On November 8 last year, only a hermit or a Finance Ministry official would claim ignorance of the ubiquity of cash and its dominant usage in India. The most bizarre alibi of all to justify the devaluation of selected currency denominations back in November was that it would work as a magic spell to realise a cashless society, and in a single stroke, eliminate most ills facing India as a society. All it takes is 50 days, Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised emotionally.

The denominations illegalised by the government amounted to Rs 15.5 lakh crore worth of total currency in circulation at the time demonetisation was sprung on India's unsuspecting citizens.

Most of them gamely cheered on the move as a quick-fix to eradicate black money; or increase direct tax compliance in a country where only 1 percent of the population -- 1.25 crore out of a total population of 123 crore -- paid up its income tax in 2012-13.

But the truth is: then and now, eliminating black money and increasing tax compliance was and always will be a byproduct of robust policy oversight, strong institutional independence and quality of citizenship.

Once the government confirmed its suspicions that black money has multiple levers to its creation and control, as played out in diverse sections of the economy, the private and unorganised sectors, stock and money markets, besides trade, and not a monolithic entity which could be hushed into silence through artificial currency shortages, it (the government) switched track to new rationales. As stated earlier, the most bizarre of the lot was the de facto creation of a cashless society.

Wishing on a vision

Cashless always signposts digital, went official logic. And, digital in every situation points to progress, said Niti Aayog, the government's rechristened version of the erstwhile Planning Commission. Modi's Finance Minister Arun Jaitley agreed. The data doesn't.

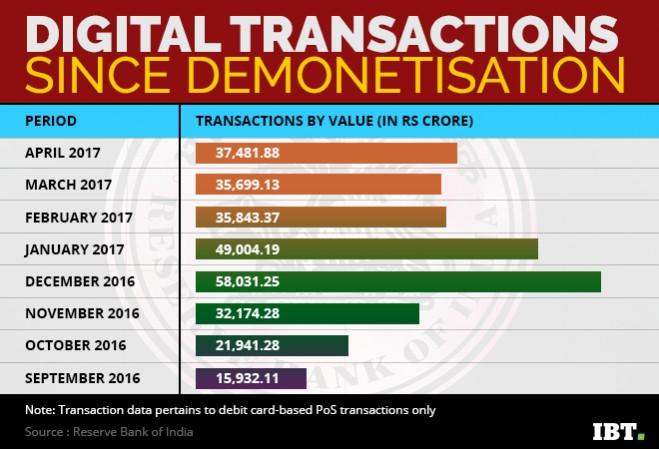

Digital transactions using debit cards rose 4.99 percent in April this year over March, but December 2016 is a memory. December was when, faced with the demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 100 notes in the previous month, and left with no recourse but seek digital intervention, the number of non-cash transactions witnessed a huge spike.

Modi's demonetisation stress led to digital transaction volumes peaking in December, but falling 18.42 percent in January, and a further 37 percent in February. Growth in digital usage has remained flat since.

The relentless pursuit of the cashless dream by creating a currency shortage as it did, would in Finance Ministry parlance, "encourage" almost 90 percent of India's population which uses cash to transact its way through life to move over to digital transaction modes – online, Point of Service (PoS), at the very least, ATMs. This was convoluted logic in action at best, and phantasmagorically middling thought process at worst.

The results were close to what the critics feared, and cheer leaders continued to ignore. In January, at the height of the demonetisation-fuelled currency shortage, the volume of digital transactions fell 18.42 percent from the highs of December. But this was minimal under the circumstances, considering that December transactions were at record figures thanks to the compulsive digital conversions of habitual cash users during the month. Coming from a wider base, the January fall in transaction numbers was not substantial enough to warrant dismissing Modi's digital dream as a myth.

A digital shift? Not really

Data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy indicates that new currency circulation actually showed an increase in the period of one week ending January 13, 2017, at 5.9 per cent, with the RBI's three currency mints going full blast on production. The government declared the match won before half-time. Digital is the new norm, it said. That appeared to be a self-goal, for digital transactions fell in February as well – this time, by 37 percent.

Does the temporary higher circulation of the new currency explain this fall? Probably not, for even though many semi-urban and rural ATMs were still being recalibrated for the new notes during the January-February 2017 period, and many as usual had no cash at all despite the higher availability of currency, it was clear that more people were emboldened to risk cash transactions -- simply because they were comfortable doing it, and often cost-effectively too. Traders and farmers who exchange their produce and services for cash, were justifiably relieved till the second week of March, when the currency supply tightened up again.

Finance Minister Jaitley reminded us that digital India was on a roll and higher supply of the new currency would negate the "inconvenience" caused by demonetisation. But he would again, knowingly or unknowingly, miss the wood for the trees. For, the very fact that urban ATMs were running out of cash revealed that demand for currency continued to be high, and the higher currency circulation was insufficient to meet it. But Jaitley insisted that digital transactions had become the new normal.

The bottomline was clearer by March when another currency supply crunch struck the common man, and digital transactions faltered further. The bottomline was that digital modes of settling transactions were far from being a way of life in urban or rural India. RBI data for April indicates that digital transactions dropped a cumulative 31 percent from their December peaks.

The preference for debit card transactions (see chart above) as a reliable indicator of measuring post-demonetisation spending, is driven by its high levels of usage by those in the sub-Rs 3.5 lakh per annum salary category, who form a majority of Indian salaried workers.

It is a fact that credit cards are pushed almost as much into digital usage as debit cards. However, credit cards are essentially non-collateralised debt, and as stochastic data, less accurate in revealing user behaviour or financial status when it comes to spending money on essentials. Real-time transaction spends using debit cards, on the other hand, are based on accounting for actuals, -- which more accurately reflect the financial situation of their user bases --, thereby serving as better indices in gauging the success of the digital medium as a realistic alternative to cash.

The very fact that digital transactions have stayed flat since January shows that inhabiting a digital reality will elude us for some time to come. That would be unfortunate, though not a national tragedy by any stretch of the imagination.