Japanese researchers have in a breakthrough grown mouse embryos for the first time in space on the International Space Station (ISS).

The team from the University of Yamanashi successfully developed a fertilised mouse egg into a blastocyst at the orbiting lab, The Japan News reported.

The blastocyst can be explained as the stage where the cells differentiate for the first time into inner cell mass cells that go on to become the foetus, and trophectoderm cells to later become the placenta.

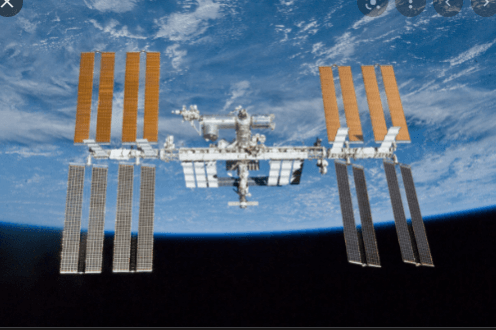

The research, published online in the journal iScience, revealed that 720 two-cell frozen mouse embryos were sent to the ISS, using a device developed by the team that also allowed astronauts to easily handle early mouse embryos.

The team thawed and cultured the embryos for four days.

Of the embryos, 360 were cultured in a device in the Japanese Kibo experiment module that generates 1G of gravity, the same amount felt on Earth. The remaining 360 were cultured in a zero-gravity setting.

The embryos were then fixed in formalin and sent back to Earth to be compared with embryos from a similar test on Earth.

Over 60 per cent of the embryos from the Earth test developed into blastocysts, while the rate stood at 29.5 per cent for the embryos in the 1G space test and 23.6 per cent for the zero-gravity test, the report said.

"We found that, even under zero-gravity conditions, embryos develop normally until they reach the blastocyst stage," Teruhiko Wakayama, professor at the University was quoted as saying by The Japan News.

"In the case of mammals, we need to examine whether they will implant and grow properly," Wakayama added.

The experiment found that the differentiations, rate of DNA damage and gene expressions of blastocysts developed in zero-gravity did not differ from those in other settings.

The research also found that the inner cell mass cells in three of the 12 blastocysts from the zero-gravity test examined in detail clustered in two places, instead of the usual one.

Such blastocysts have the possibility of developing into identical monozygotic twins, the report said.

(With inputs from IANS)