In the 1990s, the business mantra for India Inc., so to speak, was "diversification", followed by "core competence."

While the former was synonymous with forays into unknown territory, the latter was a classic case of belated wisdom dawning upon over-enthusiastic industrialists who realised that random diversification wouldn't pay off.

It's a different matter that lenders, suppliers and employees would often become collateral damage in the process. The aviation foray — Kingfisher Airlines — by the UB Group is a classic example, though it happened after the 1990s.

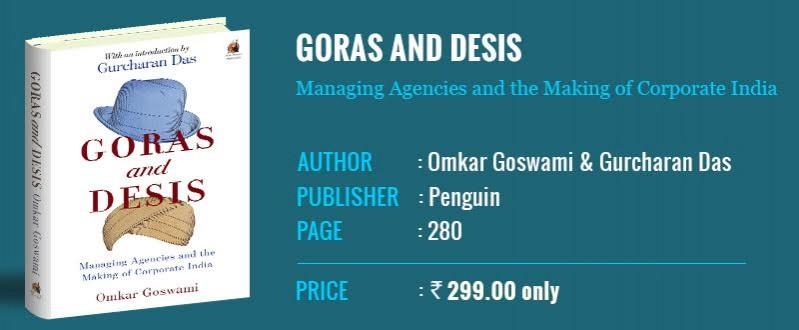

But if one were to look into the history of business in India, these tendencies existed even before Independence when the concept of managing agency existed, assisted in part by Ponzi scheme. Economist Omkar Goswami's book Goras and Desis (Penguin, Rs 299) is a gripping account of how managing agencies originated in India, their heyday, and slow death by 1970.

At a basic level, the concept can be compared to a small partner in a political coalition calling the shots while the dominant party plays second fiddle.

Managing agencies started as a form of business organisation that gave entrepreneurs an opportunity to start new businesses with little capital but hold dominant control over cash flows.

While the first chapter of the book explains how they came into being, the second and third give interesting glimpses into how the managing agencies squandered away the gains and gradually came to be perceived as a bunch of dishonest people out to make money through shady deals.

The first managing agency was started by Carr, Tagore & Company (CTC), way back in 1834. While William Carr was a British indigo merchant, his more enterprising and ambitious partner, Dwarkanath Tagore, hailed from a prosperous zamindar family. If you are wondering if he was Rabindranath Tagore's grandfather, you are right.

CTC began with commodity trade, exporting indigo, silk, sugar, saltpetre, hides, and rice. Tagore, who was canny, was not content with just trade, given his business acumen and ambitions.

Soon, a string of new businesses started, from coal mines (Ranigang, in Burdwan) to logistics (steamboat service under a venture called Calcutta Steam Tug Association). The management of the service was with CTC.

The Association was profitable in its initial years and rewarded capital investors. The amount invested, the profits and the dividends to shareholders had all the hallmarks of a successful business, according to Goswami, a holder of Master's degree in Economics from the Delhi School of Economics and D. Phil (Ph.D) from Oxford.

He then went on to teach at the Delhi School of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University and the Indian Statistical Institute, and served on the boards of many listed companies, including Infosys.

Goswami gives sufficient details at most places in the book. "The Calcutta Steam Tug Association had sufficient capital. Starting with Rs 200,000 in 1836, it soon doubled its equity base to Rs 400,000 in 1838, and then to Rs 500,000 in 1842... After paying Carr, Tagore & Company its annual 5 percent on net profit, the Association earned enough to declare twice a year. During 1836-44, total dividends per share announced by the Association amounted to Rs 1,390," he writes.

But some years later, the Association faced its Satyam moment. "In 1848, two years after Dwarkanath's death, it was found that thanks to some lax accounting the value of the Association's assets was Rs 300,000 and not Rs 754,000, as reported to the shareholders by the Association," writes Goswami.

But the first setback did not deter Dwarkanath, who set his eyes on another venture — salt pans. It was a business that was doomed from the beginning and had to be wound up in 1849. Goswami does not say when the ill-fated Bengal Salt Company was formed.

Concurrently, CTC also floated another venture, the Steam Ferry Bridge Company, to ferry passengers between Howrah and Calcutta. The company's Rs 2 lakh equity issue was oversubscribed by the uber-rich of Calcutta, convinced as they were of the business prospects of the ferry service. But the project was bogged down with problems ab initio, leading to its liquidation in August 1842. Again, we wish Goswami had given the date when the company commenced business or date of formation.

There was yet another foray by CTC, this time into the lucrative tea cultivation and export. The final tally, writes Goswami, read as two successes (coal and steam tugs) in addition to tea, while there were three failures — salt, Steam Ferry Bridge and banking.

The need for a bank that would assist in funding many ventures paved the way for the Union Bank of India in 1829, with help from Mackintosh & Company. But Dwarkanath and his partners forgot a cardinal principle of banking, spread risks to avoid going bust. Its disproportionate exposure to the indigo trade dominated by irresponsible planters ended up in huge bad loans from which it could not recover completely, forcing its ultimate closure on December 31, 1847.

In its heyday, CTC was apparently an employer of choice, to borrow a modern-day phrase. Goswami, who runs a consultancy firm called CERG Advisory, provides insights that would make many an employee of these days feel envious of his 19th century counterparts, when put in perspective.

"In their first four-year contract, junior assistants typically started with Rs 400 per month, this would rise to Rs 550 a month in the fourth year plus an annual bonus of around 25 percent... At the end of each contract, the employee received a fully-paid-for return passage to Britain plus a holiday of three to six months at 50 percent to 70 percent of the pay. Senior assistants, typically with a decade of experience to show, would get a salary starting at around Rs 2,000 per month and rising to a princely sum of Rs 3,500 plus bonuses."

The second phase of managing agencies — 1875 to 1947, according to the author — saw the emergence of the British (goras) who dominated the managing agency system and the gradual rise of Indians (desis). But unscrupulous elements within the Indian ranks just could not resist the need to make a fast buck, questioning the need for this existence by Indian freedom fighters who had become suspicious of these greedy men (Goswami calls them "uncouth parvenu"). The trend gained momentum during the post-Independence era.

One such element was Haridas Mundhra, who earned his riches in wartime profits. His eagerness to use his money for an acquisition spree had a major temptation that many such people find hard to resist: rigging share prices in stock markets. The purpose was simple: to use shares with inflated prices as collateral to secure more loans from banks to fund even more acquisitions. When the share prices fell, everybody was at a loss. To add to his woes, Mundhra's rivals sounded out the RBI and the North Block. Besides rigging share prices, Mundhra also pledged two sets of share certificates to banks and both were found out to be fake, as revealed subsequently during a probe.

Mundhra not only had banks on his side, but also managed to drag the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC). In 1957, the savvy punter-trader had managed to convince the then finance minister T T Krishnamachari that led to the state-run insurer buying shares at high prices of firms owned by Mundhra. It proved to be his undoing, as the issue snowballed into a scandal when none other than Feroze Gandhi raised the issue in Parliament. A probe found Mundhra guilty and he faced the same fate as Satyam's Ramalinga Raju. The controversy also saw the exit of the minister.

The Mundhra episode, along with increased dislike for managing agents and a decisive shift towards stricter controls over the economy, saw the legal demise of the managing agency system on April 3, 1970, after a chequered 140 years.

Goras and Desis highly-is recommended for those who prefer to read the history of businesses worldwide since it also delves into the evolution of conglomerates in Japan, South Korea and other countries. Students of law and economics will also find the book interesting as it details how the Nehruvian system of controls that stymied the growth of entrepreneurship during the initial post-Independence years.

The book provides glimpses of how traditional business families rubbed shoulders with politicians the wrong way, even if the dislike for socialism is overwhelming.

The author could have delved more into specifics pertaining to the initial days of Dwarkanath Tagore's managing agency's exploits, not to talk of a typo with regard to Union Bank of India (the year of commencement is 1829 and not 1929 as mentioned on some pages).