There is a lot more to Nagaland than the Hornbill festival or erstwhile fierce tribes. A beautiful land of mountains and forests, and a friendly people whose kings live like commoners, this is a part of the country still caught between the past and present. Water from the hills, food from the fields, cargo pants from the world outside, and prayers in the church.

A tour of some remote parts of Nagaland can best be described as a time travel into the past. Yes, when 5G and smart cities are the buzzword elsewhere in the nation, in this part of the north-east, time does a slo-mo.

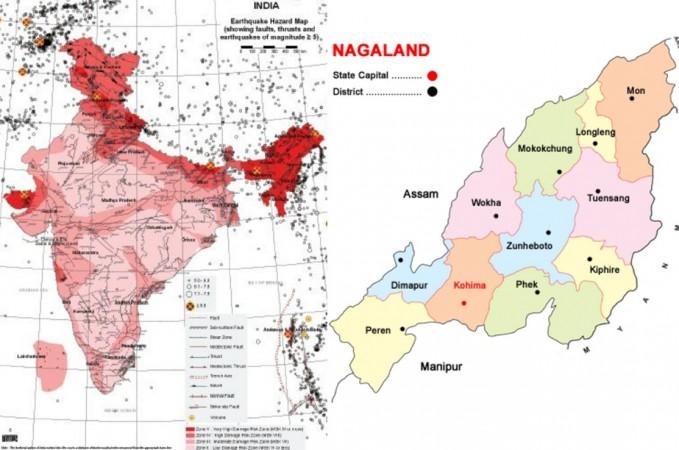

As part of a travel recce, we passed through a few villages in the north-eastern district of Mon that shares boundary and a village with Myanmar! From there we went to Longleng and Mokokchung districts and onwards to Wokha, covering around 20 villages en route.

People in most of these places live in bamboo mat huts, bound by wooden logs and plastic sheets. Toilets located well away from the houses have to be accessed at one's peril. Scorpions and snakes are co-habitants. Water is collected from streams running down hill slopes, using sliced bamboo pipes. Power lines have reached most places but power cuts are the norm.

The Naga folks here are dependent on firewood for cooking. Residents leave home early morning to go work in the fields and return late at dusk with the basket on their back laden with wood collected from the forests. As a result, empty streets greet one in most villages, like Shangnyu or Zangkham in Mon, with a few young children playing by themselves. Local primary or secondary schools are the only places one can find anyone during the day.

The roads are a nightmare in some places. Occasional tempo vans move to and fro bringing some essentials like salt, sugar, etc.

Ironically, almost all these places are well serviced by Airtel or Jio.

Scenic paradise

A land of mountains and jungles, Nagaland is a feast for the eyes. Green and blue hill slopes stretch into the horizon, waterfalls dot the landscape, sub-tropical forests thick with young bamboo and wild banana interspersed with the vegetation, mountain tops claimed by cluster of houses - their tin roofs glinting in the sunlight, a river here and there winding its way around the foothills, a Naga native trudging up a slope with his/her back weighed down by the firewood load, and a silence, broken now and then only by the cicadas.

We were the first tourists or outsiders that people were seeing in some of the villages. The whole village would arrive on the spot as we saw at Sakshi in Longleng district. Besides a handful residents who know a smattering of Hindi or English, people converse in Nagamese. Smiles spoke where dialect failed.

Most villages do have schools, and most children are schooled, but language proficiency in English or Hindi is poor. Perhaps the language issue is why most youth do not venture out in search of jobs. But Nokven, a substitute teacher at a local private school in Zankham, thinks "when we earn the same amount outside as we can at home here, why not stay and serve your people?"

Abraham from Wangla, in northern Mon, has worked in a hotel in Kerala and returned home during the Covid lockdown. He plans to take up work soon.

Often to reach a place and take up a job, the Nagas lack money. As Yanghat, a teacher at Nyasa village in Mon noted, the fare for transportation cannot be afforded. But there are quite a few who have ventured out and these are mostly working in the food industry. At Zangkham, friends of Nokven who have done their hospitality studies at Guwahati are working in metros like Mumbai and Chennai.

Where Kings still live

The Konyaks especially are very bitter about lack of jobs and believe that they are side-lined in government jobs. Lack of adequate representation in the state cabinet is cited as a reason. Konyaks are among the 16 recognised tribes that make up the Naga population. They inhabit the eastern parts of the state and owe their allegiance to the king or 'Ang'. Among other tribes, it is the GB or the Gao Bura (village head) whose word is diktat as far as customs are concerned. It is the Village Council that takes up all development issues everywhere.

As the pastor Jakmeth at Pongkong village said, the eastern side of the state is less developed compared to the western part and that is a main reason the region has been asking for separate statehood. His wife, a retired nurse, now goes to pluck tea leaves for Rs 200 a day!

So also, in the Phom-tribe dominated Tamlu village in Longleng, a village council member pointed to unemployment among the youth. "We do not have the money needed to buy us the government jobs. As a result our youth are here in the village, rolling betel leaves that are packed and sold in the cities of nearby Assam."

Doc in domicile

There are the occasional cases like Dr Chingei Phom of Sakshi village in Longleng district who studied in neighbouring Manipur and came back to his village to serve the residents. A covid vaccination camp was on at the village for booster doses. So also at Yongnyah, the biggest Phom tribe village, the doctor at the primary health centre is one of the locals who studied outside and came back to serve the people.

Is there poverty? It depends on how one defines the term. If it is about feeding the stomach, there is enough and at times a bit more, which finds its way to the nearest town. In an ironic impasse, without money people cannot afford to send children for higher studies and without jobs there is no way money can flow into the villages. Even the excess vegetable produce cannot be shipped out due to bad roads. As Chempal, the student union general secretary at Zangkham said, the situation gets worse with no bank or money to buy and sell produce to each other too.

Greed is yet to reach these parts.

Farmers and artists

Water is scarce in some places. Some villages have a tank set up to distribute the water to the homes but pipelines are still being set up in many places. For many, water has to be fetched in buckets.

Farming is the mainstay with people growing what they need for their families. Jhum (or shifting) cultivation is mostly practised in these parts. Sections of the forest are cleared and burnt, with the ashes used to provide nutrients for the next set of crops. Once harvested in a few months, the land is left to regenerate with natural vegetation while adjacent areas are cleared for cultivation.

Most Naga farmers like Bauting, the head GB at Nian village, will tell you proudly that their products are chemical free. Besides rice, corn and vegetables like cucumber, yam, brinjals and beans, they also cultivate fruits like banana, pineapple, pears, etc. King chilli, ginger, soya, betel leaves and arecanut are also grown. In some areas, cardamom and rubber are also grown on experimental basis. Dry cultivation of rice and yam can be seen on some of the slopes.

Surprisingly, we came to know that a caste system is prevalent in some villages and marriages across castes are not generally permitted. The Kings in some villages have more than one wife. In many cases this is so because of want of a suitor. Women born to the royal couple are allowed to be married only to kings or princes and when there is a dearth of such suitors, they may end up being married to a king who has more than one wife and is double their age.

Art and craft are a part of people's lives in Nagaland. It does not require the annual festivals like Aoliyang or Monlieu to showcase this. From modas (small seaters) to baskets to mats, it takes an average craftsman between 3-6 days to weave artifacts of beauty. At Shangnyu village, an old woman over 80 was calmly beading a necklace. With the thread wound around her feet she patiently picked bead after bead and wove it in, meditatively. A smile thrown at the strangers and some unfamiliar words, she continued her activity.

Most homes display art on paper by the residents. Displaying the range of home-spun jewellery from head band to neckpiece and waist band, all done in orange beads, a resident farmer at Shangnyu told us that it was the equivalent of an heirloom passed from father to son.

Medical lacunae

Many villages with over 2,000 residents do not have adequate medical facilities. At Zangkham in Mon district, with over 5,000 residents, there is only a dispensary but no doctor. A pharmacist or 'compounder' usually doles out the medicines.

According to Dr Sahshoor from Hans Foundation whose mobile van visits some of the villages on a monthly basis, many areas have residents with tuberculosis. During our visit too, we did see many residents with racking cough – most likely from a combination of poorly ventilated rooms and constant smoke from the burning of wood for cooking. Like everything else, they take it in their stride.

The need for medical aid was clear in the line-up at Chingphoi village (Mon) housing around 615 people. With no clinic or doctor, the monthly visit is much awaited. According to the doctor, many residents of these villages ail from high BP and blood sugar, the latter owing mostly to a carbohydrate heavy diet. Joint pains are common complaints, given a poor calcium diet and rigors of trudging up and down the slopes lugging wood and farm produce on their backs. The pervasive paan chewing has also led to poor dental health, according to the doctor. The people are charged Rs 10 for consultation and given medicines at half the price.

Sadly, not all villages have the facility available.

The most commonly heard demand was for roads and ATMs. With most villages lacking a bank or ATM, it requires travel for hours by vehicle or foot to the nearest town just to get some money. For Zangkham village, the nearest town is Tizit at 40 kms but the road is in a bad shape and getting provisions calls for a long trek. The village is all expectation now, as the road is almost ready.

Interestingly the state does not have a railway line to its capital city Kohima. The first phase of connecting Dimapur (on the border with Assam) to Kohima through a broad gauge line has just been completed.

Village guards

In most villages we went to, we were invariably first met by a posse of 'village guards' dressed in khaki. Village Guards are the equivalent of cops stationed in the villages. Drawn from the villages they guard, their job is much like the police to ensure peace and control any conflict situation. In the Konyak regions, a guard always accompanies the king and prince.

With a tough schedule that stretches from 6-6 with day and night shifts, the village guards are a poorly paid lot. Salaries of Rs 3000 a month are a pittance, given that they are equivalent of home guards who are paid 15k, noted the Commander in a village. The GBs or Gao Buras are also supposed to be paid by the government, but hardly get any regular salary. Sometimes, they receive a lump sum at the end of the year, we were told.

Hygiene

Villages are clean with no garbage seen. The plastic invasion is still in its infancy though the small village shops do sport some of the junk food that come in plastic covers and end up in the village bins. Anything that cannot be reused is burnt and the rest is used. Plastic covers are not thrown but saved and kept to be reused.

But as one approaches any town, the use and throw culture is evident in the waste dumped on hill slopes or flicked into the river most casually. Most villages are open-defecation free.

Around the hearth

A typical house in the north and eastern districts of Nagaland revolves around the kitchen, or rather the hearth. It is the first room one enters and all gatherings happen here. The fire is most always burning and visitors can be seen sharing a cup of black tea any time of the day.

Around the hearth and mounted high on the walls like trophies are the heads of the animals that were hunted. Hung lose around the fireplace are tails of cats, squirrels, deer, etc. Sometimes you can even chance upon a tiger or python skin, hunted and killed by one of the forefathers. There are no tigers recorded in Nagaland today.

Hunting is a tradition and most men when stepping out carry a rifle, manufactured locally. Ask them and they will tell you it is for protection from wild animals that they carry the rifle, but it is an open secret that the locals need their wild meat as part of their menu. The staple diet is rice and dal thrice a day, along with some boiled vegetables like brinjals, yam, bamboo shoot, beans, etc accompanied by chicken or pork. Cicadas, maggots, flies, frogs and insects add to the variety.

Fishing is practised by blocking the stream with bamboo leaves and branches to create a dam-like structure and then hand-made bombs are thrown into the water. The fish are all killed and netted.

Things are slowly changing with the new generation and education. Pangti, a village in Wokah dt, close to the Doyang reservoir had been in the news for the wrong reasons - hunting of the migratory Amur Falcon birds in large numbers, first reported in 2012. Luckily, thanks to the work by conservationists who involved the locals in the job, the hunters were turned into protectors. The dam here over the river Doyang, a tributary of Brahmaputra, has become the chosen spot by millions of the birds en route from Russia and China to South Africa in a journey spanning 22,000 kms. Pangti is now called Amur Falcon Capital.

Say No to drugs

Speak of drugs or the 'underground' (the separatists) and the conversation will become a monologue. Said to have been introduced by the British a century ago, to win over the fierce Konyak tribes, drugs have latched on to the Naga society, especially the youth. Sharing a border with Myanmar which is the second largest illegal opium seller, the situation was further compounded in the years that followed.

Huge billboards put up by the authorities caution people on drug use. As to the 'underground', the locals will brush it off. One of the teachers at a village referred to the militants as "just another political faction, out to divide and create unrest." A few days after we had passed the army unit posted at Nyasa village in Mon, there was an attack on the unit, resulting in casualties on both sides.

The Nagas are a friendly and welcoming lot. In the span of two weeks, we did not chance upon a single fight or argument anywhere. They are generous at heart, like the farmer who returning home with his produce, quickly removed two fresh cucumbers and offered them to us. Their welcome of the first 'tourists' to their village was nothing short of lavish, and meals replete with a hen or pig led to the altar.

Since the advent of Christianity a 100 and more years ago, the tribes have shed their traditions along with their costumes. Most of the youth wear T-shirts (for some reason, rolled up to the chest!) and shorts or pants. A majority are Baptist Christians while you can also find some Catholics. The Sunday sabbath is strictly followed and any tourist who lands in any of Nagaland's towns on a Sunday will have a tough time finding a place to stay, forget anything to eat. All establishments are shut down on Sunday, as we learnt the hard way before ending up cooking at one of the roadside shelters.

The youth sing carols and English songs, while some elders still remember old lores and customs as we saw at Amosen village (Longleng). Practising any of the traditions is advised against by the priests, but centuries-old traditions take long to die.

From animism to Christianity

For instance, at Longkhum, in Mokukchung dt the belief is that the spirits of the dead rest a while here, before leaving to heaven. Known for its 'headhunters', (the king's soldiers who were decorated with tattoos according to the number of enemy heads they beheaded), the Ao tribe here believe the eagles are manifestations of the dead. One of the tourist spots shown is a distant cave used by eagles. A 'stone bridge' made of a ridge of stones extends for a few hundred metres through the rhododendron woods to a spot where water coming down the hill is collected and consumed as 'magical healing water'.

At a village in Wokah, the chairman showed us magical stones which were once worshipped "and would go dancing all around the place. If there was no rain, we would turn them over and it would rain. Now we don't worship them and they don't dance."

Go to any village like Lotsu and you can see huge stones lying discarded on the grounds. These were once memorial stones erected for warriors on their graves or tombstones. Now they lie strewn around, staring at the sky like forlorn relics of a bygone time.