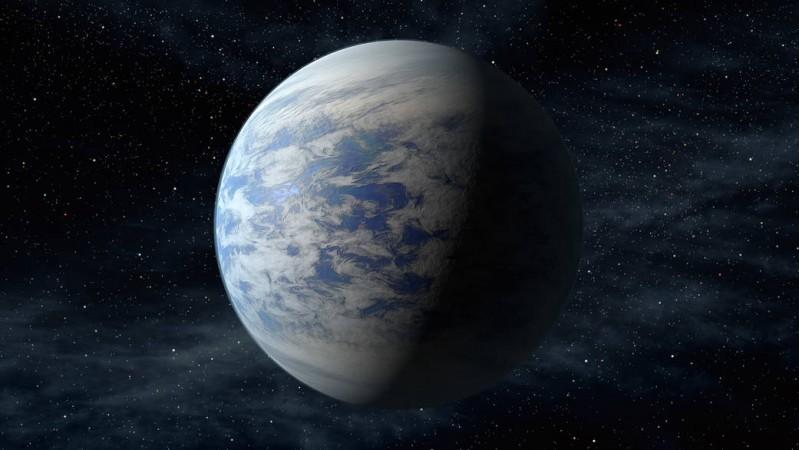

Astronomers now say that if a planet has a surface covered with water and there is no land, it still can host life. Till now, land was considered to be an important part of building life. Land offers the cycling of minerals, causes climates, and keeps a planet like Earth friendly for life.

Astronomers believe that this is not always the case. A new study has found that it is still possible for a planet to remain completely submerged, yet be in the right spot with the right climate to harbour and develop life. Such a planet can also stay habitable for much longer period than previously thought, say authors of this new study.

With new exoplanets being discovered in droves recently, there has been much debate about what makes a planet friendly for life. Liquid water is one -- only planets within the "Goldilocks Zone" of their stars were seen as prime candidates. Then, the debate shifted to climate -- scientists started to look for axial tilt. Recent developments pointed at exomoons of gas giants and some of them were found to be even more suitable for life than Earth itself.

"This really pushes back against the idea you need an Earth clone — that is, a planet with some land and a shallow ocean," said lead author Edwin Kite, a researcher at the University of Chicago.

Telescopes are getting better, NASA's TESS, for example, was built specifically to find exoplanets. As a result astronomers finding a lot more. Discoveries like this result in new research, notes a report by Sci-news, into life and how it could possibly develop and survive on other planets. Naturally, many exoplanets are vastly different from Earth. There are planets out in the universe that may be covered in water, not shallow like on Earth, but hundreds of kilometres deep.

One of the reasons why life was thought to need both land and water is because it needs a really long time to evolve. Light and heat from stars tend to change over extended periods -- sometimes billions of years. A planet that has both land and sea can maintain a stable climate over time. This is how Earth does it.

Researchers have simulated thousands of planets that were randomly generated, tracking their climate and how it evolves over billions of years. The surprise was that many of them stay stable for more than a billion years, just by luck of the draw, said Kite. "Our best guess is that it's on the order of 10% of them," he added.

Such planets sit in the right location around their stars, explained Kite. These planets just happened to have the right amount of carbon present, and they don't have too many minerals and elements from the crust dissolved in the oceans that would pull carbon out of the atmosphere. As for the amount of water, they have enough of it right from the beginning. Cycling carbon between the ocean and the atmosphere, they could maintain the right balance of concentration to actually maintain a stable climate, even without land.

"It does seem there is a way to keep a planet habitable long-term without the geochemical cycling we see on Earth," he said.