Researchers now reckon that our galaxy is present in a giant cosmic void, which is around one billion light-years wide.

Also Read: Boomerang Nebula: Mystery behind Universe's coldest object solved!

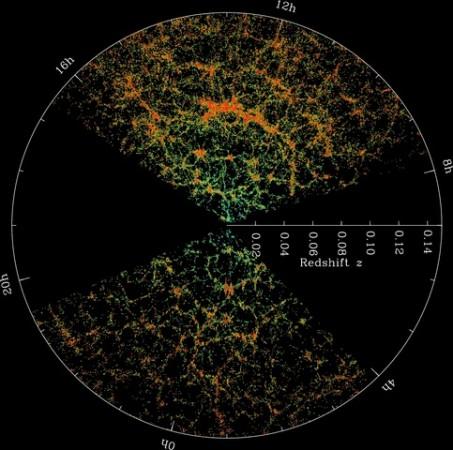

In 2013, researcher Amy Barger along with her then-student Ryan Keenan had found that our galaxy is present in an enormous void – which refers to a comparatively sparse region of space which contains fewer galaxies, planets and stars than expected.

According to the hypothesis of the researchers, the hole in which our galaxy is present is 1 billion light-years across, ie, seven times bigger than an average void should be.

On June 7, the findings of this research were presented at the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

This study was conducted by physicists with Benjamin Hoscheit as the lead author. It was found that the void containing the Milky Way is enormous, spherical and contains many superclusters.

"No matter what technique you use, you should get the same value for the expansion rate of the universe today," Ben Hoscheit, elucidated.

"Fortunately, living in a void helps resolve this tension," Hoscheit added.

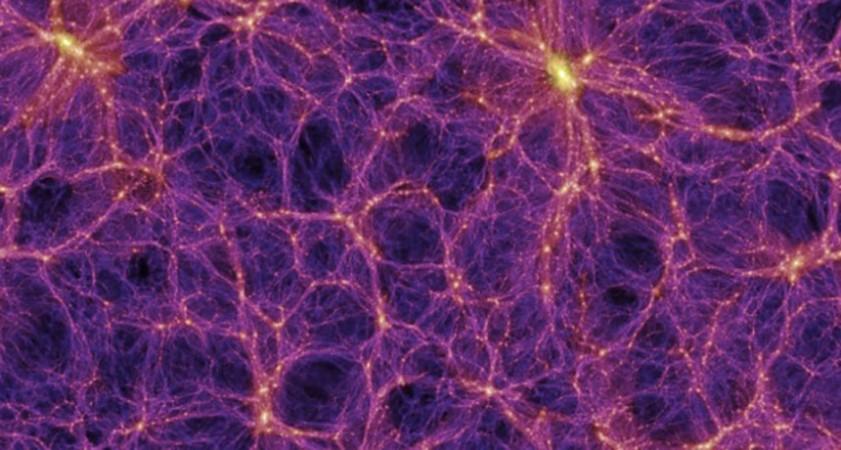

The new study not only firms up the idea that we exist in one of the holes of the Swiss cheese structure of the cosmos, but sheds light on how we measure the expansion rate of the universe.

The study explained that the region outside the void has way more matter which exerts a larger gravitational pull.

The researchers use various methods to calculate the expansion of the Universe. One of the ways is known as Hubble Constant – a unit used to describe the universe's expansion rate.

The bright light from a supernova explosion, where the distance to the galaxy that hosts the supernova is well established, is the "candle" of choice for astronomers measuring the accelerated expansion of the universe. Because those objects are relatively close to the Milky Way and because no matter where they explode in the observable universe, they do so with the same amount of energy, it provides a way to measure the Hubble Constant.

Another method used by the researchers to measure the expansion of the Universe is -- Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) – which refers to the light leftover from the Big Bang.

"Photons from the CMB encode a baby picture of the very early universe," Hoscheit explained.

"They show us that at that stage, the universe was surprisingly homogeneous. It was a hot, dense soup of photons, electrons and protons, showing only minute temperature differences across the sky. But, in fact, those tiny temperature differences are exactly what allow us to infer the Hubble Constant through this cosmic technique."

"It is often really hard to find consistent solutions between many different observations," said Professor Amy Barger, a University of Wisconsin–Madison astronomer.

"What Ben has shown is that the density profile previously measured is consistent with cosmological observables. One always wants to find consistency, or else there is a problem somewhere that needs to be resolved."