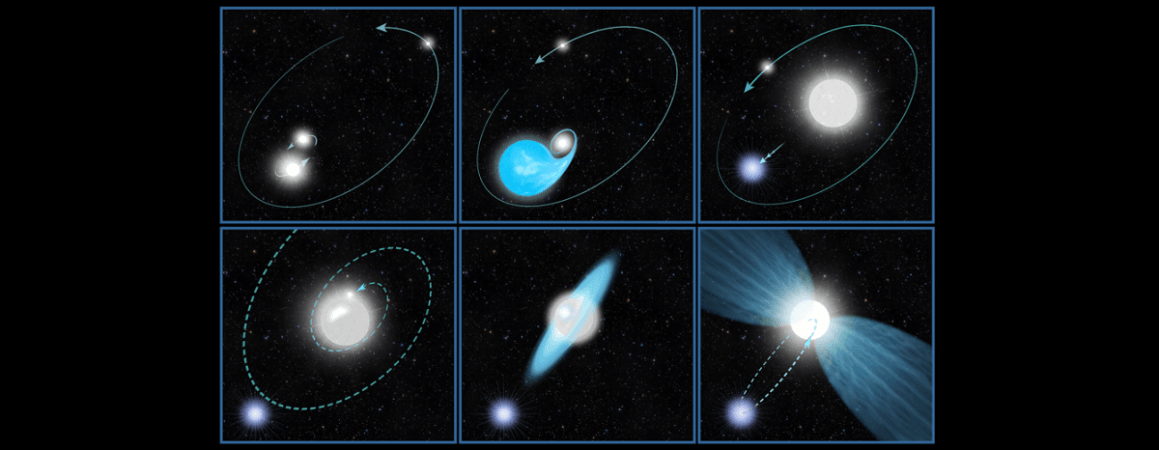

Eta Carinae, when it first started off, possibly billions of years of ago, was a triple-star system, says the report. It was two large stars orbiting close to each other and a third one orbiting them much farther away. One of the close two stars, the bigger one, started to enter the end of its life, it started to expand and starts feeding material into its closest companion. All this excess material bulks up the sibling, causing it to become extra bright. This donor star, now having lost most of its mass, begins to drift farther away from its now monster sibling. Moving away from the larger sibling, it starts to interact with the outer star, the small one with the oblique orbit.

During this interaction, the outer star and the dwindled inner star trade places, and this movement causes the original outer star to fall inward, so close that it actually hits the monster star and they merge and explode, it is this explosion that astronomers in the 1840s saw. The surviving companion star, the original large star, which is now small and weak, continues on its elongated orbit around the merged pair. It was found to pass through the monster star's outer gaseous envelope every 5.5 years.