It is possible to separate hydrogen from water to use as fuel in the future when humans travel deep space.

A team of scientists working on this project have published a paper where they have demonstrated how they harvested hydrogen from water in microgravity conditions -- similar to what is found in deep space.

Space travel, especially long-distance and by extension long-term, involves several difficult problems. These are problems that short trips to outer space or even the Moon do not have. One of the most important issues for any kind of space travel is fuel. Every space ship needs fuel to function, and the farther a spaceship has to travel, the more fuel it needs. The more fuel it needs, the heavier it will get.

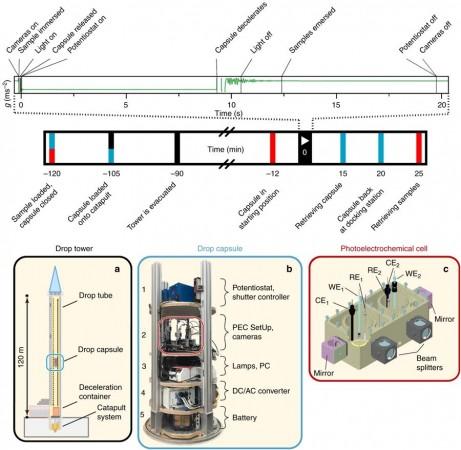

A multinational team of researchers decided to test certain emerging technologies and put their experiments to the test in microgravity by building a tall tower and dropping it in a theme park styled laboratory, notes a report by Gizmodo on the paper. "This is something new that hasn't been done before that was surprisingly successful," Katharina Brinkert, of CalTech.

Researchers reportedly placed their experiment—a 1.34 metre pneumatic tube within which a capsule is fired at a speed of 168 kph upward about 120 meters. It was conducted at the Center of Applied Space Technology and Microgravity (ZARM) in Germany.

Once fired, the tube falls for 9.3 seconds and inside it is the experiment, a light and electricity powered instrument that pulls protons out of water, then add electrons that in turn become hydrogen atoms, said researchers.

Hydrogen is an important fuel for spaceflight missions, notes the report, but synthesising usable hydrogen fuel in space has its own set of difficulties. In microgravity, or conditions that are incorrectly considered to be "zero gravity", there is a noticeable lack of buoyancy on liquids, so hydrogen bubbles that form as a result of the chemical reactions simply stay as froth in and stay locked in, this in turn stops atoms and ions from moving, notes the report.

To combat this effect, researchers built microscopic tower-like structures within the cell which guided and released said bubbles- in this case- hydrogen. Using this system, scientists were only able to harvest hydrogen, not oxygen at this time.

The study was first published as a paper titled, "Efficient solar hydrogen generation in microgravity environment" in the journal Nature Communications.

!['It's not Mumbai traffic, it's air traffic': Suriya apologises to Mumbai media after paparazzi yelled At Him for making them wait for hours [Watch]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806234/its-not-mumbai-traffic-its-air-traffic-suriya-apologises-mumbai-media-after-paparazzi.jpg?w=220&h=138)

![Bigg Boss 16-fame Sreejita De and Michael Blohm-Pape exchange wedding vows in dreamy Bengali ceremony [Inside Pics]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806233/bigg-boss-16-fame-sreejita-de-michael-blohm-pape-exchange-wedding-vows-dreamy-bengali-ceremony.jpg?w=220&h=138)