On Friday (January 27), film-maker Sanjay Leela Bhansali was assaulted by a moral policing group on the sets of the film Padmavati. The director was accused of distorting the story of Padmini or Padmavati, the Rajput queen of the 14th century who had committed suicide to avoid humiliation in the hands of the approaching Muslim king of Delhi – Alauddin Khilji. Though experts say even this 'history' of suicide is actually fictitious.

The fringe group was reportedly angry with Bhansali for trying to show Padmavati and Khilji romancing in a dream sequence.

As is often seen today, social media also erupted, condemning the director for 'not honouring' the queen's dignity in the name of freedom of expression. The episode was found offensive by a section of the new generation of Indians who believe in majoritarian identities. In this case, it was Rani Padmini.

But what did those who took it as a national duty to save Padmini's 'grace' achieve through this?

The fringe elements found Bhansali and the film an easy target while the traders of hatred on social media hurled all kinds of indecent attacks on other members of the film fraternity.

In a nutshell, Bollywood was targeted as easy meat. Bashing celebs physically or verbally indeed gives one mileage in the public sphere.

What have these elements done on Rajasthan women's real woes?

The activists got cheap publicity, for sure. But did they actually bring any benefit to the women of Rajasthan? If people are so concerned over a woman who died over 700 years ago, are they equally worried over those who are alive and suffering today?

Rajasthan's alarming sex ratio

As per the 2011 Census data, Rajasthan has a sex ratio of 928 and child sex ratio of 888 (it has gone down compared to 2001 when it was 909), placing the state at a poor 23rd position among all states and Union Territories.

Besides, the state is infamous for child marriages (marriage of a woman younger than 20, the national average, as per the Sample Registration System or SRS baseline survey 2014), low rate of women's education, and low employment of women.

The SRS survey also said while the national average reproductive span is India is 6.6 years, Rajasthani women have a span of 9.2 years, lower by less than a year when compared to their counterparts in Uttar Pradesh, the state with India's longest reproductive span. Rajasthan has the second highest percentage (38) of households having six or more members.

High maternal mortality rate (MMR)

Rajasthan also fares poorly on the MMR charts as well. While UP has the worst figure of 27.6, Rajasthan is second with 23.9, revealed the Sample Registration Survey of 2014.

The percentage of unemployed Rajasthani women is very high

Also, in the state, which currently has a woman chief minister — Vasundhara Raje — a 2011 Census data released in July 2014 revealed that 73% of women in the age group of 15-59 were unemployed (only 52 lakh out of almost 2 crore women in the age group in the desert state have a job).

Very few women are breadwinners for their families

The figures also show that only 30% women in the age group of 20-39 – the most productive age group – are earning money to support their families. Yet another sorry picture is that while 11 lakh women in the state were seeking jobs, they were failing to land any, or were being stopped by a patriarchal society.

The high rate of urban unemployment among the women of Rajasthan also gives a hint that they were not being allowed to migrate for work to other states.

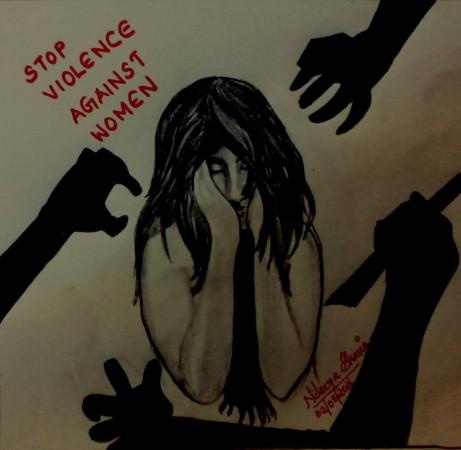

High instances of rape in Rajasthan

Figures released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) in 2015 showed Rajasthan ranked the top three in terms of rape cases that year (3,700 plus).

Also as per the NCRB, Rajasthan is among the top five states of the country in terms of crimes aagainst women. While in 2005, the number of cases of crime against women in that state was 11,657, in 2014, that figure went up to 31,151.

It is much more convenient to ignore the real issues

One doesn't know whether the fringe element activists or the tech-savvy Twitterati keep enough track of the reality in which women of Rajasthan live.

There is a slim chance they do because dealing with serious issues requires a lot of hard work, without an easy guaranteed solution in sight.

Attacking a Bhansali or a Karan Johar over his sexual orientation is a much easier thing to do, since it gives instant publicity that many of us yearn for.

In these days of deep polarisation where you are either a nation's servant or a Quisling, the prizes for practising majoritarianism are even higher. One suspects the anger vented on the Padmini issue was more intense since it involved a Muslim king, even if he ruled parts of this country.

By the way, did those who manhandle Bhansali praise the makers of Parched for provoking a thought in us?

Our priorities are misplaced because we perhaps know that the solutions to these problems are beyond our reach. The latest trend of worshipping cultural symbols (Shivaji, Rana Pratap and now Rani Padmini) to establish a brute majoritarianism in public life is a sinister project for the idea of India.

We cannot keep looking at the past to bury our future. The time bomb is ticking.