NASA has reportedly discovered a chemical called acrylonitrile in the atmosphere of Saturn's biggest moon Titan.

ALSO READ: Scientists spot a mysterious object beyond Neptune [VIDEO]

Acrylonitrile (CH2CHCN) is also known as vinyl cyanide, which is used in the production of plastics. According to scientists, under the harsh conditions that Titan prevails in, this chemical is estimated to be able to form stable and flexible structures which would be similar to cell membranes.

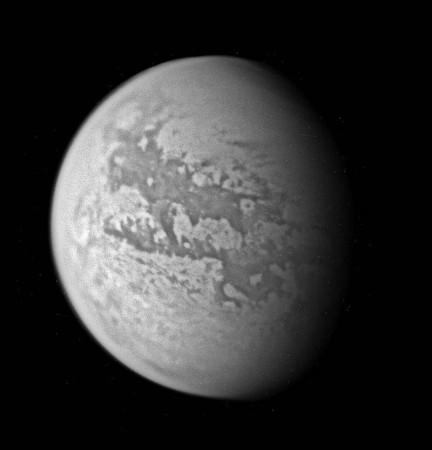

It was previously suggested by the researchers that acrylonitrile is one of the components of Titan's atmosphere. They did not report any exact detection of this chemical in the variety of organic or carbon-rich molecules found on the brownish-orange coloured moon.

NASA researchers found the chemical fingerprint of acrylonitrile in the data collected by Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. Huge amounts of this chemical were found on Titan by the researchers probably in the stratosphere of the moon.

"We found convincing evidence that acrylonitrile is present in Titan's atmosphere, and we think a significant supply of this raw material reaches the surface," said Maureen Palmer, a researcher with the Goddard Center for Astrobiology at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Titan's surface temperature is minus 179 degrees Celsius (minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit along with lakes comprising of liquid methane, which makes it difficult for the plants and animals existing on Earth to survive.

It was in 2015, university scientists found out whether any organic molecules could exist in any inhabitable conditions and form structures of lipid bilayers of living cells on Earth, a NASA statement revealed. The main component of the thin and flexible cell membrane is the lipid bilayer which separates the inside of the cell from the outside world and acrylonitrile as the best candidate was found to be the best candidate.

Acrylonitrile molecules were found to act as a sheet of material that was similar to a cell membrane, which could form a hollow microscopic sphere termed – azotosome -- the researchers anticipated. This could act as a tiny storage and transport container similar to the ones formed by lipid bilayers.

"The ability to form a stable membrane to separate the internal environment from the external one is important because it provides a means to contain chemicals long enough to allow them to interact," said Michael Mumma, director of the Goddard Center for Astrobiology, which is funded by the NASA Astrobiology Institute. "If membrane-like structures could be formed by vinyl cyanide, it would be an important step on the pathway to life on Saturn's moon Titan."

Acrylonitrile was found in abundance in Titan's atmosphere by the Goddard team, it was found to be present at concentrations up to 2.8 parts per billion. The moon's stratosphere was found to be rich in this chemical, at altitudes of around 200 kilometres (125 miles). The chemical eventually makes its way to the cold lower atmosphere, where it condenses and rains on the surface.

Astronomers calculated the amount of the material could be deposited in Titan's second-largest lake -- Ligeia Mare -- that occupies roughly the same surface area as Earth's Lake Huron and Lake Michigan together. Over the lifetime of Titan, the team estimated, Ligeia Mare could have accumulated enough acrylonitrile to form about 10 million azotosomes in every millilitre, or quarter-teaspoon, of liquid. That's compared to roughly a million bacteria per millilitre of coastal ocean water on Earth.

The key to detecting Titan's acrylonitrile was to combine 11 high-resolution data sets from ALMA. The team retrieved them from an archive of observations originally intended to calibrate the amount of light being received by the telescope array.

In the combined data set, Palmer and her colleagues identified three spectral lines that match the acrylonitrile fingerprint. This finding comes a decade after other researchers inferred the presence of acrylonitrile from observations made by the mass spectrometer on NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

"The detection of this elusive, astrobiologically relevant chemical is exciting for scientists who are eager to determine if life could develop on icy worlds such as Titan," said Goddard scientist Martin Cordiner, senior author on the paper. "This finding adds an important piece to our understanding of the chemical complexity of the solar system."

Watch video: