A new study undertaken by a group of researchers discovered that antibiotic-resistant infections can be treated with specifically targeted bacteriophages. When combined with antibiotics, certain bacteria-killing viruses aid in the fight against Mycobacterium abscessus, the bacteria that cause tuberculosis and leprosy.

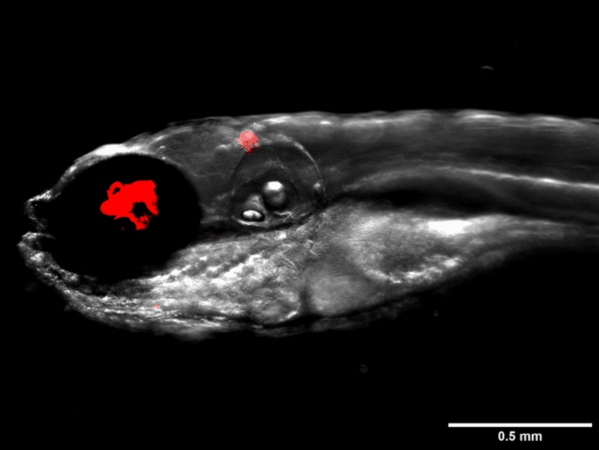

Laurent Kremer and his colleagues from the Université de Montpellier and the University of Pittsburgh conducted the study. Due to the extreme vulnerability of cystic fibrosis patients to M.abscessus, scientists opted to test their potential combination treatment on zebrafish, which have the key genetic mutation that causes cystic fibrosis in humans and closely resemble our immune system's reaction to bacterial infections.

The study conducted and its findings

They studied the zebrafish for 12 days following infection with M.abscessus. "Clinical trials are necessary, but there will be several more issues to address along the road, and zebrafish provide an excellent instrument for addressing these questions," says Graham Hatfull of the University of Pittsburgh. The researchers found that the fish got serious infections with M.abscessus and had a low survival rate of 20%.

Furthermore, the researchers examined how well sick fish recovered after being injected with Muddy, an antibacterial bacteriophage, and when Muddy was combined with an antibiotic called Rifabutin. They treated the infected fish for five days in both cases.

The results showed that when compared to being treated solely with the bacteriophage, the treatment with the antibiotic and Muddy resulted in significant improvement and less severe infections. With simply the Muddy, they had a 40% probability of survival, but with the combo, they had a 70% chance of survival.

A possible game-changer for covid

Recent research on COVID-19 patients found a strong association between secondary bacterial infections and poor outcomes and death despite antimicrobial therapy. Previously, heavy antibiotic use during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) pandemic increased the numbers of multidrug-resistant microorganisms.

Secondary bacterial infections in the lungs may contribute to the significant death rate found in the elderly caused to Covid-19. A reduction in the rate of bacterial development in the patient's respiratory system could gain time for the adaptive immune system to create specific antibodies.

Bacterial growth inhibition and the covalent binding of artificial antibodies to viruses should further reduce inflammatory fluid formation in the lungs of patients. Bacteriophages are capable of accomplishing these objectives.

The pace of bacterial growth could be slowed by aerosol application of organic bacteriophages that prey on the major types of bacteria proven to cause respiratory failure and should be completely harmless to the patient, said the study.