Insolvency is more than the flavour of the season when there are no more favours to be done. A National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) inquiry on steel company loan paybacks is being carried out on the recommendation of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The deliberations have proved to be stinging verdicts on the profitability of companies seconded for insolvency by RBI under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), following several failed attempts at loan recovery.

Equally chastening has been the sense of resignation, -- more in the nature of a barely disguised sang froid --, among companies towards their prescribed fates to be assigned by NCLT. Not much of an objection to insolvency proceedings at all, as things stand.

Steel is a cyclical industry and firms battling debt is not new. But successive investment cycles, as a byproduct of booming stock markets and optimistic investors, could make it tempting to relax one's grip at the wrong moments. As the bosses of 12 steel companies are finding out, complacency is not an option in basic materials industries, and the wrong results lead to acute pain.

Auto grade steel manufacturing giant Bhushan Steel is facing the heat on behalf of its struggling power venture Bhushan Power & Steel as well. The two companies together owe 41 banks, including seven foreign banks, more than Rs 80,000 crore. Privately held Bhushan Steel, which is said to owe banks a whopping Rs 44,447 crore, has all but run out of steam after some mild brawling to prove SBI wrong (the company had alleged that the bank inflated its dues by around Rs 100 crore).

NCLT death row

Last week, Bhushan Power, promoted by the Singal family, had not objected to the insolvency proceedings but requested the court to ensure the company was treated as a 'going concern'. Data from Capitaline reveals that the company reported net loss of Rs 2,433 crore in 2015-16 on the back of Rs 8,491 crore in revenues. The firm reported net loss of Rs 3,501 crore in 2016-17 on revenues of Rs 15,027 crore. Its annual report for 2015-16 says that it has been facing severe stress in its debt servicing over the past few years.

Other companies on NCLT's death row include Jyoti Structures, Monnet Ispat, Alok Industries, Amtek Auto, Era Infra and Electrosteel Steels. Among them, the case of Electrosteel Steels stands out like a sore thumb.

Electrosteel is among the six companies which were specifically referred to the NCLT for a debt resolution plan.

Kolkata-headquartered Electrosteel is not among the top five loan defaulters on NCLT's tickoff roster, owing Rs 14,000 crore in all and Rs 1,404 crore to SBI alone. An unduly high share of non-banking debt is what sets it apart from the rest. Electrosteel is not known to have repaid debt since April 2015. And, it is understood to owe lenders Rs 9,600 crore and a "couple of hundred crore more to non-financial creditors", as pointed out by a company source in various news reports.

Fresh loans have not helped the company turn the corner. Even as SBI moved in to recover dues by taking control of its assets and manage it under the IBC, Electrosteel did not demur.

This was a clear triumph of experience over hope. For, Electrosteel had debt of Rs 10,274 crore on its books in fiscal 2016 and lenders had first opted for the strategic debt restructuring (SDR) path to resolve the issue.

The SDR was introduced by the RBI to tackle the issue of burgeoning debt by allowing banks to acquire control of a defaulting company by converting loans into equity. Following this, the banks were supposed to bring in new promoters and upgrade their sticky assets to standard ones. Electrosteel was the first case where lenders invoked the SDR mechanism, as reported in financial daily HT Mint.

The Electrosteel Steels management would quickly blame the failed debt restructuring plan in September 2013 and a botched line of credit for the company's woes.

Riding the market wave

In many ways, Electrosteel was a product of unreal market euphoria which did not measure companies on fundamentals like earnings potential, asset quality, or even revenue history – often, like it repeats history today. When Electrosteel floated its initial public offering (IPO) in late 2010, investors did not ask too many questions. The company hadn't finished a full year of operations and had no earnings or revenue history. In fact, one of the main purposes of its IPO was to finance its maiden manufacturing plant, for which private equity players would have been a better bet.

In the event, the IPO did not have a promising start, and Electrosteel and its IPO managers ran foul of the market regulator after SEBI received complaints about non-disclosure of a rejection of the company's proposal for forest clearance at the Kodolibad iron ore mine. Electrosteel and its merchant bankers SBI Cap, Axis Capital and Edelweiss Financial were hit with fines totalling Rs 2.5 crore on that occasion.

The company had serious execution issues, and it was all downhill after that, as it teetered on the edge of bankruptcy in a couple of years. After the IPO price of Rs 10-11 per share, it went as low as Rs 2 per share. It traded on July 27 at Rs 4.73 per share, down 8.33 percent over its previous closing. Essentially, the company stock is trading at over 50 percent below its IPO price nearly seven years later.

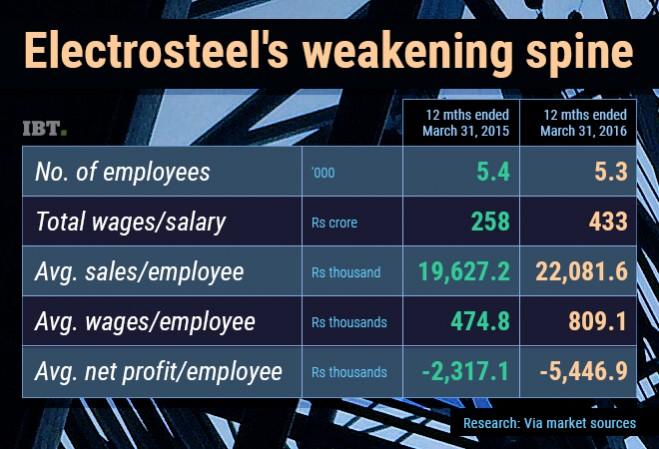

When management promises to investors turn out to be a sheer mirage in a sea of IPOs, instances like that of Electrosteel Steels are glaring examples of the quantum of mismanagement (see chart above) which Indian banks and taxpayers face. Not to mention greed and misuse of power in the top echelons of banking which is the root cause of humongous NPAs running into the lakhs of crores encumbering India's PSU banks.

Besides declaring insolvency, the possibility of calling international bidders for the steel assets after they are put on sale would work -- provided it does not set a precedent. It is equally vital for banks to take care while appraising loan proposals in future and exercising stronger oversight over disbursements to ensure that loan money assets are created and loans not diverted. This will help projects generate sufficient income to repay their loans on time.

The RBI expects the average GNPA ratio of banks to increase from 9.6 per cent in March 2017 to 10.2 percent by March 2018, and fears that this number could easily rise. Banks have reduced lending to the steel, infrastructure, construction, real estate, oil and gas and telecom sectors. These are the key drivers of the economy and also comprise the highest amount of stressed assets within the banking system.

Withholding lending to these sectors will not work for long. Derisking through the agency of discretion may be a safety valve for banks at the moment, but may not help the Indian economy even in the medium term.