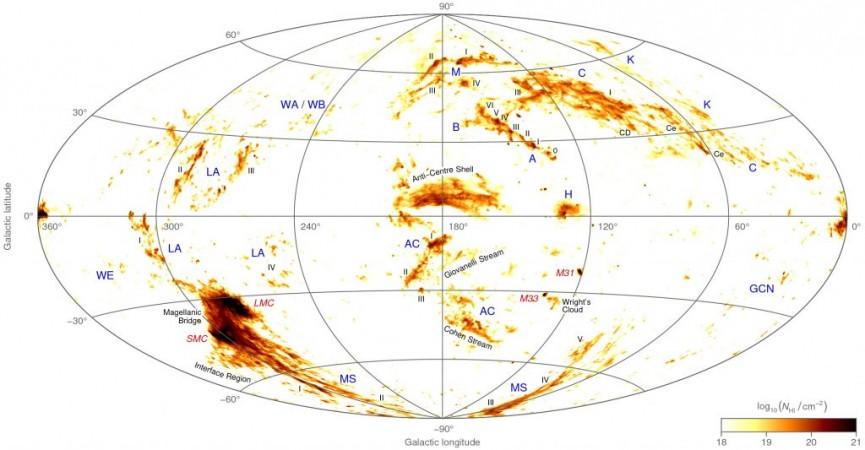

As much as 13 per cent of the sky is covered by high-velocity clouds of gas moving at a fast pace, says an Australian scientist who created a very detailed map showing it.

The detailed map shows that the entire sky is covered with curious clouds of neutral hydrogen gas which moves at a different pace compared to the normal rotation of the Milky Way.

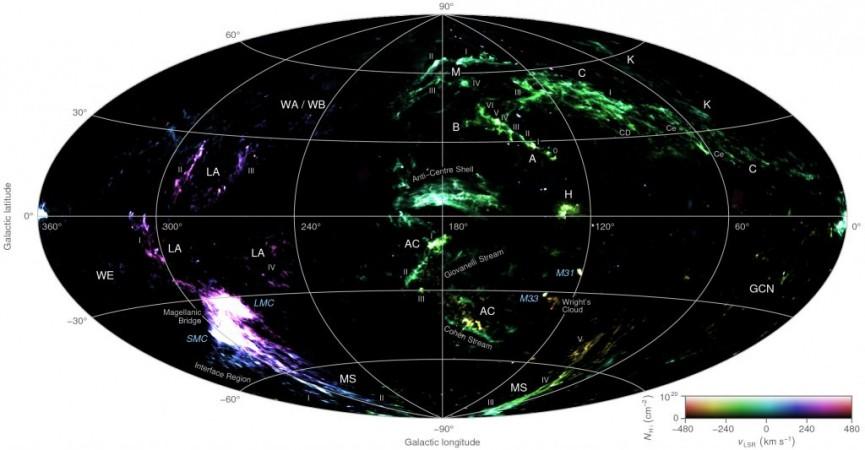

According to Dr Tobias Westmeier, from The University of Western Australia, who created the map, these gas clouds are moving towards or away from us at speeds of up to a few hundred kilometres per second.

"They are clearly separate objects," he added.

Dr Westmeier created the map by taking the picture of the sky and masking out the gas moving at the same speed as the Milky Way to show the location of the gas travelling at varying speeds.

It helped in creating the first ever most sensitive and high resolution all-sky map of high-velocity clouds.

The map portrays gas in stunning detail and also portrays the filaments, branches and clumps within the clouds for the first time.

"Starting to see all that structure within these high-velocity clouds is very exciting," Dr Westmeier said.

"It's something that wasn't really visible in the past, and it could provide new clues about the origin of these clouds and the physical conditions within them," he added.

Data from a study of the entire sky dubbed HI4PI, which was released last year was utilised in this study. Observations from CSIRO's Parkes Observatory in Australia and the Effelsberg 100m Radio Telescope operated by the Max-Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany was combined in the survey.

Various theories regarding where the high-velocity clouds come from were formulated by the astronomers.

"We know for certain the origin of one of the long trails of gas, known as the Magellanic Stream, because it seems to be connected to the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. But all the rest, the origin is unknown," Dr Westmeier said.

"Until about a decade ago, even the distances to high-velocity clouds had been a mystery. We now know that the clouds are very close to the Milky Way, within about 30,000 light years of the disc," Dr Westmeier said.

"That means it's likely to either be gas that is falling into the Milky Way or outflows from the Milky Way itself. For example, if there is star formation or a supernova explosion it could push gas high above the disc," he explained.

Astronomers across the world will have free access to the map; it would aid the researchers in learning more about high-velocity clouds as well as the local Universe.