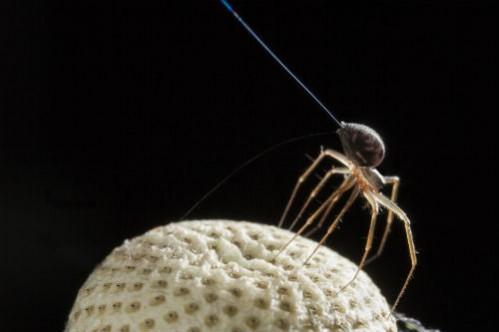

Spiders can distinguish living from non-living objects in their peripheral vision using the same cues used by humans and other vertebrate animals, according to a study published in the open-access journal PLOS Biologyby Massimo De Agrò of Harvard University in the United States.

The ability to detect other living creatures in your surroundings is a key skill for any animal - it is crucial for finding mates, avoiding predators, and catching prey. The movements of vertebrates and invertebrates are distinct from inanimate objects because their rigid, jointed bones and exoskeletons constrain the relative positioning of certain body parts. Most vertebrates can recognize this biological pattern of movement from very limited visual information, such as a point-light display, which shows dots representing the positions of the main joints.

Understanding spiders' behaviour

To investigate this phenomenon in invertebrates for the first time, researchers partially restrained 60 wild-caught jumping spiders (Menemerus semilimbatus) on a spherical treadmill and used a computer screen to show point-light displays on each side of their peripheral vision (only visible to their lateral eyes). They found that spiders were more likely to try to turn and face displays that showed random movements, compared to those that moved in a more biological way, with the distances between joints constrained.

The result seems contrary to the expectation that spiders should focus their attention on objects in their surroundings that appear to be living - potential prey, mate or predator. However, the authors suggest that this behavior may allow the spiders to focus their forward-facing primary eyes on unidentifiable objects to get a better look.

Complex vision evolved independently in vertebrates and arthropods and so the ability to distinguish living from non-living motion using the relative positioning of the joints has most likely arisen convergently in the two groups of animals.

"Jumping spiders' secondary eyes confirm themselves to be a marvelous tool," the researchers add. "In this experiment, we observed how they alone can tell apart living from non-living organisms, using the semi-rigid pattern of motion that characterize the formers and without the aid of any shape cue. Finding the presence of this skill, previously known only in vertebrates, opens up new and exciting perspectives on the evolution of visual perception. My co-authors and I can't wait to see what other visual cues can be perceived and understood by these tiny creatures."