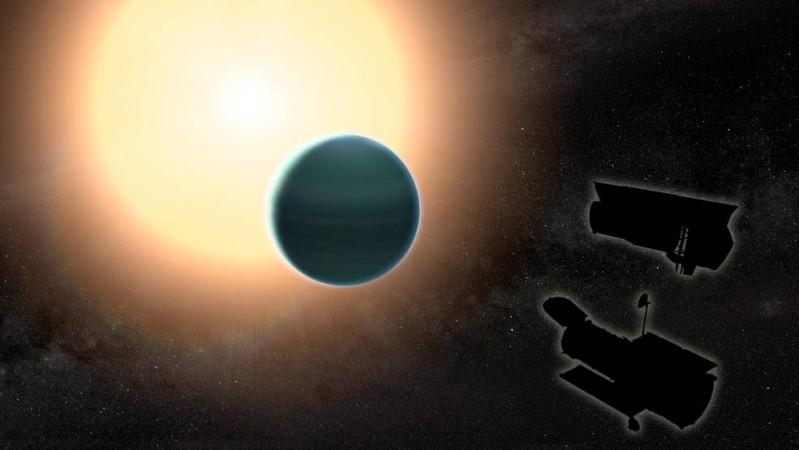

A recent study carried out with the help of NASA's Hubble and Spitzer telescopes have discovered a distant Neptune-sized planet -- HAT-P-26b -- which comprises of a primitive atmosphere comprising entirely of hydrogen and helium.

Also Read: Meet China's newly-identified dragon Baby Louie [Video]

The exoplanet is located 437-light-years away from Earth and orbits a star which is almost twice as old as Sun.

This is one of the most detailed observations of an exoplanet which is also referred to as "warm Neptune" as it is a Neptune-sized planet orbiting its star closely, while completing its orbit in a span of 4.23 days.

This planet is not a water world, but findings reveal that its atmosphere doesn't comprise of clouds and has strong water signature.

As per the team of astronomers, this is the best measurement of water made so far on a planet of this size.

"Astronomers have just begun to investigate the atmospheres of these distant Neptune-mass planets, and almost right away, we found an example that goes against the trend in our solar system," said Hannah Wakeford, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the study published in the May 12 issue of Science.

"This kind of unexpected result is why I really love exploring the atmospheres of alien planets," she added.

The researchers analysed the atmosphere of HAT-P-26b using its transits, ie, when it passes by its host star. During the transit period of the planet, a part of its parent star's light filters through its atmosphere and it can be seen clearly. During the transit period, some of the wavelengths of light of the host star are also absorbed by the planet's atmosphere while others are not. By assessing the alterations in the starlight due to this filtering, the astronomers can find out the chemical composition of the planet's atmosphere.

In this study, the researchers accumulated the data from four transits of the exoplanet which were measured by Hubble and two of which were observed by Spitzer.

"To have so much information about a warm Neptune is still rare, so analyzing these data sets simultaneously is an achievement in and of itself," said co-author Tiffany Kataria of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

As the research provided an accurate measurement of water, the astronomers were able to approximate the exoplanet's metallicity by using the water signature. This pointed towards how rich the planet is in elements which are heavier than hydrogen and helium. It also helped in providing evidence about the formation of the planet.

The metallicities of planets are compared using Sun as a reference point. Jupiter has a metallicity of around two to five times that of the Sun, whereas Saturn's metallicity is 10 times than that of Sun. The low metallicity values of these planets point towards the fact that they majorly comprise of hydrogen and helium.

On the other hand, ice giants such as Neptune and Uranus are comparatively smaller than the gas-giants, but they possesses higher amounts of heavier elements and have metallicities equal to around a hundred times than that of Sun. This leads to the conclusion that bigger planets have lesser metallicities.

According to scientists, the reason behind Neptune and Uranus being high in metallicities is that they originated in an area located towards the outskirts of the massive disk comprising debris and gas which swirled around Sun where these planets probably collided with a number of icy debris which were rich in heavier elements.

"Two planets beyond our solar system also fit this trend. One is the Neptune-mass planet HAT-P-11b. The other is WASP-43b, a gas giant twice as massive as Jupiter. But Wakeford and her colleagues found that HAT-P-26b bucks the trend. They determined its metallicity is only about 4.8 times that of the sun, much closer to the value for Jupiter than for Neptune," a NASA statement said.

"This analysis shows that there is a lot more diversity in the atmospheres of these exoplanets than we were expecting, which is providing insight into how planets can form and evolve differently than in our solar system," said David K Sing of the University of Exeter and the second author of the paper.

"I would say that has been a theme in the studies of exoplanets: Researchers keep finding surprising diversity," Sing concluded.