The Earth is, as of now, the only place in the universe where life has been found. Scientists, however, are yet to pinpoint exactly when life started and how it originated. In a quest to better understand life and its origins, palaeontologists from the University of Bristol have put together a simple timescale of all life on Earth. Everything from the first primitive life to the world as of now.

While that seems rather straightforward, actual fossil evidence of life on Earth is not as detailed, notes a release put out by the University. The closest researchers have got is the Archaean period—2.5 billion years ago—just when the crust of the Earth was cool enough to allow the continents to rise. By then, microbes were already present on the planet, says the report.

There are only a few fossils from the Archaean and even they generally cannot be without any doubt assigned to lineages that scientists are now familiar with, explained Holly Betts, lead author of this study. For example, the blue-green algae or the salt-loving archaebacteria that colour salt-marshes pink all around the world.

"The problem with the early fossil record of life is that it is so limited and difficult to interpret – careful reanalysis of the some of the very oldest fossils has shown them to be crystals, not fossils at all."

This is one of the reasons why fossil evidence that serves as records for the early history of life is fragmented. It is really difficult to evaluate, notes the report. This leads to new discoveries and reinterpretations of known fossils, which in turn, leads to a rapid increase in conflicting notions about the timescale of life on Earth.

Co-author Philip Donoghue, on the other hand, spoke of how fossils are not the only representation and evidence of life in the past. "The second record of life exists, preserved in the genomes of all living creatures."

Tom Williams, who is also involved in the study, explained that by combining fossil and genomic information, we can use an approach called the 'molecular clock'. This is loosely based on the idea that the number of differences in the genomes of two living species (say a human and a bacterium) is proportional to the time since they shared a common ancestor.

Using this method, the research team from Bristol and Mark Puttick of the University of Bath derived a timescale for all life on Earth that was not based on fossil evidence, rather than the molecular clock.

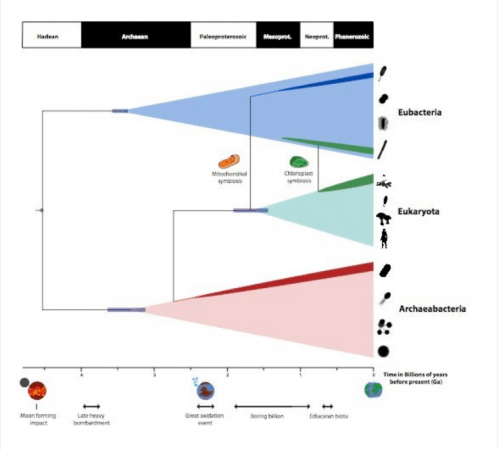

Using this approach, researchers were able to show that the Last Universal Common Ancestor for all cellular life- 'LUCA', existed early in the history of this planet. This puts it at 4.5 billion years ago—about the age of the planet itself, notes the report. This event is said to be not long after Earth collided with planet "Theia". It sterilised Earth and led to the creation of the Moon.

If this timescale was to be taken into consideration, then it is significantly earlier than the currently-accepted oldest fossil-based evidence, says the report. "Our results indicate that two "primary" lineages of life emerged from LUCA (the Eubacteria and the Archaebacteria), approximately one billion years after LUCA."

This result, says Davide Pisani, co-author of the study, is "testament to the power of genomic information, as it is impossible, based on the available fossil information, to discriminate between the oldest eubacterial and archaebacterial fossil remains."