So you already heard about driverless cars and automated forklift transporting packages of coffee pods at a Nestle plant in Switzerland. You also don't mind Google entering the race for home automation and Amazon helping its workers in the US to prepare for life after automation.

Now just to put things in perspective, you also remember Chris Cornell quavering in the 2006 Daniel Craig-starrer movie Casino Royale:

Arm yourself because no-one else here will save you

The odds will betray you

And I will replace you...

Are you able to connect the dots? We are just trying to assess how will automation transform the workplace and what will be its implications for employment.

This is what a McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) report has to say: Almost half of today's work activities in all sectors across the globe have the potential to be automated by 2055 and India and China together account for the largest technically automatable employment potential — more than 700 million full-time equivalents between them — because of the sheer size of their labour forces.

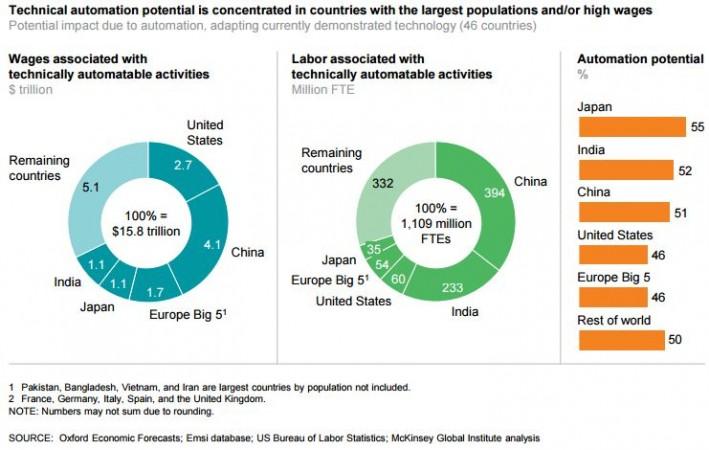

China, India, Japan, and the US account for just over half of the 1.1 billion technically automatable activities and $15.8 trillion in total wages. The potential is also large in Europe, where 54 million full-time employee equivalents and more than $1.7 trillion in wages are associated with technically automatable activities in the five largest economies — France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK.

Leading world bodies have differently projected what impact automation may have on job losses across the world. According to a Citibank with Frey and Osborne report, published in January 2016 using the World Bank data, risks are higher in India and China, where 69 percent and 77 percent, respectively, of jobs are susceptible to automation. In the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members, on average 57% of jobs are at risk.

A 2016 study of the World Economic Forum, automation and technological advancements could lead to a net employment impact of more than 5.1 million jobs lost to disruptive labour market changes between 2015–20, with a total loss of 7.1 million jobs in 15 major developed and emerging economies.

The MGI report, which estimates automation could raise productivity growth globally by 0.8 to 1.4 percent annually, anticipates that people displaced by automation will find other employment.

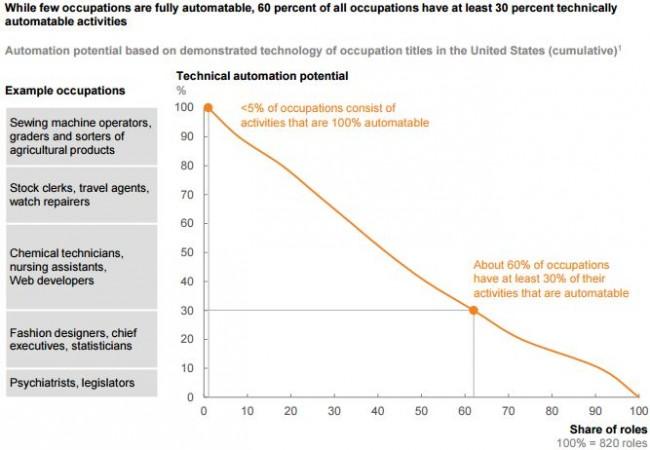

According to the MGI analysis of more than 2,000 work activities across 800 occupations, while less than 5 percent of all occupations can be automated entirely using demonstrated technologies, about 60 percent of all occupations have at least 30 percent of constituent activities that could be automated. However, automation could happen up to 20 years earlier or later than 2055 depending on various factors.

China and India have similar automation potential and dynamics, similar top sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing, retail, construction, and transportation and warehousing, and the automation potential within each sector is very similar. Manufacturing and retail play a larger role in China than India, whereas agriculture accounts for a significantly greater share of hours worked in India than in China.

Within sectors, India has more welders and sewing machine operators engaged in manufacturing production than China, and both of these job families have a higher automation potential than many other types of jobs, such as managing and developing people, and specialised expert technicians. At the same time, India has a lower proportion of jobs requiring interactions with stakeholders and managing and developing people, activities with low automation potential.

The largest impact on workers could be felt in labour-intensive sectors in China and India, whereas in other countries it will be felt across multiple sectors.

China and India both have very large farming sectors, with about 230 million people out of a working population of 450 million in India alone working in agriculture. In China, more than 200 million work on the land out of a total workforce exceeding 770 million. Given the employment size of this sector, even a relatively low rate of automation adoption of about 10 percent could have significant employment consequences in both countries.

In both China and India, the impact of automation on employment could also be felt in the retail and manufacturing sectors, as both have a relatively high potential for automation and a sizable labour force.

In the five major European countries, Japan, and the United States, the employment impact will likely be spread across multiple sectors, especially in the event that large-scale automation begins relatively soon.

On job creation front, workers in small businesses and self-employed occupations can benefit from higher income earning opportunities. The MGI report highlights that a new category of knowledge-enabled jobs will become possible as machines embed intelligence and knowledge that low-skill workers can access with a little training.

"In India, for example, Google is rolling out the internet Saathi (friends of the internet) program in

which rural women are trained to use the internet and then become local agents who provide services in their villages through internet-enabled devices. The services include working as local distributors for telecom products (phones, SIM cards, and data packs), field data collectors for research agencies, financial service agents, and para-technicians who help local people access government schemes and benefits through an internet-based device," the report notes.

Google's program aims to create more than 50,000 internet Saathis who will provide services to more than 50 million households in rural India.