No history curriculum is complete without classes recounting the horrors of the Black Death that wiped out massive populations across Europe in the mid-1300s.

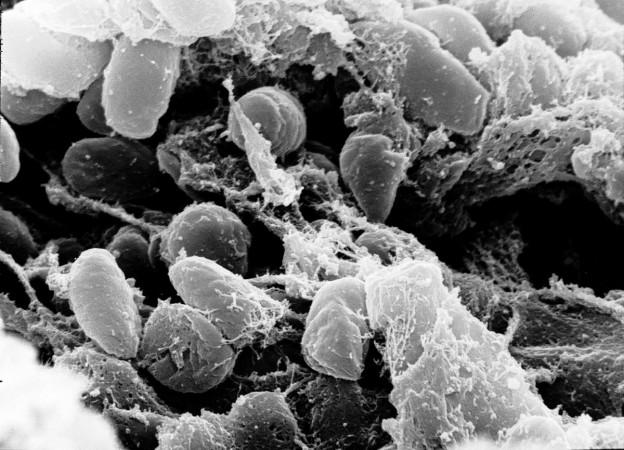

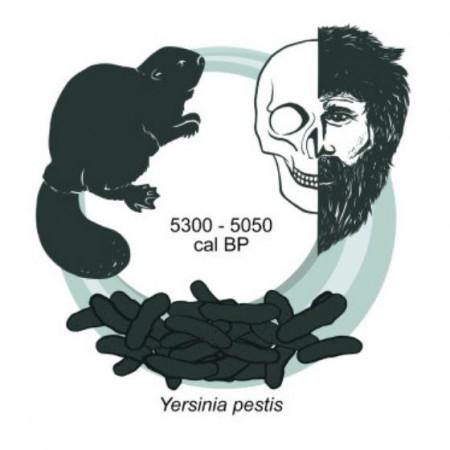

The plague—which is often considered the worst pandemic in human history—was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium carried by flea-laden rodents. Now, scientists have found evidence of a much older strain of the pathogen in the remains of a 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer from Latvia.

According to the new study, genetic analysis of the remains christened 'RV 2039' revealed that this ancient strain of Y. pestis was likely less infectious and not as lethal as its form that ravaged medieval Europe. The research found that the disease probably spread directly from infected rodents and did not require fleas for its transmission.

"What's most astonishing is that we can push back the appearance of Y. pestis 2,000 years farther than previously published studies suggested. It seems that we are really close to the origin of the bacteria," said Dr. Ben Krause-Kyora, senior author of the study, in a statement. The study was published in the journal Cell Reports.

Killer of the Masses

Y. pestis causes a lethal disease broadly known as plague. Flea-carrying rodents act as its vector. The disease is transmitted when fleas infected with the bacteria bite human beings. Sometimes, the disease can be passed on to human beings via the handling of an infected animal.

Plague occurs in three forms: Pneumonic plague (acute infection of the lungs); Septicemic plague (infection of the blood); and Bubonic plague (flu-like symptoms along with painful swelling of lymph nodes under the skin called 'buboes').

While different forms of plague intermittently ravaged different parts of the world over the course of centuries, the bubonic plague pandemic in the 14th century is considered the worst. It swept across Asia, Africa, and Europe, and ravaged Europe to the point where nearly 75 percent of the populations of several cities succumbed to the disease.

Nearly all the victims developed painful and disfiguring buboes filled with pus. Bubonic plague can now be effectively treated using modern antibiotics. However, the disease has a mortality rate of up to 90 percent if left untreated.

The strain of Y. pestis examined in the current study was acquired from the remains of a 20- to 30-year-old hunter-gatherer carrying the plague. Dated to be around 5,000-years-old, the skeletons of 'RV 2039' and a 12 to 18-year-old woman (RV 1852) were excavated in the region of Rinnukalns (in present-day Latvia) in the late 1800s.

However, after 'vanishing' for over a century, the remains were re-discovered in 2011; in the collection of German anthropologist Rudolph Virchow. Since then, two more burials have been discovered at the primary site—suggesting that they probably belonged to the same group of hunter-fisher-gatherers.

Lacking A Crucial Gene

For the study, the authors analyzed samples from the bones and teeth of all four hunter-gatherers. They sequenced their genomes and examined them for viral and bacterial pathogens. Interestingly, evidence of Y. pestis was found only in RV 2039. The team then reconstructed the bacterial genome and compared it to other known earliest strains of the pathogen.

Astonishingly, the team learnt that this strain of the bacterium was in fact the oldest ever to be discovered. It probably belonged to a lineage that arose around 7,000 years ago; only a few centuries after Y. pestis diverged from its precursor, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis.

Importantly, the ancient strain lacked a vital gene that enabled fleas to act as vectors spreading the plague. This particular gene played a crucial role in the effective transmission of Y. pestis to human hosts during the medieval bubonic plague. Also, the death of the human host was required for flea-based transmission. This means that the emergence of this specific gene may have triggered its transformation into a more potent disease.

"What's so surprising is that we see already in this early strain more or less the complete genetic set of Y. pestis, and only a few genes are lacking. But even a small shift in genetic settings can have a dramatic influence on virulence," expressed Dr. Krause-Kyora.

The study also suggested that it may have taken over a thousand years after RV 2039 for Y. pestis to develop all the mutations that primed it for flea-based transmission. However, the level at which the 5000-year-old human ancestor experienced the effects of the disease is uncertain.

Slow-Moving and Less Contagious

The team believes that it is very likely that RV 2039 died due to the Y. pestis infection. This is because the pathogen was found in his bloodstream. However, they stated that the progression of the disease may have been considerably slower. The scientists also noted that the concentration of the bacteria in his bloodstream was very high.

In older rodent studies, an elevated load of Y. pestis has been linked to infections of lower severity. Moreover, the people buried in RV 2039's grave were not infected. This, according to the researchers, suggest that the plague was most likely not a highly contagious respiratory form.

It is also possible that this ancient strain was transmitted directly to human beings through the bite of an infected rodent, and the disease was confined to the infected individual.

"Isolated cases of transmission from animals to people could explain the different social environments where these ancient diseased humans are discovered. We see it in societies that are herders in the steppe, hunter-gatherers who are fishing, and in farmer communities--totally different social settings but always spontaneous occurrence of Y. pestis cases," explained Dr. Krause-Kyora.

Challenging Theories of Population Decline

The findings of the study—the ancient version of Y. pestis was probably a slow-spreading disease and had limited transmissibility—question several theories about the growth of human civilizations in Asia and Europe.

Many historians have posited that contagious diseases such as like Y. pestis metamorphosed largely in 'megacities' with a population of over 10,000 people situated near the Black Sea. However, the age of RV 2039's strain—5,000 years—predates the formation of such big cities. Rather, agricultural activities were only beginning to appear and the populations were much scarcer in Central Europe.

In combination with the timeline, the less aggressive and fatal nature of this Y. pestis strain also challenges the conjectures that the pathogen led to a sharp decline of populations in Western Europe at the closing of the Neolithic Age. The team asserts that a close examination of the history of Y. pestis may help reveal more about the genomic history of human beings.

"We know Y. pestis most likely killed half of the European population in a short time frame, so it should have a big impact on the human genome. But even before that, we see major turnover in our immune genes at the end of the Neolithic Age, and it could be that we were seeing a significant change in the pathogen landscape at that time as well," concluded Dr. Krause-Kyora.

!['Had denied Housefull franchise as they wanted me to wear a bikini': Tia Bajpai on turning down bold scripts [Exclusive]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806605/had-denied-housefull-franchise-they-wanted-me-wear-bikini-tia-bajpai-turning-down-bold.png?w=220&h=138)

![Nayanthara and Dhanush ignore each other as they attend wedding amid feud over Nayanthara's Netflix documentary row [Watch]](https://data1.ibtimes.co.in/en/full/806599/nayanthara-dhanush-ignore-each-other-they-attend-wedding-amid-feud-over-nayantharas-netflix.jpg?w=220&h=138)