Making steel has been a good way of burning through money in the last few years, even on the positive tides of good domestic demand. But the pressure on debt-saddled Indian steel firms, who are on target to overtake Japan in a few years, is being aggravated by the rising squeeze on their operating margins, volatile raw material costs and inventory pile-ups. Another flank is now brought up by the banks who are focussed on resolving their stressed assets in the steel, infrastructure and cement sectors, instead of lending to new projects.

The slow progress on steel projects has crimped capital expenditure to a point where projects are getting stranded – a queer paradox when the 90-95 million tpa (tonnes per annum) industry is targeting capacities at 300 million tpa of steel by 2025-30.

The profits, when they do show up, are being expended on repaying bank debt or in fresh capex, while demand for finished steel has stayed relatively weak at 3 percent in 2016-17. A market where smaller, unorganised players, -- who often fashion steel products from scrap and the automobile aftermarket --, are posing stiff challenges to the established players and thinning down their profit margins, is as daunting to the banks as the prospect of their big steel borrowers running into debt traps, mostly inextricable.

As of March 2017, the gross non-performing advances ratio or bad loans ratio of banks stood at 9.6 per cent. This means that for every Rs 100 in loans lent by banks, Rs 9.6 was not being repaid by the borrowers. The top 12 accounts of banks, -- which, by no coincidence, comprise steel companies -- alone constitute a quarter of the gross non-performing assets (NPAs) marked down at Rs 8 trillion on their books.

These are the dozen companies referred by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for fast-track resolution under the new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC).

Protectionist vantage points

Domestic steel companies have been functioning on operating margins hit by lower prices and use of high-cost coking coal inventories. Unwinding 2-3 months of inventories will take time and costs which might hit EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) per tonne by 4-5 percent in the coming two quarters. Subdued domestic demand has been offset, only by attempts to increase export sales.

No meaningful respite is seen on the cost front, while India's steel production is quite on target. Steel prices for flat products declined by Rs 1,500-2,000 per tonne quarter-on-quarter to June this year, while long product prices increased by Rs 800-1,000 per tonne. In addition, export prices of hot rolled coil fell by Rs 4,000 a tonne quarter-on-quarter.

Domestic steel demand remains weak with 4 percent growth to 13.8 million tonnes in the April–May period of 2017. Uncertainty over GST implementation led to weak sales in the month of June 2017 as well. The demand has been particularly weak for long products due to subdued construction activity as offtake of bars, rods and structural products have been flat year-on-year at 6.9 million tonnes. Export sales have provided respite. India's consumption of total finished steel rose 4.6 per cent in the April-June 2017 period, aiding 4.6 percent growth in production for domestic steelmakers.

China, being the world's steel supplier, is in a position to impact steel supply and demand in the global market significantly. While steel prices were maintained at a steady peg throughout 2015, China's overcapacity riled the market, inhibited domestic demand and forced prices down in 2015. Goska Kafel, an analyst for research firm MarketLine, says, "China has been exporting its overcapacity below its costs to the rest of the world, adding pressure to other regions which also face overcapacity issues."

This led to a new wave of protectionism, where the enactment of tariffs and duties by other countries and regions could likely have the negative long-term impact of allowing protectionism to become the standard, which may allow inefficient steel producers to have a safe haven.

The rising protectionist trend against Chinese steel in India, has not helped revive domestic demand. But the same trend in other regions has helped boost India's steel exports to countries hit by rising domestic demand in the Chinese market since the beginning of 2017. This is to the Indian steel sector's advantage, but cannot be milked for long. The New Steel Policy 2017 investment target of Rs 10 lakh crore to realise capacity of 300 mtpa by 2030-31 must be embarked upon with caution, keeping in mind the overcapacity migraines which the Chinese faced.

Most steel companies have been heavily leveraged with there being a long period of increase in their working capital cycles, which were also led by inflation and the economic slowdown. Stranded projects, some of them dependent on costly imported LNG, have led to capex plans being stymied in the initial leg of the working cap cycle.

The government's reduction of import duty on LNG has revived demand marginally, though not adequately enough to justify capital expenditure targets. This implies that asset-heavy steel businesses which banks need for strong loan growth would be fairly subdued.

Subduing steel

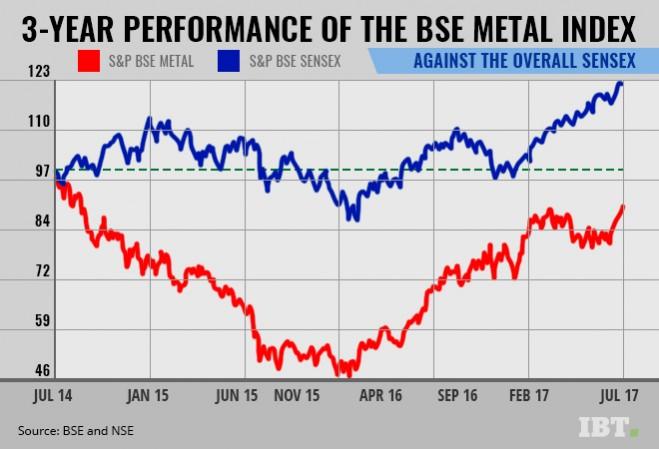

Cut to the state of high exports, high inventories, wafer-thin margins, falling price-to-earnings ratios and high debt at Big Steel: why were steel stocks going at such high prices for years on end? The only explanation is that investors were, against all odds, pretty enthused about the party raging on. But the mood has turned significantly downbeat as things turned serious quarter upon miserable quarter (see chart below).

The high default rate among the steel corporates has indeed compelled public banks to put a standstill clause to fresh demands for funds as a means to conserve capital, while reducing damage to their balance sheets in the medium term and addressing impairment-related issues.

Non-performing loans of banks have increased 55 percent since fiscal 2015, while risk-weighted assets (RWA) growth has been manageable at 2 percent, thanks to better capital utilisation by banks and a $4 billion capital infusion in 2016-17 by the government. A loan is categorised as a non-performing advance once repayment from the borrower is due for 90 days or more.

PSU banks have slowed down RWA growth to approximately 3 percent year-on-year compared to 5 percent in 2015-16, according to Kotak Capital, which expects a 6 to 37 percent quarter-on-quarter decline in consolidated EBITDA for steel companies due to lower operating margins and seasonally lower volumes.

There still appears to be no real consensus on the serviceable portion of steel debt or how banks will right-size this debt, and take huge haircuts, if necessary. Bank balance sheets could be battered further, if the steel companies go into liquidation, entailing steep haircuts of 80-90 per cent. Will this finally rid the steel sector of its debt overhang and resolve the NPA issue even partly?

There is still some room for targeted lending to promising projects even if the investment cycle and loan demand has slowed down in specific cases. But the watchword for banks will continue to be extreme caution; and, astute focus on recovering their investments -- without alienating their clients in the steel sector who, in a bid to raise capital, might diversify their credit base into commercial paper or non-convertible debt bonds. That wouldn't help the branding of banks as the beacon-lights of commerce.

Distressed debt needs to be addressed with a clear revival plan and shareholder interest in mind. For a start, a big part of corporate India needs to clean up its act, and urgently.