Making a fortune by helping people dig up whatever information they seek comes with its share of fortunes. And, pitfalls.

Regulators hound winners of the game on every conceivable reason, marginalised rivals break into unmitigated slander, arcane rules and regulations are reincarnated or redrawn to highlight every omission and commission, or elaborate baiting games begin inside solicitor firms eager to cash in on penal action. That's the way it should be: though oftentimes, the wheels of justice grind slowly, but surely in favour of the defendant. Sadly, a record fine of $2.7 billion levied late last month by the European Union (EU) on search engine giant Google doesn't look like an exception to the rule.

A path-breaking company which has spared no pains to cover its bases in the SMAC space (social media, analytics and cloud), and broken new ground in sunrise domains like largescale data mining, artificial intelligence and automotive electronics deserves more than a passing look. Google's shareholders have paid close attention and preferred to stay invested, while the company's rock-bottom attrition rates – at close to zero -- match the best in the business.

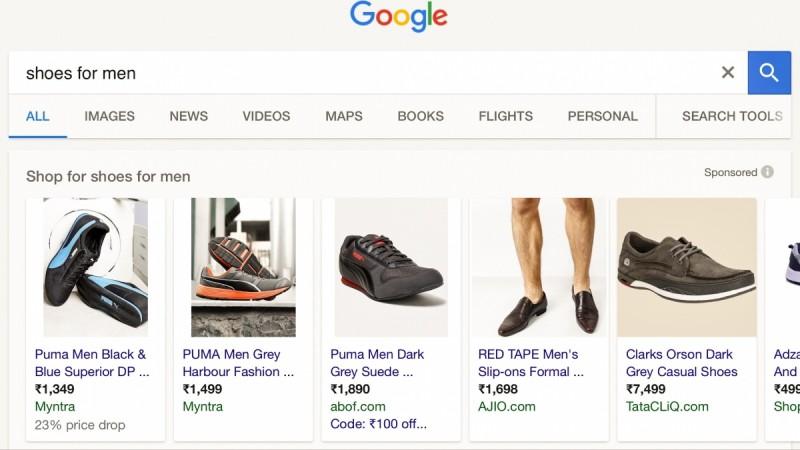

EU anti-trust officials fined the search giant for what it claimed was unfairly favouring some of its own services in ads thrown up by its search results, over that of its rivals. The fine will not be a scratch on Google's offshore cash pile of $42.9 billion or its European revenues of over 22 billion Euros, which could have provoked a regulatory move of this kind, but did the regulators really have a case to make?

For, EU Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager's charge that Google's abuse of its monopoly in online search to push its own services via ad placements inside search results, would apply to any market where a company with a bulk of the consumer mindshare is allowed to push select services and products with immunity. Think Carlos Slim Helu and Telmex.

The old normal

According to the commission, Google's price comparison service Google Shopping (earlier, Froogle) had systematically favoured Google's own comparison-shopping results by giving them prominent placement at the top of its generic search results and demoting links for rival offerings to pages further down, where users hardly venture. Denying business to rivals by shielding customers from their offerings deserved exemplary punishment, said Vestager, and her EU compatriots nodded in unison.

Almost every retail major, from Walmart and Carrefour to India's Bharti Airtel and Reliance, have pushed select operator and partner products and services through advertisements and leaflets, not to mention their own business divisions, within the ambits of their retail spaces and earned hefty commissions for their pains. Banks hawking third party insurance products and bundling mutual funds, Systematic Investment Plans, gold bonds, housing loans and life insurance products with savings and fixed deposit accounts is not new. Systematically promoting ignorance among customers about the products and services offered by rival businesses through either denial of access or withholding information is part and parcel of every company's growth plan. That's the way competition works.

Stalwart corporations operating in the retailing, automotive and banking sectors in developed markets, have for over 75 years, been quick on their feet to exploit longstanding relationships with customers to shore up operating margins.

Squeezing more juice out of a captive market is part and parcel of being leader in a particular business space. But when the company essentially becomes the market as in Google's case, the right questions need to be asked, which the EU is doing. However, EU's preference for on-the-fly penalties backed by assumptive lines of reasoning, -- assuming Google is indeed a credible threat to every online/offline business around -- defies an easy answer.

Googling isn't prescriptive, profit is

Google's record fine and the alleged offences look minor compared to what put Microsoft in the legal hot seat – bundling the Windows operating system with its Web browser, while intending the browser to double up as a future advertising and paid apps development tool. Or, Apple being asked to repay $14.5 billion in back taxes in Ireland.

With Google, the intended or unintentional act of pushing rival business adverts and links below customer eye level does not amount to deliberately concealing information, but makes it provisionally more cumbersome for the customer to see it – unless he harbours a specific intent to search out an ad showcasing a particular offering from a Google rival or non-partner.

Yet, the act of making rival business results "invisible" (but still findable at the bottom of the search result pages if one cares to look hard enough) need not be construed as deliberate concealment of information by Google, but an act of unconscious denial of its existence by the customer due to his ignorance of such a product or service. Or, simply, his lack of interest in a particular product which Google believes it has no part in influencing.

The company does not claim that it makes moral or ethical judgements (nee choices) on behalf of its users. By that token, the customer cannot either, unless he wants to – in short, he must search within the results by design to find out more about a rival product which Google says it has not deliberately hidden from him.

That apart, the business of ad sponsors paying Google for top-of-the-screen visibility is kosher among the European search engines as well, and EU anti-trust regulators should not be having a problem with Google doing the same simply because it leads the search market.

Google's argument rests on the fact that it hasn't coerced the customer overtly through its seemingly subversive way of presenting seller results on Google Shopping. And, by no leap of logic, do its methods of presenting information rank among the worst marketing practices of the corporate hemisphere.

The spray-and-pray approach to enticing people to buy from your partners is as old as marketing, and when applied to a search engine giant, asking the right questions was to be expected of the EU anti-trust. But there will be no single answer which pleases EU, or for that matter, every person across socio-cultural and ethical categories. The unusually hefty fine on Google was best not levied.

The Alphabet trap

Google's comparison with another trendsetting firm like Apple would be rather incongruous, though necessary: both never rested on their bread-and-butter businesses, instead pushing dollars into R&D ventures which staggered the imagination of shareholders, while keeping them excited, hopeful and fearful of the future. The pressing question was whether piecemeal acquisitions -- which were not much in sync with what shareholders believed was the directions these companies should take --, really the right way forward?

Before October 2015, Google's gigantic advertising revenues had cast a comfortable shade in which ambitious, zero-revenue projects like DeepMind or upcoming startups like Waze could shelter. As it gained a special interest in acquiring startups breaking new ground in navigation and mapping, deep learning, neural networks, computer vision, natural language processing and robotics, Google conjured up a corporate superstructure called Alphabet, while focussing more on AI-based applications around software, instead of its earlier focus on AI hardware. The idea was to build AI tools to fix "old problems", as Halli Labs, a four-year-old Bangalore-based AI startup acquired by Google this week, would later explain.

The ascent of Google's holding company Alphabet meant that Google's other enterprises, including search and the controversial advertising business, went off its balance sheet, putting them under stronger regulatory scrutiny. The marquee search engine business, where multiple advertising and branding stratagem converge, is bearing the brunt of legal suits on both sides of the Atlantic.

Alphabet corporation spent $1.3 billion on acquisitions during the first half of 2013, with $966 million going to Waze alone. These will be the noetics propelling Google into its next phase of growth and market creation. Whether the company can afford to get trapped in legal brawls, either by default or of its own making, is a question to ponder. How such cases finally turn out could fundamentally alter the way Google – and other tech giants – do business. They might also validate a critical viewpoint: that European authorities are laying down new markers for more hands-on control of how the digital world operates.