An islet cell transplant programme developed by a team of Canadian researchers is a safe, reliable and life-changing treatment for people with hard-to-control Type 1 diabetes.

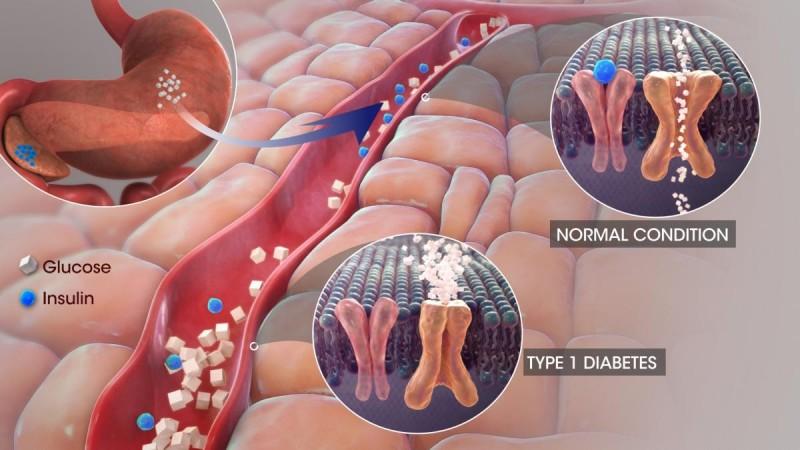

Islets are clusters of cells which produce insulin, a hormone that allows the body to control the flow of energy from food, storing the excess after meals and releasing it to allow the body to function between meals.

In Type 1 diabetes, the immune system mistakenly destroys the cells within islets so patients have to take insulin by injection. Patients with hard-to-control or "brittle" diabetes face life-threatening low or high blood sugars and long-term complications.

"We've shown very clearly that islet transplantation is an effective therapy for patients with difficult-to-control Type 1 diabetes," said James Shapiro, Professor of surgery at the University of Alberta. "This long-term safety data gives us confidence that we are doing the right thing."

"This data shows really strong proof that cell-based therapies can deliver a meaningful and transformative impact for people with diabetes," added Peter Senior, director of the Alberta Diabetes Institute at the varsity.

"We are delivering something which all other treatments for diabetes don't deliver -- there's a comfort, a predictability, a stability to blood sugar levels that don't exist with anything else."

In the study published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, the researchers report on patient survival, graft survival, insulin independence and protection from life-threatening low blood sugars for 255 patients who have received a total of more than 700 infusions of islets at the University of Alberta Hospital between March 1999 and October 2019.

The results showed that 70 per cent of the grafts survived for a median time of nearly six years, 79 per cent of the transplant recipients were able to stop taking insulin after two or more islet infusions and a median time of 95 days following the first transplant.

About 61 per cent were still insulin-independent a year later, 32 per cent at five years and eight per cent after 20 years, the researchers reported. While most patients had to resume taking insulin injections, the doses were usually much smaller than their original needs and their diabetes control was better.

"Being completely free of insulin is not the main goal," said Shapiro. "It's a big bonus, obviously, but the biggest goal for the patient - when their life has been incapacitated by wild, inadequate control of blood sugar and dangerous lows and highs - is being able to stabilise. It is transformational."