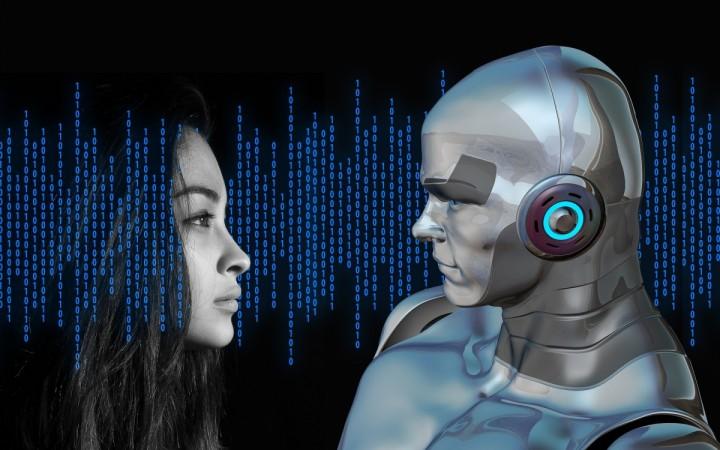

Ego seems to take prominence over intelligence when it comes to human beings seeking help from virtual assistants, especially from those that closely resemble human beings.

Research says, online learning platforms may actually discourage some people from seeking help on tasks that are supposed to measure achievement, making them feel dumb.

The study demonstrates that people are more inclined to see computerized systems as social beings with only a couple of social cues. Moreover, this social dynamics can make the systems less intimidating and more user-friendly.

Researchers found that participants who saw intelligence as fixed were less likely to seek help from an online assistant even at the risk of lower performance.

Daeun Park of Chungbuk National University in South Korea, who conducted the study, said, "We demonstrate that anthropomorphic (having human characteristics) features may not prove beneficial in online learning settings, especially among individuals who believe their abilities are fixed and worry about presenting themselves as incompetent to others."

Park and co-authors Sara Kim and Ke Zhang have done two experiments to reach this conclusion. In an online study, the researchers had 187 participants complete a task that will measure the intelligence of the participants.

So, on a difficult question, participants will automatically receive a hint from an onscreen icon – some participants got a computer "helper" which looked like human with features including a face and speech bubble. While on the other side, some saw the helper that looked like a regular computer, an icon of a computer.

In the first experiment, participants reported a greater embarrassment when seeking help from the helper icon with human-like features. It created more concern level about the self-image of the participants. In the second experiment, 171 university students accomplished the same task, but this time, they felt free to click the regular computer helper icon to receive hint without any embarrassment.

The researchers concluded that students, who were led to think about intelligence as fixed, were less likely to use the hints when the helper had human-like features than when it didn't. Moreover, the students chose to give incorrect answers rather than taking help from the human-like helper.

!['Had denied Housefull franchise as they wanted me to wear a bikini': Tia Bajpai on turning down bold scripts [Exclusive]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806605/had-denied-housefull-franchise-they-wanted-me-wear-bikini-tia-bajpai-turning-down-bold.png?w=220&h=138)