India's adoption of the lithium principle has displayed a laggardness pervasive across individuals and institutions by the very nature of its deficit. Spurred by the Paris Agreement goals of clean energy conversion in automobile usage, Volkswagen, the world's biggest carmaker, said last year that it would begin a product blitz in 2020. Jaguar Land Rover has promised the same.

Volkswagen's fellow traveller Daimler set an ambitious target for electric vehicles or EVs earlier this year. This is not the first time in history when Volkswagen and Daimler have been involved in any sort of "blitz". Neither have Indian carmakers lagged behind with their pledges to go into EV overdrive.

Mahindra & Mahindra (M&M), which took over EV pioneer Reva a few years ago, taught the market about the mechanics of EV adoption and the stylistic expectations of a gear-obsessed, petrol-driven Indian consumer. As M&M found out, tastes which could not be dislodged were meant to be modified. Overseas OEMs with assembly plants in India like Volkswagen, Hyundai, Honda, Daimler, Mitsubishi, Fiat, Piaggio, and lately, South Korea's Kia Motors, have been slow on the uptake. EV production targets are unclear, but intermittent noises about new launches have been made in right earnest.

The Indian section of the industry responded in double-quick time when it came to getting the vitals embedded in Road Transport Minister Nitin Gadkari's exhortations to switch over entirely to "clean technology" (read EVs) totally by 2030 or get bulldozed. Promises by Maruti Suzuki and Jaguar Land Rover have not cleared the clouds, but shown the determined face of an industry almost fully reliant on sales of conventional fuel-driven vehicles.

The real alternative?

It was clear that electric cars were no more meant to be queer add-ons to the mammoth car market running on perishable sources of energy. They were the total alternative. Nobody can quarrel with the idea of replacing pollution-heavy, petrol-fuelled cars and commercial vehicles with cleaner and environmentally sustainable technologies. But when push comes to shove, threats from Gadkari may not help.

The auto industry, which has spent thousands of crores to raise capacities, has soldiered a rough road towards complying with the stricter BS6 emission norms set to kick in from 2020. The frenzied push for EV adoption compounds their troubles.

Whether the Modi government likes it or not, current battery capacities, sky-high car prices and dearth of supporting infrastructure may not encourage a lightning shift to electric.

Gadkari's fait accompli was in true Modi government tradition the typical diktat -- cavalier in spirit, high on quixotism, a brisk gloss-over of ground realities and pretty sloppy on outcome analytics. The government bulldozer is expected to be fuelled by hefty penalties imposed with impunity on the industry if compliance is not forthcoming. For Gadkari, the Paris Agreement on climate change and the promises of clean energy acceleration by India could not be ignored at any cost. Even if that cost was about suspending all logic (and logistics) in favour of ministerial grandstanding, though hopefully, on a temporary basis.

The lofty target for 2030 would amount to more than 10 per cent of the world production of electric vehicles (EVs) as endorsed in the Paris climate talks. Countries with high rates of electric car dependence seem better placed to make it happen.

That said, most Indian and India-based OEMs have for good reason made no clear announcements on targets for increasing electric car stock. The new launches are being readied, but that does not say much about their target markets. Or, target sales numbers.

News reports say that Audi India is readying the launch of its electric car by 2020, while Hyundai has shelved plans to launch a hybrid and is now shifting focus to an electric car. On September 6, Nissan revealed the all-new Leaf – which will travel nearly 400 km between charges --, and while the brand has confirmed that it will test the car in India, it now has the incentive to launch the Leaf in India as well – over 6 years after it was first launched in the US market.

Tesla and Nissan's electric cars are yet to reach Indian auto showrooms, even as consumers fence-sit the possibility of seeing new cars which squeeze more juice out of less charging time.

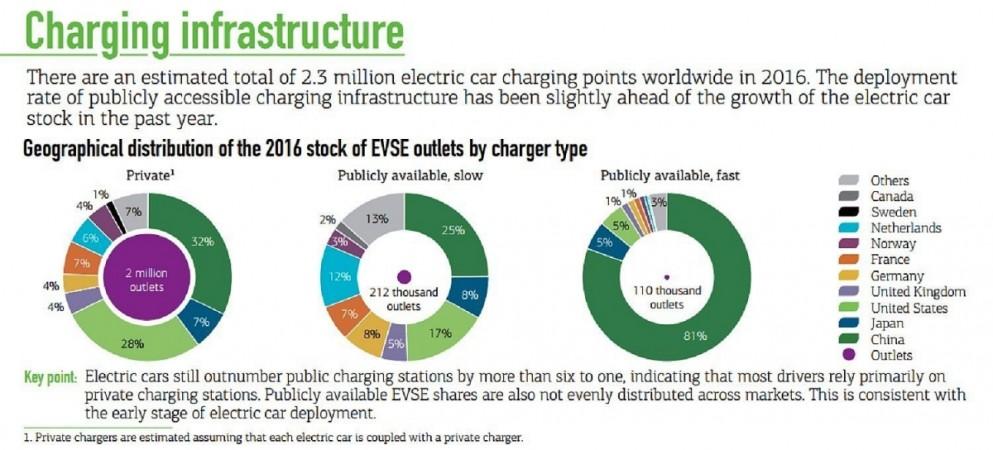

The services side of things reflects buyer apathy as much as it does governmental lack of vision. India's tentative stock of low chargers for battery electric cars, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and other EV categories was a measly 328 units in 2016, a year which witnessed just about 450 new EV registrations. The picture for fast chargers is even more dismal; just 25 units up and running in the public space during 2016. India's rabid bone of comparison China is looking to have 800,000 chargers up and running by the year-end.

While the possibilities are exciting despite a virtually non-existent infrastructure, the fact that the EV market is not poised for a giant leap is primarily attributable to high prices, maintenance costs and consumer worries about availability and speed of charging.

Scroll down for video

Yes, the possibilities are exciting enough. Thanks to a highly incentivised solar industry, India is poised to gain greater access than ever before to thin film solar PV cells. These can be integrated into car roofs. Transparent ones that utilise invisible spectrum rays can be integrated in windshields and window glasses. By expert reckoning, 300-500W could easily be generated while the car is running in day time or parked in the sun. This would raise the range, if only a bit. Every little improvement counts.

Rhetoric versus real targets

Niti Aayog's recommendations to get the electric bandwagon rolling do not appear workable. The central planning body aims to get electric vehicles to 44 percent (10-15 million) of the fleet by 2030, and is aggressively favouring them with tax rates 31 percentage points below those on hybrids and internal combustion engine cars under its new harmonised GST sales tax.

The target of 10-15 million electric cars on the road by 2030 would require the construction of roughly five battery manufacturing facilities with the production capacity of the completed Tesla Gigafactory – 150 Gwh/year (gigawatt hours per year).

Tesla's Gigafactory 1's projected capacity for 2018 is 50 GwH/yr, and its date of final completion is still a matter of speculation. The 150 Gwh/year capacity, whenever that is achieved, would enable Tesla to produce 1.5 million cars per year.

Currently, across categories, India sells only 22,000 electric vehicles a year. Set off at a mid-point target range of 6-7 million cars zooming around on India's potholed roads in 2030 would require the combined production capacities of roughly five Tesla Gigafactories.

Going by the Indian auto industry's production estimate for electric cars, the 2030 target would require eight to ten times the global stock of such vehicles. India would need to sell 10-15 million electric cars in 2030, in comparison with just about 5,000 electric cars the country had on the road in 2016. Or, compared with a mere 1.3 million on the road worldwide in 2015.

Stiff headwinds face the fledgling EV industry, despite the REVA, India's first EV rolling out over 16 years ago and taking the UK market by storm. Yet, spurred by Gadkari's faith in battery power, the boardrooms of Maruti Suzuki and Tata Motors are abuzz with market reconnaissance debates prior to testing the placid waters for a whiff of EV flavour.

Scroll down for video

Right now, the flavours inspire us not. Mahindra Electric's e2oPlus and the eVerito are just about the only electric car options available on the market. Tata's electric Nano is undergoing early tests in Coimbatore, while Maruti Suzuki has a fourth assembly line being readied in Gujarat – ostensibly, to incubate an upcoming electric car. Tata's Tiago EV concept has been revealed in the UK. The Tiago and Nano's electricals could provoke a degree of curiosity in a dull EV market, though a 2018 launch seems unlikely.

EVs, in particular electric cars, are not yet on pace to become more mainstream in the future. Even a marked acceleration in the pace of their adoption may not really mean that India will not be stuck with more internal combustion engine vehicles running on petroleum-based fuels than we want. This is due to the fact that cars stay on the road a long time and the vast majority of cars sold today and for the next few years are of that variety, and the number of cars on the road is only going to swell due to the proliferation of vehicles in the country.

Alternatives, and shifting goalposts

India saw production of nearly 2.5 crore vehicles in 2016-17, comprising motorcycles, scooters, cars, SUVs, three-wheelers and commercial vehicles. The challenge is to shift this fuel-guzzling multitude entirely to electric in roughly 13 years. The government's orders to car makers are to not only make electric cars, but also port the battery-packs onto buses, three and two-wheelers.

The questions which will follow as a natural corollary to widespread adoption of battery cars are already being raised. Anybody in cities like New Delhi, Mumbai or Bengaluru knows that residents can park only on the streets. If these are EVs, how do they get charged? How many locations will have electric outlets, including off-street? For that matter, how ready are our proposed Smart Cities when it comes to provisioning for charging stations?

And, whenever EVs go truly mainstream, would they hypothetically be a disincentive to the public from using public transport or carpooling, even as they create a new breed of battery-powered traffic jams? These are questions to thrash out well before the future catches up with India's stressed out infrastructure and snail-like pace of civic project completion.

Economy of scale for the EV industry may not be feasible right now when scale does not truly exist and cost differentials are staying high. Struck by the insane costs of lithium battery-pack development, car prices continue to be inversely proportional to battery energy density -- the EV version of mileage.

A lithium ion battery alone constitutes 30-40 percent of a car's selling price. Battery-driven buses and trucks are in the unaffordable range and considered rather unviable for long-distance travel. Tata Motors retails its pure electric bus 'Starbus Electric 9m' and hybrid 'StarBus Electric 12m' launched in January 2017 at indicative pricepoints of Rs 1.6 crore and Rs 2 crore.

India would still go full speed ahead toward EV adoption as Gadkari and the BJP government insist in good faith, but government and industry should be investing in other alternative vehicles and fuels as well.

Instead of GST tax breaks, the government can achieve much more by incentivising alternative fuel technologies and disincentivising those based on fossil fuels, not to mention coming out with a well designed package of economic incentives for the industry to enable a paradigm shift. A tax break of 12 percent for electric vehicles, for example, makes sense, but not when lithium batteries attract 28 per cent GST when sold separately to consumers choosing between different battery brands at a point of sale.

Resorting to frequent policy changes will confound the auto industry and undermine its well cultivated market turf. In July this year, the government had actually told Parliament that there was no plan to make a switch to 100 per cent electric vehicles by 2030.

For now, auto OEMs will need some quick and dirty launches in place by 2018-19 as they brave short-term pain in search of long-term gain. In the interim, the government must delete the bulldozer word out of its rough draft for clean energy.

![India Auto Roundup: Maruti Suzuki, Mahindra have exciting launches in November [details here]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/805520/india-auto-roundup-maruti-suzuki-mahindra-have-exciting-launches-november-details-here.jpg?w=220&h=135)