Around a decade ago, an India-based company called Datawind got a nod from the Central government to make and market a low-cost tablet PC called Aakash for students in the country. About half a decade before that — 2004, to be exact — the country launched GSAT-3 aka EDUSAT, its first satellite to be used entirely for the education sector.

Cut to the present, and it is more than two months since Datawind shut down permanently. Meanwhile, EDUSAT was deactivated in 2010, and has since been moved to a part of space that the world refers to as "graveyard orbit."

They were both examples of a political class thinking a little too ahead of time when it came to the technology needed for education. Something similar is now happening at the other end of the spectrum: While the world is agog about the latest iteration of the Raspberry Pi and an increasing number of people is adopting one or the other distro of Linux, most of India seems to be oblivious to both.

The current problem

The Datawind and EDUSAT examples are just two case studies of how India missed the education-technology bus, either by arriving too early for it or getting into the game too late. No such problem seems to be happening on the general technology front, with trials for 5G technology set to begin in India by mid-September this year.

Even otherwise, the country has been seeing a constant rise in the number of smartphones sold, even as data consumption rises with ever-cheaper tariffs. What's more, streaming and subscription services are also seeing a surge, even as e-commerce booms: Snapdeal managed to cut its losses more than 70 percent last quarter, and is expected to turn profitable within another year!

So where are we with technology in education? Students still have to buy desktops and laptops that cost at least Rs 20,000 and may have to shell out even more — well into the thousands — if they want licensed versions of the software.

The Raspberry Pi and Linux can solve both problems. The latest iteration of the Pi, while being extremely portable, is also cheap enough that it will cost a buyer less than Rs 10,000 — even below Rs 5,000 for one variant — with accessories, including a keyboard and a mouse. All people will need is a computer monitor, but a household TV may be used in its place. Distros of Linux, on the other hand, maybe the answer to the youngsters' need for a fully-fleshed Operating System (OS), and may also run on older PCs or laptops with lower computing capacity.

Why Raspberry Pi?

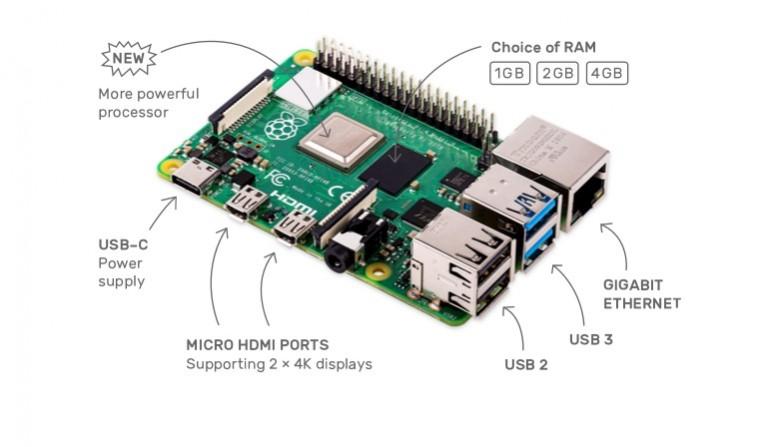

The Raspberry Pi is a System-on-Chip (SoC) based on the reduced instruction set computer (RISC), the kind that is often used in phones. Thus, everything from the processor to the RAM are attached to the board. As for size, it has the length and width of a credit card, and is only a couple of inches in tall at the highest point!

What's more, the latest version of the device, the Raspberry Pi 4 Model B+, now comes in three variants of LPDDR4 RAM: 1 GB, 2 GB and 4 GB. Bluetooth and Wi-Fi connectivity is built-in, while the entire device can be powered by a regular USB-C phone charger. And the best part of it is, the 1 GB version of the SoC is available in India at less than Rs 3,000 (taxes included) if you know the right place!

Then there's the software: Raspbian is a special version of Linux that runs on RISC machines without needing or blocking up too many resources. It can easily be used for basic desktop tasks, like creating documents, writing and sending emails, and even playing films — both offline and online. And it's free!

Add to that the basic peripherals and wires, and the entire setup, minus monitors, will cost you less than Rs 5,000. How do I know? I had the similarly priced Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ before I gave it to my niece to use!

The Raspberry Pi was designed with students in mind, which is why Raspbian lets users code in some of the most basic languages people will learn when it comes to programming. And yes, that includes Python.

Why Linux?

The case for Linux being used in education is queered by many factors, like generations of tech-illiterate or tech-averse teachers staying away from it, the OS being considered difficult to configure and work with, and the mostly-wrong reputation that Linux is a hacker's language.

While there may be some truth in the last statement, Linux has evolved over the years into an easy-to-use OS where everything you need to do is easily searchable, and that can be said for troubleshooting as well!

What's more, distros of Linux offer free software and open-source software that could rival even their best counterparts on Windows. In fact, software like VLC Player and LibreOffice were first developed for Linux before they made their way to the Windows platform.

Even better, there are versions of Linux that are so light on resource usage that they can run on computers that are nearly two decades old! This could be beneficial in multiple ways: It would ensure less expenditure on hardware, and less plastic waste if an old computer was kept functional instead of a new one being bought.

The deafening political silence

The reason I mention in this article is I believe they are key to an edutech revolution in India.

With the Central government on the verge of achieving full penetration of electrification, would it be too much to ask that each school in the country, government or otherwise, have computers to teach students? The answer should ideally be a resounding "no."

The question that now arises is, what to do with schools that do not have enough funds to buy computers do? The answer here lies with the UK-based Raspberry Pi Foundation and its SoC.

Now, Indians currently have to pay an export duty on the Raspberry Pi, but if the country can allow Apple to have a factory on its soil so iPhones can be cheaper, why can't it strike a deal with the Raspberry Pi Foundation to ensure its students get Pis that help them learn, and the foundation is suitably incentivised?

As for Linux, Kerala — the state with the highest literacy rate in India — seems to be showing the way. News broke in mid-May that the state government would deploy Linux in schools, saving it Rs 3,000 crore. However, not too many others seem to have shown any inclination towards going down the same road. And this, despite India already having a Linux distro made by a government agency and endorsed by the Central government itself!

Letting the coding revolution that is taking the world by storm pass by will one day come back to haunt India, and we will then have none but the lack of political will to blame for it as a new generation plays catch-up with the world.

(The author teaches journalism at St Joseph's College (Autonomous) in Bengaluru. The views expressed are personal)