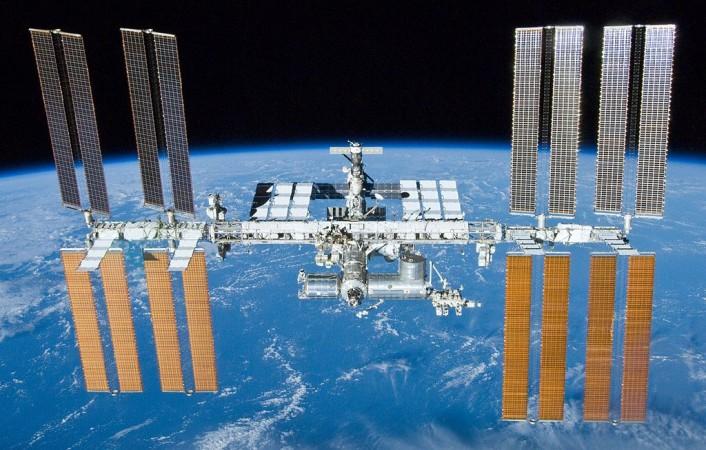

A new finding has been made regarding the survival of microbes on NASA's International Space Station (ISS). Bacterial cells which were treated using a common antibiotic were found changing their shape.

ALSO READ: Does Mars have a porous surface? Top things to know

This newly spotted phenomenon of the bacteria in near-weightlessness environments could cause a grave problem in medicating astronauts diagnosed with infections.

This finding was made by a group of researchers from the University of Colorado led by Dr Luis Zea.

E. coli bacteria were being experimented on in the near-zero gravity environment, which was found to "shapeshift" smartly and survive despite being subjected to antibiotic gentamicin sulphate in varying concentrations.

Read: NASA's Cassini is heading towards its Grand Finale on September 15: Top things to know

The drug antibiotic gentamicin is known for killing micro organisms on Earth.

When compared to a control group of the bacteria on Earth, the microbe portrayed a 13-fold rise in the cell numbers along with a reduction of 73 percent in the cell column size.

"We knew bacteria behave differently in space and that it takes higher concentrations of antibiotics to kill them," Dr Luis Zea stated.

"What's new is that we conducted a systematic analysis of the changing physical appearance of the bacteria during the experiments," he added.

ALSO READ: Rare phenomenon called 'earthquake lights' observed in Mexico skies! [VIDEO]

How bacteria functions in the near-weightlessness environments, which lacks gravity-driven forces such as buoyancy and sedimentation has been explained in a paper published in Frontiers in Microbiology.

According to Dr Zea, the ISS bacteria could ingest the drugs or nutrients through natural diffusion because the environment has no gravity-driven forces.The surface of the bacterial cell reduced in space and the molecule-cell interaction decreased too.

According to the researchers, this may impact how space farers with bacterial infections are treated.

Another finding made by the researchers was that the outer membrane and cell wall of the bacteria which comprises the bacterial cell wall had thickened in space and was shielding the bacteria from the antibiotic.

ALSO READ: NASA's SDO captures biggest solar flare of the decade: 7 things to know

Dr Zea also found that the microbe tended to form in clumps, which was a believed to be a defensive manoeuvre that could involve the outer cells protecting the inner cells from antibiotics.

Some microbes were even found producing membrane vesicles, which were small capsules formed outside the cell walls and acted as messengers to communicate with each-other, Dr Zea revealed.

On reaching a critical mass, these cells could synchronise to commence the infection process.

"Both the increase in cell envelope thickness and in the outer membrane vesicles may be indicative of drug resistance mechanisms being activated in the space flight samples," said Dr Zea.

"This experiment and others like it give us the opportunity to better understand how bacteria become resistant to antibiotics here on Earth," Dr Zea concluded.