As China aims to cement its grip in the Eurasian and African regions through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing's traditional rivals like New Delhi and Tokyo can't look the other way. And soon after the Chinese unveiled their project, India and Japan came up with the idea of setting up another silk road, showing the Chinese their own alternative.

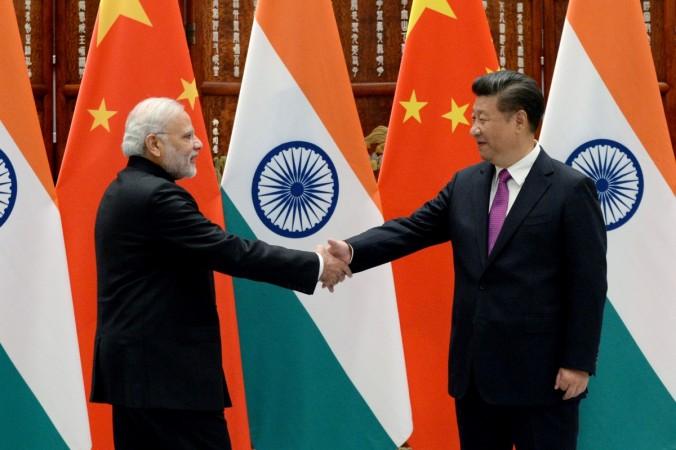

Just after the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, unveiled the BRI in May, Prime Minister Narendra Modi revealed a vision to counter China at a meeting of the African Development Bank in Gujarat. The idea was conceived during a meeting between Modi and his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe in November last year and it was named the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC). The AAGC initiative is an India-Japan partnership to integrate South, Southeast and East Asia with Oceania and Africa.

Now, the point is: The plans and counter-plans for nationalist projects that reach out to international goals of integration and development eventually make market and community as the language of foreign policy. Although on the face of it, the language that these competing nation-states are speaking is of power, the basic currency of international relations.

Why speak in language of power and not trade or community?

The problem with India's foreign policy makers is that they are still burdened by the baggage of the early and mid 20th century foreign policy calculations of the west. The conflict of power and interest of the colonial western nation-states had driven the world towards the great wars. In the post-World War II period, however, when Europe was left devastated, it was the language of market and community (and of course, collective security) which had taken over. The days of regional integration that followed replaced the language of war with the more peaceful one of a trading community.

Although we are seeing new signs of anti-European Union behaviour now, one can't deny the fact that the European integration had a profound impact on world peace after decades of clashes and bloodshed.

In our parts of the globe, we also need to jump one step -- the one of the national clashes -- and land in the phase of peaceful engagements. The Chinese, unlike the West, have followed a more prudent foreign policy based on trade and not supply of cash and arms, something the Americans have done over the years to destabilise regimes. The advantage of the Chinese strategy is that it helps both Beijing and the countries it help with trade and infrastructure.

The language of trade earns China more loyal friends and not inconsistent allies that the US had in various parts of the world at times. India is struggling to deal with the growing Chinese influence in its neighbourhood because of this well-crafted foreign policy of Beijing to earn permanent friends through lifetime development.

And it is also where India is failing to read the pitch. Instead of seeing China's BRI as a design to threaten its sovereignty, India should see it as an opportunity to help it by cashing in on China's enterprising skills. If India joins China's table, it will also benefit from the latter's dynamic initiative and it can reduce the tension which characterises the two countries' relation often.

Though seen from another angle, the competitive trade route spearheaded by India and Japan will help connecting regions more and integrating the world and reducing geopolitical tension. But the bottomline is: India needs to understand more the dealings in currency of trade, market and community-building – something the Chinese do wonderfully well without taking into notice differing political systems coming on the way of the BRI. That way, India can open a new avenue in its relations with China and find long-term solutions to the recurring tensions at the political level.