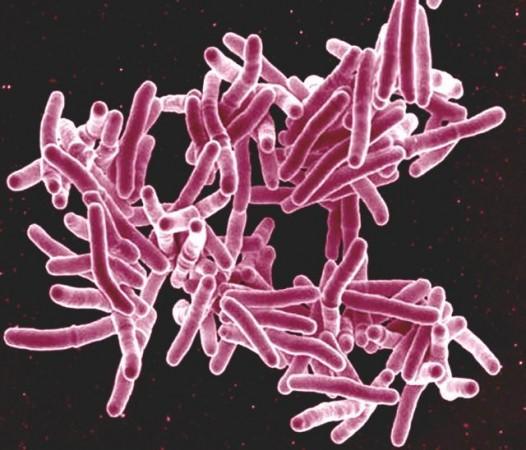

Among the life-threatening bacterial diseases in existence, tuberculosis (TB) is among the worst. It is a highly contagious infection that mostly affects the lungs and is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) bacterium. How the immune system responds to the illness dictates its progression. Now, scientists have discovered that Mtb can make an individual's immune cells lower their immune defenses against it.

In a new study, researchers from the University of Maryland identified a specific gene, PknF, in the bacterium that suppresses the immune actions of infected human cells. It does so by limiting the response of protein complex known as inflammasome—a component of the body's innate immune system—within the host cells; ultimately leading to the worsening of the infection. The research was published in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

"This is exciting that we have discovered an interaction that has never been observed before between the bacteria that causes tuberculosis and a signaling system in human cells that is important in the cell's defense against pathogens," said Dr. Volker Briken, senior of the study, in a statement.

An Infectious Killer

While modern medicine has made the treatment of TB easier, the infection continues to kill thousands of people daily. According to the WHO, the sickness claims approximately 4000 lives every day worldwide. The Global TB Report 2020 by the international body found that around 10 million contracted the disease in 2019, while about 1.4 million people lost their lives due to it. Therefore, it continues to be one of the most lethal infectious killers in existence.

TB spreads from an infected individual to a healthy one through tiny droplets expelled in the air through sneezes and coughs. Though TB predominantly affects the lungs, it can attack other parts of the body such as the brain, spine, and kidney. Not all those who harbor the pathogen get sick. Therefore, the disease is categorized into two forms—Latent TB and Active TB. In Latent TB, the bacterium is not active in the body and the individual is not contagious. However, it can become active. As the name suggests, Active TB is where the individual is sick and can spread it to others.

Some of the common symptoms of the infection include persistent cough for over three weeks with mucous or blood, fatigue, weight loss, chills, and loss of appetite, among others. The symptoms may vary depending on the organ affected. While a long course of multiple medications can help in recovery, the emergence of Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) serves as a cause of worry. People with diabetes or malnutrition, users of tobacco, and individuals with compromised immune systems such as those with HIV, are at a greater risk of infection.

Restricting Immune Responses

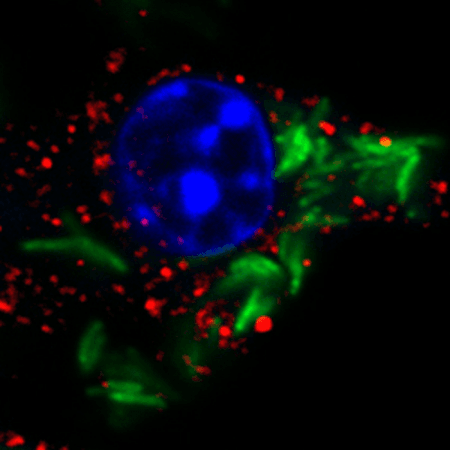

For the study, the authors infected macrophages—a type of white blood cell—with either a non-virulent bacterium or Mtb. The responses of the cells were analyzed. It was found that an inflammasome known as NLRP3 was drastically reduced in cells that had been infected with Mtb. However, no such limiting of NLRP3 was found in cells infected with non-virulent bacteria. Inflammasomes are protein complexes within the innate immune system—the body's first line of defense against pathogens—that are responsible for the triggering of inflammatory responses.

"It was very unexpected for us to find this primary observation that Mtb can actually inhibit the inflammasome. The infection also causes some minor activation of the inflammasome, and so no one bothered to look for a potential of Mtb to inhibit the process. It is a classic example of the tug of war between the pathogen wanting to suppress host immunity and the host cell sensing the pathogen to activate immune responses," explained Dr. Briken.

A Culprit Gene

Following this, the team tried to ascertain whether a particular gene of Mtb was responsible for the suppression of the inflammasome. Genes from Mtb were inserted within a non-virulent species of mycobacterium and the mutants were used to infect macrophages. The scientists discovered that infection caused by the non-virulent bacteria that carried an Mtb gene known as PknF restricted inflammasome responses in host cells.

"We don't know how this gene inhibits the inflammasome but the function of this gene is to regulate the production and/or secretions of lipids, so we think maybe the bacterium modifies lipid secretion in a way that influences the inflammasome. That is what we will be investigating in future studies," noted Dr. Briken.

While the authors aim to learn how PknF suppresses inflammasome in host cells, they also intend to glean the gene's role in the virulence of the infection. If it is found that suppression of the inflammasome lets Mtb be more virulent, the gene may serve as a potential target for the treatment of the disease in the future.