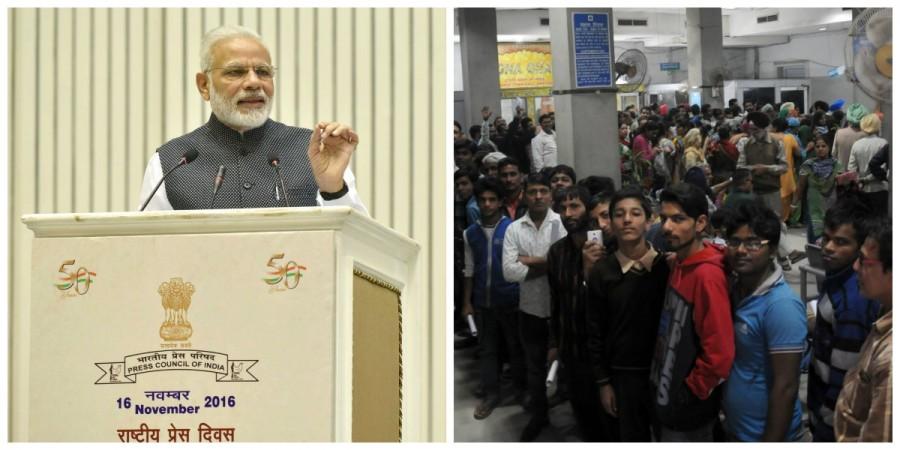

Prime Minister Narendra Modi's decision to scrap Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes in a surprise announcement on November 8 has not been completely endorsed or rejected by the people, but the Economist says it could turn out to be Modi's biggest political blunder yet.

"The surprise scrapping of what amounted to 86% of the cash in circulation could, in fact, turn out to be the worst mistake of Mr Modi's career," the London-based weekly wrote.

The dominance of cash-based transactions in many sectors of the economy and the lack of banking facilities in many parts of India makes Modi's move a wrong gambit, according to the magazine.

"For many among the estimated 80 percent of wage earners who are paid in cash, for the tens of thousands of villages with no banking facilities, and for the traders, drivers, farmers, prostitutes, beggars and others who work in the 'informal' economy that accounts for anywhere between 25 percent and 70 percent of India's GDP, it has brought anxiety and hardship," the weekly, which has rarely taken a favourable view of Modi and the BJP, wrote.

The Financial Times preferred to call it a significant move in Modi's avowed decision to crackdown on black money, starting with the tracking of large cash transactions, typically done at luxury and jewellery stores.

"The campaign hit its apogee last week, with New Delhi's surprise ban on the use of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes — a radical action intended to catch black money hoarders," the daily wrote.

Besides, the decision, which the BJP prefers to call a "surgical strike on black money," is ill-advised in an economy where cash transactions are prevalent in a big way, according to the Financial Times, besides raising doubts on the benefits of such a decision.

An analyst at JPMorgan told the daily that it's difficult to assess the impact on India's economy. "No country has done this kind of shock therapy. We don't have any precedents of doing anything of this sort. We are flying by the seat of our pants," Jahangir Aziz, global emerging markets analyst at JPMorgan, told the Financial Times.

It said that such unprecedented measures are undertaken only during exceptionally bad conditions "such as in Germany after the second world war, or the former Soviet Union — or in the throes of hyperinflation," and not by a country like India that is growing at upwards of 7 percent.