Alien life could be hiding in the Solar System and it could be just below the surface of one of Jupiter's moons- Europa. In fact, one needn't look too far for it, about a centimetre below the icy surface, life might just be there.

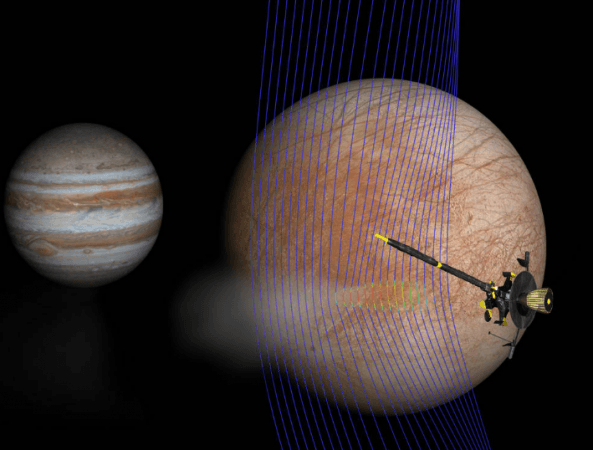

Europa is a large icy moon and for a long time been one of the places that scientists believed might just harbour life—apart from Mars, Enceladus, and a few other spots within the confines of the Solar System. NASA's Galileo mission discovered that Europa might have a massive global ocean right below underneath its frozen shell. Since the 90s, astronomers have been wondering just how its capacity for having actual water-based life would be or at least just biosignatures that mean it was, at some time in the past, habitable.

The moon, however, has rather harsh climatic conditions, so actually landing and looking for life might be near impossible and the surface of Europa might just be impenetrable, or so it was believed.

A new study says that amino acids that make up proteins and seen as signatures of life could actually survive millions of years on moon's surface. Even intense radiation that Europa gets bombarded with is unlikely to kill these amino acids off.

What bout the radiation then?

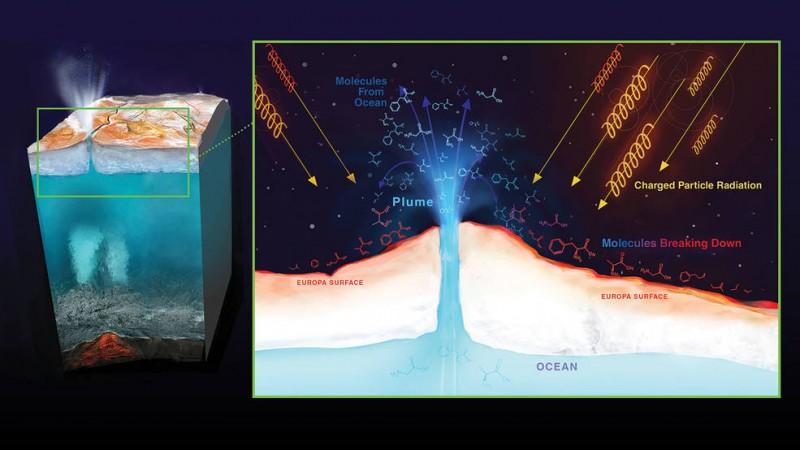

Tom Nordheim, lead study author and NASA scientist explains- "If we want to understand what's going on at the surface of Europa and how that links to the ocean underneath, we need to understand the radiation. ..Does this tell us what is in the ocean, or is this what happened to the materials after they have been radiated?"

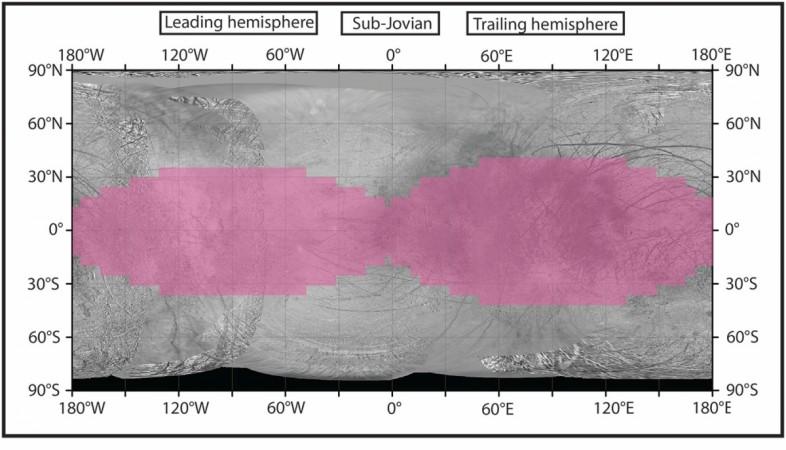

The team created detailed maps of Europa and used data from past missions- going as far back as the Voyagers. Findings suggest that half of Europa's surface filled with harsh radiation. These zones were also found to be shaped like ovals that attach to one another at their end points. That puts the equatorial regions in the high-intensity zone and the poles receive much less radiation in comparison.

High-intensity radiation zones only go 10cm to 20cm deep into the surface ice.

"Even in the harshest radiation zones on Europa, you really don't have to do more than scratch beneath the surface to find material that isn't heavily modified or damaged by radiation," said Nordheim.

Europa is the smallest of Jupiter's four Galilean moons and landing on it and obtaining samples, is no simple task. The icy shell that makes up the surface of Europa is about 20 km thick. To get samples of the water below its surface requires enormous drilling equipment to be sent from Earth, over 620 million km.

A much better, more practical option would be to launch a lander to the moon. Because of its proximity to its parent planet Jupiter, the moon undergoes intense geological activity and is known to regularly "outgas" water from the internal global ocean. They look like massive geysers and these spots could provide samples that can be studied in situ.

NASA is already preparing for such a mission, said some media reports. While not exactly a lander, scientists are working on an orbiter called the Europa Clipper. It will be performing close flybys of Europa, 45 times in all, and study the plumes that get ejected from the moon.

The mission is set to launch in the 2020s. While these plans are already in motion, NASA is already working on a follow-up to the Clipper- this time a lander.